When objects are more than a prop: Antonino Giuffré reflects on the secret life of the silent stars of the show

Standing here long before beginners’ call, I watch the audience enter and murmur rather awkwardly.

They sit, they chat. Some of them look at me – just a glance most of the time, while some of them stare at me intensely making me wonder what’s really going on in their brains.

I wait.

I like being observed.

I love to make them wonder what’s going to happen.

Will I move? Will I be moved?

Maybe I will just sit quietly for the whole length of the play.

I love to grasp a pinch of the anticipation they are breathing in this very moment.

And in the meantime, I stand.

Tall and firm.

That’s my assigned role right now as per director’s notes:

A coat-stand, stage left, stands tall and firm.

I stand, and I wait.

I like being observed. It’s my favourite part of the show.

Little do they know of what will happen in the next hour or so: How many times will I be used, moved and manhandled? When will I be offering support to tired actors or protect them from their deepest shame? Not an easy job, trust me on that, especially with the few notes I’m given in the script:

A cautiously adjusts his immaculate coat on the coat stand.

B grabs the coat-stand and tries a lascivious tango move in a desperate attempt to cover his naked precious jewels.

Tiny details you say, but incredibly important in my journey.

I do what I can, but really, some of my colleagues often seem to overlook these little bits of life that a prop like me creates on a stage. That we all create together.

Because like me, any other object is alive as much as anyone else on stage.

We are part of the performance, although not credited, and we contribute to it as much as any other part of the mechanism we bring on stage.

And in the meantime, I stand.

Tall and firm, as per director’s notes.

I am a professional.

And so we all are, us theatremakers, desperately building our shows around plotlines, characters, emotions, concepts and ideals. In a human-centred world we write stories with us as the main focus, so often failing to acknowledge what’s around us.

Other Humans. Four walls. A floor. Air. Breath.

And objects.

This is the journey that I have personally undertaken in my practice and I wish to pursue: a theatre that can reflect the new centrality that objects have taken in our lives and a research for a more mature and aware relation between performers and their props.

From the study of outdoor theatre and its focus in the manipulation of big objects, passing through clown performances where delicacy and precision in handling even the tiniest of props (when visible or even present) the object has always been at the centre of my art. Marionettes and hand puppets have been more than once a means for transmitting the widest variety of human emotions, and where I couldn’t find an object that would suit my artistic purpose I have built it, in constant research to break the stillness of a traditional stage.

In Victor Egò, the first piece I devised and directed, I brought on stage a monumental dinner table that could be transformed with a swift movement to a hand-puppet theatre, creating a stage within a stage, overlapping two fictional worlds and styles. Further research in this direction was my second piece, The things we have in common (for Nikalos Teatro). Linchpin of the story was a hoarder that had his prized material possessions come alive as his only friends. This allowed me to research the voice and personality of different objects, as well as the possibilities of interactions between humans and objects leading to incredibly moving shards of ‘humanity’ between a radiator and its owner.

And then, the circus came into my life.

Not much to invent there: the props were already there and they were already essential to the show. But again, how?

Contemporary circus artists have been asking themselves this question for decades now.

They have explored, theorised and practised in almost every possible way their relationships with their apparatus and how to interact with them. Their approach to circus props is immensely fascinating: it can show a variety of colours that sometimes resembles a human relationship, and can go way beyond. Their apparatus can be extensions of their bodies as much as an impediment, their only link to safety, and their voices. The pieces of apparatus are not just there: they are as much a part of the performance as the bodies on stage.

But why are they there? Why is the trapeze hanging in front of the stage as naturally as the cheeky coat-stand of a farce?

It’s the norm: an agreement between audience and performers, a disruption of reality accepted by both parties, a new reality where we as audience must accept the existence of a trapeze as normal fact of life; in a kitchen maybe, just as much as we accept the stubbornness of the cat persistently trying to push a glass off of a table.

Inexplicable, both of them, yet fascinating.

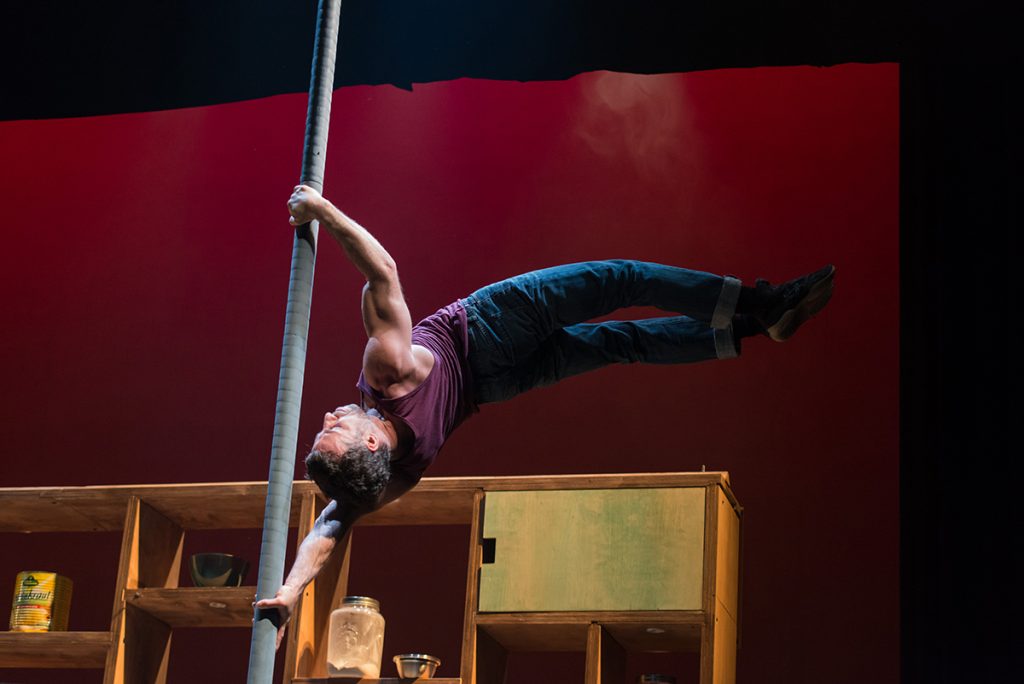

And before we even start questioning it, we may find ourselves immersed in the world of the Argentinian desaparecidos, while an artist moves seamlessly up, down and around the pole like in Cuisine and Confessions from Montreal-based company Les Sept Doigts (7 Fingers), one of the very first contemporary circus shows I have witnessed. And his last suicidal fall into the darkness speaks volumes about the open wound that sad page of history has left.

But immediately, the appearance of a piece of apparatus and its interaction with the space around it creates another world – a jump into a new journey that we always hope our audience is happy to engage in. It can be magical as much as it can be limiting.

The presence of the rigging creates a world of expectation that must be used with craft and delicacy. Is this expectation a curse for my piece, my art and everything I do to abstractness and conceptual art; or can we engage in a journey where we can forget even for a split second about the tangible physicality of the rigging?

What would happen if a simple banana gets elevated as the star of a show where every household object is purposely and thoughtfully set to spark a dramatic (and acrobatic) action, just like in The Hogwallops from Lost in Translation Circus.

The risk is that we might end up so drawn into this world that an aerial act performed on a zimmer frame looks like the inevitable resolution to a family feud.

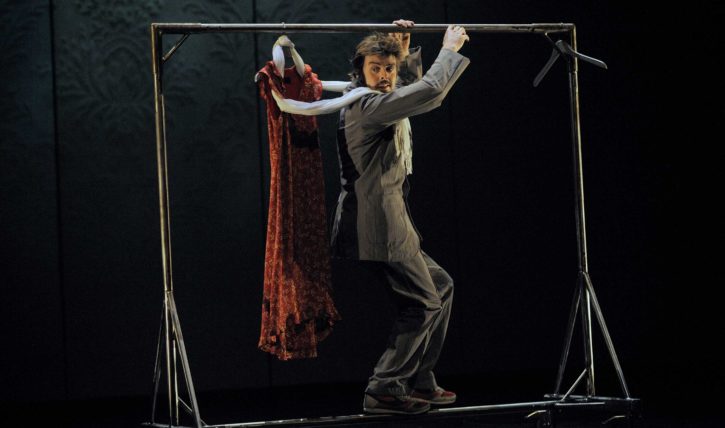

And sometimes a coat rack and its clothes come alive quite literally, and we could witness bits of magic suspended between circus and object animation, las happens in one of the highlights of Cirkopolis by Cirque Eloise.

But what about the rigging, the ropes, the poles or even the walls on a stage?

Could we let them breathe and live as much as we do, at least for the short duration of a play?

Those are the questions that have been driving my work as an artist in these last years.

The same questions that I have asked the performers, directors, set designers and all the other creatives I have worked with.

Am I really looking for answers? Not really. It’s the journey that matters

And in the meantime, I stand.

Tall and firm.

Antonino Giuffré studied drama in Italy, where he created/directed numerous physical theatre shows; then developed his practice in the contemporary circus world – writing, producing and performing with the UK-based company Lost in Translation Circus. Ninno took part in the Total Theatre Artists as Writers programme 2020.

https://www.lostintranslationcircus.com/ @ninno87

Featured image (top): Nikalos Teatro: The things we have in common. Photo by Ana Kusch.