Thomas Wilson reflects on three very different contemporary circus-theatre shows seen at the London International Mime Festival 2018

London International Mime Festival enters its 41st year, and as usual proves to be the single best place to get a glimpse of the diversity of visual and physical performance currently around. This year is no different, from the surreal beauty of Brussels-based Peeping Tom’s physical/dance theatre, to the physical comedy of New Zealanders Trygve Wakenshaw and Barnie Duncan, and the gentle humanity of British mask company Vamos.

It is also a place that you can catch some of the most interesting contemporary circus performers from around the world, including Finland’s Kalle Nio, whose show Lähtö opened the Festival; French artists Laurent Cabrol and Elsa de Witte with their intimate circus-puppetry piece, Bêtes de Foire – Petit théâtre de gestes; and perennial favourites, Compagnie Mpta, who this year presented Santa Madera, a two-man Cyr wheel show created by Argentinian Juan Ignacio Tula and Swiss-Costa Rican Stefan Kinsman under the guidance of French circus maestro and renowned acrobat, Mathurin Bolze.

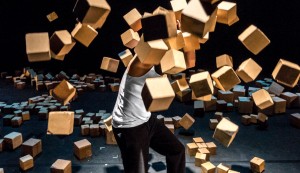

The Festival also welcomed not one but two Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2017 Total Theatre Award winners. Gandini Juggling’s Sigma, which explores the creative interface between juggling, geometry and classical Indian dance, won an Award for Physical and Visual Performance. The Total Theatre and Jacksons Lane Award for Circus went to Fauna, which is presented, unsurprisingly, in association with Jacksons Lane. Fauna are a young company of five, they are all graduates of Sweden’s circus school powerhouse DOCH, and their eponymous show (a blend of trapeze, hand-balancing, tumbling, and stacking) hums with a youthful energy. Constructed from their enquiry into the relationship between circus bodies, animals and sound, Fauna manages to be playfully innocent whilst weaving darker moments throughout the hour-long show.

Fauna. Photo Kate Pardey

The inquisitive nature of the work results in Fauna finding some genuinely interesting interpretations and alterations of existing circus tricks and tropes, and helps it sustain the pace of the work as a whole. It is most compelling when the body is made strange – not through acrobatic tricks but rather through simple flexions, rotations, and (insect-like) articulations of the joints that disrupt the recognisable form of the body. This motif runs throughout the work, and alongside simple (and sometimes a little too simplistic) clown play, embellishes the quintet of characters who traverse the bare stage.

In this there are some genuinely striking moments, particularly when the physical articulations are accentuated with different rhythms. For example, as Enni-Maria Lymi hangs from the swinging trapeze she rotates and flexes the elbow and shoulder joints, as if testing the limits of her limbs like a hatching mantis. In doing so, the trapeze is forgotten and instead her body takes on a strange and alien form. This is circus where physical discoveries set up a productive tension with the trick or known form of the body.

This is not to say that Fauna don’t offer spectacular tricks, because they do. It’s just that at times these tricks feel like they are a youthful exuberance rather than fully sitting in the world they have established. A male duet midway through the performance, although dynamic and punchily delivered, is rather cold, lacking the clarity of purpose and nuance of characterisation as the previous scenes, and so it feels out of place. It’s thrillingly athletic, though, and more of a question of framing than quality of the material.

In their defence, it’s important to note the way that Fauna sustains tricks beyond the point where a more ‘trick-orientated’ circus show might stop: instead exploring the possibilities that occur when a trick is sustained. This is intriguingly the case in Daniel Cave-Walker’s head balance, which once established (and when the audience goes to applaud) carries on. Cave-Walker remains in this position and then slowly begins an insect-like articulation of the leg joints, elongating the head-balance until it ceases to become an astonishing trick and instead transforms into something more compelling – a strange inverted creature whose leg-antennae attempt to sense the air.

It is the female performers in this work who stand out in terms of character: Rhiannon Cave-Walker has an easy knowing charm, persuading her partner to (literally) play with her in a game of falling and catching whilst avoiding an overly laboured quality. There is a mature air to her work, and one that doesn’t need to work the audience too hard.

Enni-Maria Lymi works at the other end of the spectrum, the innocent trying to make sense of her world, with a direct and explicit audience relationship. Her charming attempt to understand the trapeze is a highlight of the show, particularly in the way she builds the tempo and dramaturgy of the vignette. Her characterisation risks becoming a little too broad and simplistic later on but doesn’t quite tip over into that territory.

Geordie Little’s music composition and soundscape – an intriguing mix of acoustic flamenco guitar with sampled and looped sounds and beats – is the driving force of the work. In fact (given the bare stage) it is another character, that also contextualises the action in an unobtrusive but efficient manner. There are moments where the relationship is explicitly stated, the sound cutting out and the performers pausing deliberately awaiting the resumption of the sound is one such moment.

In essence, Fauna works because it embraces the fact that the human body is a meaning-making tool, even if working with formal tricks and abstraction. Although not fully polished, and with some simplistic elements it is nonetheless a great debut work.

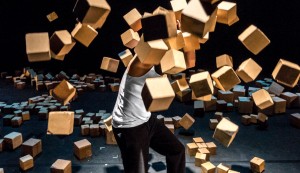

Nacho Flore: Tesseract. Photo Erik Damiano

Former Moscow State circus artist, Nacho Flores’ Tesseract is also a piece that sets out to make a bold statement, though this time it is for Flores’ inventive and novel choice of balancing apparatus. Although trained as a high-wire specialist, Flores’ chosen apparatus is a host of wooden cubes, of myriad sizes, stacked into neat towering columns across the stage. With these Flores presents a series of ostensively unconnected scenes.

Tesseract opens with Flores’ stood atop one column, a metre from the ground, and holding a pint of water. This column is only one in a snaking line of many others, wending its way across and down stage until it meets a small chair balanced precariously on four taller columns. Then comes a table, also balanced on four taller columns; and finally a plant perched precariously atop a final, thicker, and even taller column. What follows is a simple-looking, but increasingly tense, journey along the top of these columns towards the table. There are collapsing columns, spilt water, and heart-stopping moments. Flores has an easy charm, and his amplified vocal hums, oohs, and errs ensure that the dramatic tension of this journey is sustained – until in one final crash columns and all collapse.

The following scenes repeat this same pattern (after all what goes up must come down), but Flores finds a variety of ways of stacking and deploying the cubes. There are, for instance, some touching ‘cubist’ human figures and a charming block-puppet. Most impressive though is Flores’ ability to flip, rotate, spin and balance one cube on another, all whilst standing on it. This is pure, gob-stopping classic circus and as such a real crowd-pleaser and the highlight of the show.

For his finale, Flores integrates his balancing with cutting-edge 3D video mapping. It’s an interesting development, but one that appears to reduce his opportunity to explore his core skill of balancing. Instead, there is a trade-off that lets the projection produce the tension and instead (at times) Flores’ seems to become a facilitator for the animated images.

However, despite these rough edges, it’s enjoyable to see a show that originates in a genuinely inventive approach to apparatus and a search for new skills, declaring this openly and without the window-dressing of a wider theme. And, whilst the dramaturgy of the show is a little clunky (endings are a little anti-climactic, some moments a little too long, and the jumps from scene to scene need something to bridge them), the technical artistry is thoroughly enjoyable.

Sacekripa: Vu. Photo Alexis-Dorc

Sacekripa’s Vu is a very different beast. A solo from a collective of experienced circus artists that has grown out of the famous Lido circus school in Toulouse, back for their second Mime Festival appearance following the success of two-man show Maree Basse. Vu is one of those shows you wished you had made yourself: simple in conception, nuanced in execution, and utterly beguiling. The premise is simple: a single performer makes a cup of tea. So simple in fact that it could almost be (actually it is) an actor’s training exercise. But when your actor is a circus performer of this calibre, strange and compelling things become possible, and making a cup of tea becomes a microcosm of the world.

As with Brook’s maxim, Vu begins with a single performer entering the space. In the space a slightly raised wooden platform, a low table, a tiny chair, and a slowly revealed host of props. What results from this simple situation is a gradually increasing level of fastidious complexity in the ways that simple tasks, such as putting a tea bag in a mug or lighting a candle, can be achieved in the most complex manner (in this world, both examples require the use of a blowpipe). What results is a kind of delightful, perverse efficiency, so much so that it would be criminal to reveal more for fear of ruining the surprise.

Think then instead of a solitary Gallic version of Morecambe and Wise’s legendary breakfast routine, played at Harold Pinter-speed, but with melancholy and resignation as the principal tones, and only a cup of tea for salvation. The timing of surprises is impeccable, and the repetitive inclusion of an audience member masterfully handled. This latter element ensures the technical mastery and inventiveness doesn’t become alienating: the whole relationship with the audience is handled with such a casual disdain (tempered with occasional praise) that you’d think performer Etienne Manceau was a particularly grumpy school teacher.

By the end, Vu is an articulation of the idiosyncrasies of an individual’s daily life (tea before milk, dunk don’t stir the tea bag, two lumps or three) taken to their absurd conclusion. This means we are treated to acrobatic sugar cubes, meticulously measured milk, and the most complex way of striking a match you’re likely to see.

What makes Sacekripa’s work stand out is the genuine innovation of their tricks, and the way Vu hovers between a classic vaudevillian approach to the sketch (especially in the meticulously inventive detail) and the quiet frustrations of absurdist drama. It is no surprise that the company are mostly jugglers – for who knows failure, objects and precision like the juggler, and who shoulders that with quiet and firm resignation to keep on going? That might well be the message of Vu, but you’ll be too entranced to really bother considering such things.

Fauna: Fauna was presented at Jacksons Lane, 11–14 January 2018; Sacekripa: Vu at Shoreditch Town Hall, 25–27 January 2018; Nacho Flores: Tesseract at Jacksons Lane, 26–28 January 2018.

For full details of all shows and events in the London International Mime Festival 2018, see www.mimelondon.com