Mind, body, spirit. Thomas Wilson reflects on the closing weekend of SPILL 2015

SPILL Festival has, over the past decade, gone from strength to strength, firmly establishing itself as one of the key London arts festivals, programming adventurous and rigorous work from established and new artists, across a number of venues – which for the 2015 edition included the Barbican, National Theatre/ NT Studios, Toynbee Studios, Hackney Showroom, and numerous off-site and public spaces. The established artists category this year included two pieces by veteran US performance artist Karen Finley, Written in Sand (live performance) and Ribbon Gate (installation), both responding to the subject of AIDS. Finley’s inclusion is a marker of the ways in which SPILL founder Robert Pacitti has championed work that directly addresses lived experiences, and also clearly embodies SPILL 2015’s theme On Spirit – defined by the festival as: ‘From the Latin spiritus meaning breath, Also: soul, courage, and vigour.’

This theme was also embodied in the work of the younger generation of artists, such as FL Alexander’s No Where // Now Here; Daniel Oliver’s Weird Séance, and the headline-grabbing Site by UK artist Poppy Jackson. Jackson’s actionist work, in which she installed herself, naked, on the roof of Toynbee Studios, sought to question the place of the female body in space and as a space. The widespread coverage in the tabloid press, and the articulate defence by Lyn Gardner in The Guardian, and by the artist herself on London Live TV, is a clear marker of how the work that SPILL presents is often the start of difficult and necessary conversations about art in contemporary society.

FK Alexander: No Where // Now Here. Photo by Holly Revell / DARC for SPILL

Elsewhere at SPILL 2015, Zierle & Carter created three different site-responsive works (in the masonic temple at the Andaz Hotel, Liverpool Street; in the tropical plant conservatory at the Barbican; and outdoors at the National Theatre) investigating ‘the shapeshifting qualities and gifts of three different totems… Swan, Moth and Horse’; Kris Canavan enacted a processional, psychogeographical ‘aktion’ in public space, Dredge; and Robin Deacon’s White Balance: a History of Video investigated the truth of autobiographical material, telling a series of stories on ‘time-travel, haunting and hallucination’ armed with a number of vintage video cameras and players. The packed two-week programme also included SPILL Think Tank Salon talks, live experimental music events (including a show by cult hero Othon), and a showcase of work by emerging artists presented at the National Theatre Studio.

In the final weekend, Toynbee Studios continued to play host to the installation In My Room (Dorothy Max Prior), which explored punk, porn and popular culture in the 1970s; and a one-on-one performance about memory, Recall, by Ria Hartley (both reviewed here in Rebecca Nice’s first-weekend Toynbee round-up). In addition, there were two further works: The elegiac double-diptych of films La Salle d’Attente by Pacitti and George Stamos; and Lauren Jane Williams’ viscerally fleshy performance-cum-sculpture Here is Not the Place for Nostalgia….

Pacitti and Stamos’s two films both take their content from encounters with ‘legendary author, raconteur and professional homosexual’ Quentin Crisp; using film footage of these meetings to open-up the nature of the relationship between gay men of different generations.

Pacitti’s film, played on two parallel monitors, was shot on black-and-white Super 8 in 1996. It follows Crisp (who was 88 at the time) and Pacitti (28) as they take a walk through New York City. The soundtrack for the film, listened to on headphones, is Nico’s Chelsea Girls. This 1967 song tells the stories of some of the residents of NYC’s famous bohemian Chelsea Hotel. Released in the same year that Pacitti was born and that homosexuality was decriminalised in the UK for men over 21, the track provides a sense of the context of the meeting of Crisp and Pacitti.

The distinctive figure of the elegantly dressed Crisp, accompanied by the towering and more soberly dressed Pacitti, lies in stark contrast to the graffiti-covered streets and vans of Manhattan. The camera shifts between capturing the two men’s conversations and scanning the various buildings they pass – mostly prosaic fast-food joints, or shuttered shops, but also famous art organisations (Cooper Studios and Tisch School of Arts). A subtle sense of historical context echoes in these tracings of landscape, though it is the gentle dynamic of the two figures that sits at the heart of the work. It is clear that Pacitti’s meetings with Crisp are a fundamental part of Pacitti’s make-up as an artist, but this film has a homely quality that erodes the notion of the inspiring figure and his trans-atlantic acolyte. Instead there is the simple human act of two men taking a walk. Although not present in the work, it’s hard, knowing of Pacitti’s work, not to connect this to they way he has sought to create a similar open, conversational relationship between emerging artists and their more established forebears during the various SPILL Festivals of the past decade.

Quentin Crisp and George Stamos in The Waiting Room

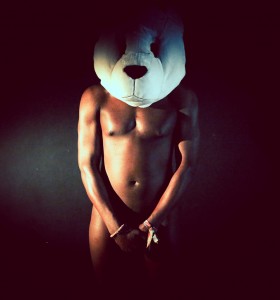

Visually, Stamos’s part of the work, also a diptych of films, strikes a notable contrast. Projected onto two large screens set at an oblique angle to one another, the film has a rich but faded colour to it. One screen sets Crisp in the mid-ground, seated in a plush high-back chair in front of the bottom part of a neo-classical painting. In the foreground, a lemon-yellow chaise-langue, on which a naked Stamos ‘dances’ for Crisp’s pleasure. An ex-go go dancer, Stamos’ movements are sinuous as he shifts position, writhing and twisitng on the chaise-langue, his naked form drawing Crisp’s knowing gaze. At points the film stutters back and forth, replaying brief moments of Stamos’ actions. It particularly lingers on the moments when Stamos adopts languid and seductive poses – his eyes on Crisp who casually savours Stamos’ naked form. The camera angle positions us looking from behind Stamos, and its hard not to see this as a film that sets up multiple-layers of gazing – the pleasure in watching Crisp’s pleasure in watching Stamos, who in turn take pleasure in being watched. There is an added layer added by the knowledge that Crisp himself earned his living for many years as a nude model for life-drawing (hence, The Naked Civil Servant) – now the subject rather than the object of the gaze.

This focus on Crisp’s gaze is foregrounded by the image on the second screen: a close-up of Crisp’s face, as he watches Stamos off screen. Without the sexual context of the subject of Crisp’s observation, the subtle shifts in Crisp’s eye-line and the sagging tones of his facial muscles humanise this ageing figure. The sexuality of the elderly is rarely a topic for conversation, but here it is clear to see the pleasure of this aspect of human nature is not limited to the lithe and toned. in both of Stamos’s frames there is the sense of a complicit circle of gazes, that rub sharply against the more removed gaze of Pacitti’s film. In downplaying Crisp’s iconic flamboyance, though, both films conjure a gently soulful, melancholic and elegiac sense of the ageing Crisp.

Where Pacitti and Stomos’s work deals with male relationships, Lauren Jane Williams’ Here is Not the Place for Nostalgia… is a phantasmagorical, sculptural landscape that almost literally turns the body inside out. Blending film, sculpture, body adornment, and performance, Williams crafts a world composed of three different-sized cubes: a television, a large aquarium and a performance space that resembles a shanty-town shack. These cubes are set into, for want of a better phrase, a hellish landscape of the fleshy fragments of particularly earthy dreams. A collision of human and animal flesh – breasts, feathers, penises, folds of skin – all meld with what appear to be other natural forms – trees, rocks, jewellery and bone.

On the TV, a short film of two naked performers in several rural settings plays out. They are connected at the chest by by a thin rope, sewn into the skin of their sternum. They move slowly, rising and falling, their umbilical connection tensing and releasing. In one frame they are surround by horses, who gently nuzzle them. In another, the two figures rise and fall within a stable.

On the right, the large glass aquarium paints a vision of fused human and animal parts. Real live crabs and clams are housed in a mini-tank inside the aquarium, bedecked with pearls. Atop this sits a mountain of ‘stuff’, organic and inorganic, topped by a cascade of jet-black feathers – damp and silky in the light. At points a human arm emerges – blood red finger nails echo the blades that cut into flesh on projections that back the central cube.

The centrally-placed shack contains two other naked female figures (not the ones in the video, and apparently there was a male body in the ‘shack’ on other occasions). One is stripped bare, and moves sinuously across the floor. With her mouth sewn up at one point, the second figure airbrushes her body with a fine mist of what looks like fake tan. This other figure, adorned in gaudy false eye-lashes, nails and wigs, shifts between posing for the audience, manipulating or administering to her partner, and reclining to insert metallic objects and jewels into her vagina and anus. These acts are carried out without fuss, but still retain a powerful theatricality. There is a deliberate invitation to the audience to approach the work and visually savour the texture of the bodies and the other materials. The measured manner of the performers heightens the feeling that Williams’s work sets out to render the body as fleshy matter. At times it is hauntingly beautiful, at others viscerally repellant – regardless of this, though, it is an uncompromising work that is always vigorously compelling.

Cassils: Inextinguishable Fire, Burn for Portrait 2015. Photo Heather Cassils with Robin Black

Just as physically courageous as Williams’s work was the closing performance of this year’s festival. In this, the artist Cassils presented a live version of Inextinguishable Fire for the first and last time. Titled after Harun Farocki’s 1969 film, in which Farocki addresses the way the audience might respond to images of napalm burns victims, Cassils work plays out in two parts. The first section saw Cassils perform a live act of self-immolation – a ‘fullburn’ stunt. Standing on the National Theatre’s Dorfmann stage, Cassils is systematically dressed in protective clothing and then set alight for a full 14 seconds.

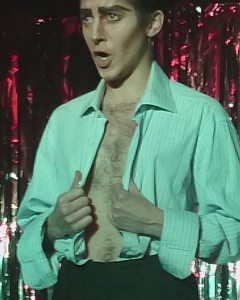

Three masked male figures carry out the dressing of the near-naked Cassils. The multiple layers of gel-covered, protective clothing forcing a shiver from Cassils’ naked skin. Like motor-racing pit-lane crew, they move with precision and alacrity – a kind of detached care for their subject. As the work begins, with Cassils standing naked except for a pair of briefs, it is hard to not to read the work in relation to Cassils trans identity. Such that, as Cassils endures the preparation, it feels as if it is an act of inuring the body against the forthcoming flames – a symbolic act of self-sacrifice that embodies the violence visited upon bodies that are ‘other’, whilst also acting as a bold statement of presence in front of the audience.

A short walk to an outside wall of the Royal Festival Hall, and the live event is followed by a 14-minute film. This film replays the 14-second burn, but in a slow-motion zoom-out from Cassils boiler suit-covered chest. As the camera gradually recedes from Cassils’ body, it creates a series of echoes: a masked villain in an action film; the Hollywood film The Hurt Locker; Joan of Arc at the stake; an immolated christ reaching out to his flock.

It recedes further. In the background a blood-red sky, marshmallow-clouds stained with reflected light of the flames: echoes of Platoon and Apocalypse Now spring to mind.

Still further, and the infrastructure of the film-making process becomes visible: the tracks for the camera dolly, fans blowing the flames away from Cassils’ face and then two masked figures emerging from the shadows. Their fire extinguishers drawn ready, for all intents and purposes this could be that action film – the bad guys running to gun down the hero. The CO2 gushes in strong, slow streams from the barrels of the extinguishers, washing Cassils in a white mist. It obscures this fallen figure, expunged from the landscape.

And then we are in reverse – the camera tracking back towards Cassils’ body, as Cassils slowly rises from the floor, Lazarus-like, to re-enact these previous poses. The camera tracks closer and closer, until the screen is just the white of the boiler suit again.

This shift between two states of obscuration echo Farocki’s observation that when we shut our eyes to pictures of napalm victims, ‘we close [our] eyes to the facts.’ Taken together, the live-action and the film serve as a meditation on the nature of violent images. They foreground the glamour of the image of destruction, the gloss of filmic images of war and terror, whilst at the same time revealing that these images aim to give us sensations, but not necessarily an emotional response.

As with Pacitti and Stamos’s and Lauren Jane Williams’s works Inextinguishable Fire opens a window onto heightened experiences and transformations – experiences that we can attempt to sense through their performances. These are communicated through our visceral response to the work – the way in which we take in, and respond to, the spirit of each of the works.

Interestingly, a further noticeable manifestation of the theme in some of the festival’s works is the way in which the artists set up a dialogue with times past: for Pacitti and Stamos it is the 1960s and 1990s, for Prior the 1970s, for Finley the 1980s and 90s, and for Robin Deacon the opening decades of the 21st century. In reaching back into these periods, each artist acts as a conductor (like a lightening rod) of the spirit of that time. By doing so, they allow us to understand the spirit of our own time, and the dialogues that need to be had.

Robin Deacon White Balance. Photo Chloe Pang

Featured image (top) is Lauren Jane Williams’ Here is Not the Place for Nostalgia… Photo by Manuel Vason / DARC for SPILL

SPILL Festival of Performance ran 28 October to 8 November 2015. Karen Finley’s Ribbon Gate installation continues at the Barbican until December 2015. See www.spillfestival.com for full details of all works, and also for SPILL TV, writings, and other documentation.