Dorothy Max Prior speaks to Alexander Vantournhout and Bauke Lievens about the creation of ANECKXANDER: ‘a tragic autobiography of the body’.

Is it circus? Is it dance? Is it performance art? Clown, even? ANECKXANDER, which comes to Jacksons Lane 22–24 January as part of the London International Mime Festival 2016, is all and none of the above. It is a collaboration between two extraordinary Flemish artists, performer Alexander Vantournhout and dramaturg Bauke Lievens, who tussle with the questions of what defines an artform, and how you can explore the gaps in between those definitions. Lest this all sounds rather cerebral, rest assured that their work together is totally embodied – physical, visual, visceral performance.

Bauke Lievens – who started work on this piece as dramaturg, but soon found herself in at the deep end as co-author and director – has a formidable reputation, having worked previously as dramaturg with Les Ballets C de la B, and Un Loup pour l’Homme, amongst many others.

Alexander Vantournhout is just 26 years old, yet already has an enviable track-record in contemporary circus. After graduating from ESAC circus school in Belgium, with Cyr wheel (a large single wheel that the performer spins in and around across the floor) as his specialty, he created his first show Caprices (2014), which was very favourably received. But this is only part of the story: he is also a graduate of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s PARTS school, so is also a seasoned dance-theatre performer.

Alexander Vantournhout. Photo Bart Grietens

ANECKXANDER is the first collaboration between the two artists, and it has proved to be a fruitful one. An early work-in-progress version of the piece won the prestigious CircusNext competition in late 2014. They then took what was a 20-minute piece and worked together to extend it into a full-length piece, which has been shown around 25 or 30 times throughout 2015, travelling from homeland Belgium to Holland, France, Italy, Slovenia, and Croatia.

So acclaim in the contemporary circus world is theirs – but the question of whether or not they belong in that world is core to their artistic investigation together. Key to the resolution of that question would be to define the thing they are conforming to or rebelling against. So, what in their view, is circus? ‘A question we ask of ourselves all the time’ says Bauke.

Circus, Alexander believes, is ‘dance plus several specificities’, and it is in essence about the human body’s relationship to objects. ‘There is no circus without objects,’ he says, dismissing acrobatics and acrobalance as ‘not circus’ – although he adds with a grin that he feels that ANECKXANDER is also ‘not really circus’. (Shhh – don’t tell the CircusNext judges!) At another point in our conversation, he offers another definition of circus, inspired by Peggy Phelan’s views on the nature of performance art: ‘She talks of performance closing the gap between the real and the representation – perhaps the same could be said of circus’.

Circus, in his experience anyway, is essentially a solo endeavour – the person and their equipment – whereas dance, or dance-theatre at least, is in essence collaborative. (I think about asking where flying trapeze fits into this theory, but I resist.) It is very true, we agree, that physical objects play an important role in circus, contemporary or traditional. Alexander may have abandoned his wheel in ANECKXANDER, but there are objects a-plenty in the piece. Boxing gloves and platform boots, for example.

Alexander Vantournhout in ANECKXANDER. Photo Bart Grietens

In discussing the objects used in the show, Bauke talks about her interest in prosthetic limbs; and how the use of the chosen objects (the cumbersome gloves and boots) become something resembling prosthetic objects that both enable and inhibit the body’s movement. It is exactly this balance between restriction and expansion offered by the objects that interests her. Also, as Alexander is otherwise naked in the performance the objects both ‘compensate for and accentuate’ the vulnerability of the body. ‘We are trying to re-define objects,’ he says.

For Alexander’s part, he talks about the early stages of the work where his movement research centred around observing and measuring his own body: someone had once told him that his neck was rather long, so he set out to objectively observe his own physical form. His neck might be longer than average, but his legs are shorter – hence the decision to explore the donning of platform shoes to both ‘compensate and accentuate the vulnerability’. It was either that or high heels…

A more conventional circus performer might have settled for stilts, which similarly enhance and inhibit the movement of the legs, although of course in rather different ways – but Alexander is insistent that he ‘didn’t want to use traditional existing circus disciplines,’ instead choosing to bring a circus-informed approach to the exploration of ‘ready-mades’ and ‘entering the domain of a new language’. He says that his work is ‘non referential’ to other artists’ work, but is ‘self referential’ and ‘hard to situate within one artform’. We talk a little about the different ways that objects are used in performance, and how the same object – a stick, say – might be used by a juggler, a puppeteer, or a performance artist. Which brings us onto the topic of the real versus the representational: at the heart of theatre lies illusion; whereas circus, dance and performance art trade in the real. Bauke declares that ‘the circus object makes the body of the performer into an object’ and that conventionally in circus the chosen object becomes a tool to elevate the capacity of the human into the realms of the super-human ‘who is often seen as a freak’. Take away that tool and what do you have? ‘It is like Iron Man, worthless without his suit!’ Ultimately, the interest here is in ‘the person behind the tricks’.

So Bauke and Alexander are keen to explore what happens when you take away the safety net, so to speak, of the familiar circus object: the prop that holds you up (be it wheel or hoop or ball or rope). In ANECKXANDER, there is an interest in exploring the ‘handicap’ that these alternative objects offer – chosen for their functionality rather than for any meaning that they offer.

We talk a little at this point about the role of the dramaturg in the creative process – although both are quick to point out that Bauke quickly ‘lost her role as dramaturg’ in the making of ANECKXANDER as she become more and more involved, so is now a full-blown creative collaborator and co-author of the piece.

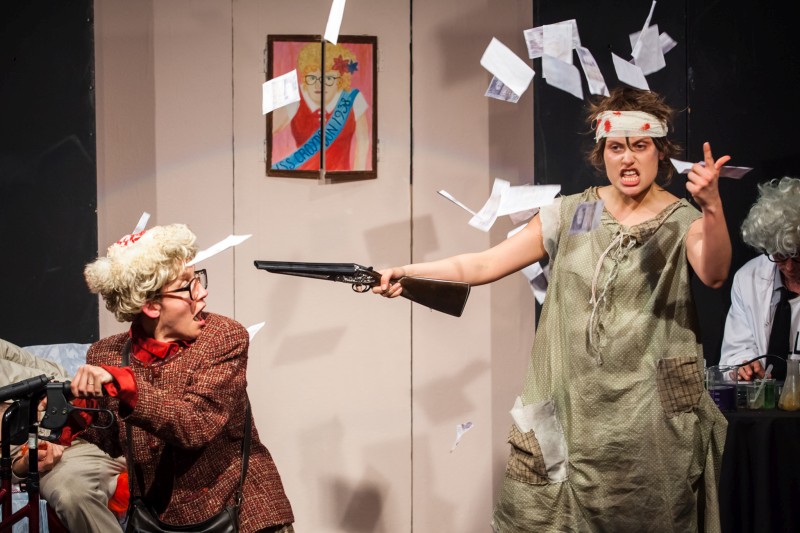

ANECKXANDER. Photo Bart Grietens

Another point of discussion is the subtitle of ANECKXANDER: ‘a tragic autobiography of the body’. The ‘autobiography of the body’ part is clear enough, having already learnt that the beginning of the process for the show was the detailed exploration of the measure of Alexander’s physical self and own ‘body proportions’. But what of the ‘tragic’?

‘Circus is a very tragic business,’ says Bauke, going on to give another definition of circus, which she sees as ‘ the promise of, and escape from, tragedy’. Yes, that makes sense to me: every time we see someone soaring above us, we know it could all go horribly wrong at any moment. This is not acting – this is for real. And every circus performer (and dancer too of course) is in a constant battle against age, infirmity, injury. She also talks of the tragedy of circus in terms of it as a form in which the artist is ‘reaching for a goal that always displaces itself’.

Alexander voices an interest in the relationship between the comic and the tragic, citing the writings on laughter by French philosopher Henri Bergson, and his view that if the tragic is repeated and repeated, it becomes comic (something well known amongst the clown community). He talks of the well-documented link between laughter and the release of tension; and the relationship between laughter and discomfort: ‘that’s really what happens in the performance…’ So Aneckxander, in its investigation of the tragic, is drawn almost inevitably towards the comic.

Another interesting aspect of the piece is its use of music – a composition by Arvo Part (a piano piece called Variations for the Healing of Arinushka) that is played on a keyboard onstage (by Alexander), then looped, and deconstructed – the left hand and right hand playing the same melody slightly out of synch. ‘The choreography is written precisely to this’ says Alexander, and he talks of how the music can create the story. Narrative is important to the work, says Bauke, although it is not a conventional linear narrative – and music provides a ‘tool’ for creating a narrative, an arc that takes us through the performance. Part of her role in the creation of the work was to help to build an ‘evolution’ between one movement and another.

Like many contemporary practitioners, both Alexander and Bauke express a desire to explore ‘presence’. Bauke talks of wanting a presence that makes the process clear, and shows the transition from one form to the next, rather than ‘presenting a series of acts,’ and of making visible the mechanisms of the performance, ‘to show that the performer is human, not superhuman’. They also talk of the specific situation of working in Flanders, which has a very vibrant and progressive theatre community in which definitions of theatre are perhaps a little different to those in the UK. ‘What we call theatre you might call performance,’ she says. Bauke speaks of perhaps being part of a theatre practice that is ’making palpable the gap between personage and performer,’ as opposed to conventional acting.

Ultimately, what they are both interested in is creating work that is very clearly ‘made by people not machines,’ noting that much high-level contemporary circus is missing the humanity. ‘Beautiful machines – but machines,’ says Bauke of Cirque du Soleil…

When I speak to them, Alexander and Bauke are in rehearsal, tweaking ANECKXANDER for its UK debut at the London International Mime Festival. They are also about to enter the research phase for the next show together – in which even the objects will be discarded, leaving just the body as object to play with. It will be a duet, and the second performer will be playing a dead body. The possibilities for both comedy and tragedy are endless…

ANECKXANDER is presented at Jacksons Lane 22–24 January 2016, as part of the London International Mime Festival. Book at www.mimelondon.com

Post-show discussion on Saturday 23 January, facilitated by Dorothy Max Prior.

For more on the work of Alexander Vantournhout and Bauke Lievens, see http://alexandervantournhout.be/

ANECKXANDER was created as part of Bauke Lievens’ 4-year research project, Between Being and Imagining (KASK, Ghent). Other aspects of the research will include masterclasses, writings which will be edited in their English version by Sideshow Circus Magazine’s John Ellingsworth, and a series of ‘encounters’, which comprise three days of structured conversations in different formats, the first in Ghent in 2016 and then subsequently in Bristol in the UK and in other European cities, 2016-2017.