Well, that wasn’t what I was expecting! Dickie Beau has a formidable reputation as a cabaret and nouvelle drag artiste, but in recent years has also created full-length theatre works. Blackouts: Twilight of the Idols ‘conjures the spirits of celebrated Hollywood icons’ and ‘channels the ghosts of his childhood idols’ – but that’s not the unexpected element. It’s the form that surprised me.

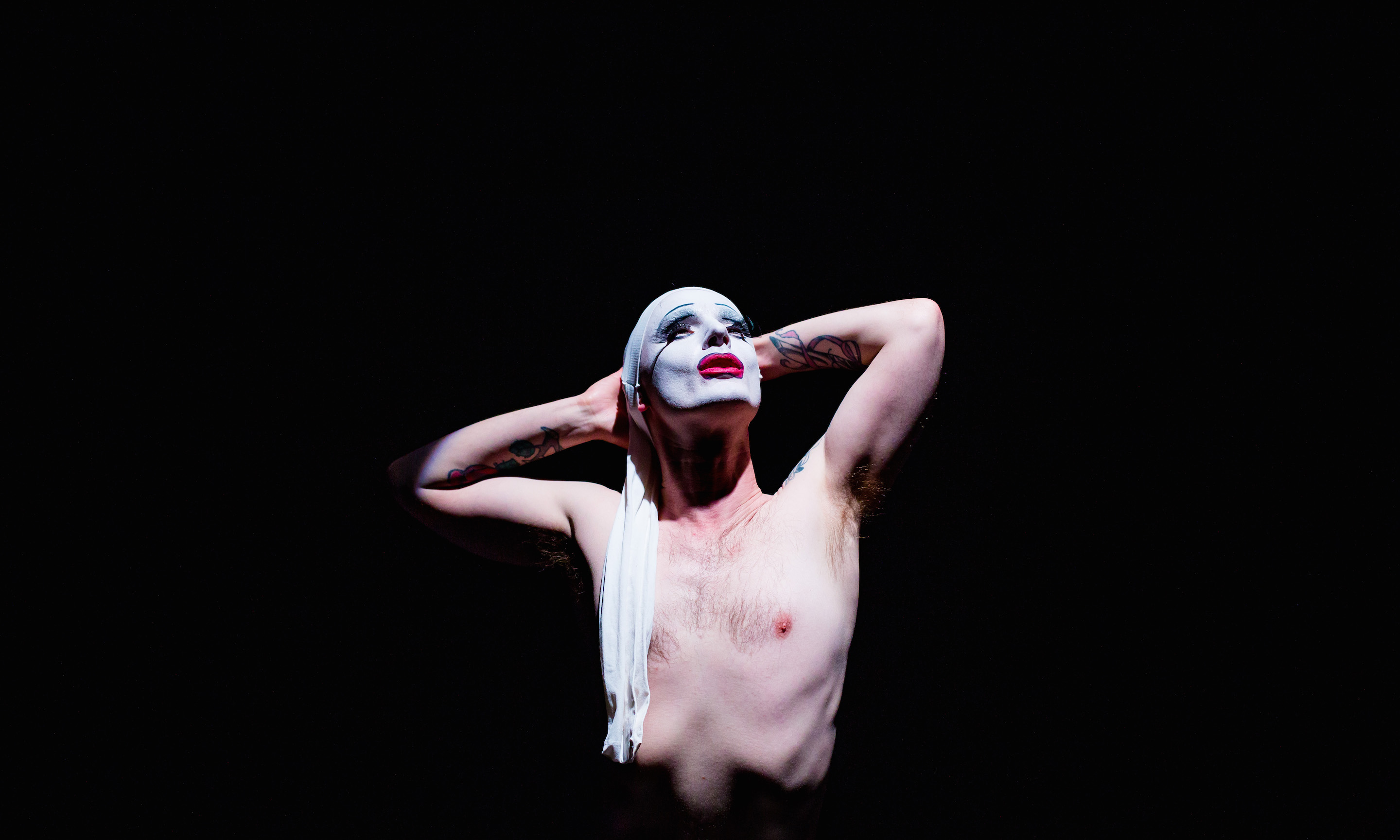

For the show – or the first half of it, at any rate – is a classic piece of physical/visual/total theatre. Precise physical performance that references traditional mime, evoking the early white-face work of Lindsay Kemp; an interesting casting of objects with dramaturgical significance (an ancient reel-to-reel tape machine; a black shiny rotary-dial telephone) allowed to sit, lit beautifully, on stage for us to relate to as characters in the story; the performance space veiled by a thin gauze on which words and images are projected, creating a multi-layered onstage world.

This first half mostly concerns itself with Marilyn Monroe, and a recording of her last ever interview in spring 1962 – just days before she died – with Richard Meryman for LIFE magazine. But here’s the really exciting twist – included in the show is not only the verbatim recordings of Marilyn’s voice, but also an interview with the interviewer, Meryman, reflecting on the process, on the content of the interview, on the writing and editing decisions (the piece was published as a first-person monologue), and on the star’s death.

We are thus presented with an intricate theatrical web that invites all sorts of reflections on the nature of truth, artifice, disclosure, and exposure. Whose story is this? Is it Marilyn’s, is it Meryman’s, is it the media’s, is it Dickie Beau’s? It’s all of the above. Beau’s relationship to it all is complex and multi-layered, readily mixing fantasy and reality (whatever that might be), deliberately playing on notions of mediation and interpretation. He lip-synchs both Marilyn and Meryman’s words as we stare at the cumbersome tape machine. With Beau as the medium, she tells us she wants to study and be taken seriously; he tells us that he turned up at her Hollywood home without even knowing how to work the machine, and that she was tired and listless and trying to wriggle out of the interview, until a trip to the bathroom for a ‘liver shot’ that revived her miraculously. Mostly, Dickie Beau is in his neutral ‘mime’ outfit, but in one short and beautifully enacted scene, he dons a blonde wig and a white satin dress and stands before us, recreating the iconic Marilyn skirt-blowing moment that we all know and love.

The second half of the show similarly works with the recorded voice of an idol. In this case, it is Judy Garland’s dictaphone notes for a memoir that was never written. This section of the show in fact came first, having evolved from a 10-minute cabaret/short theatre piece that Dickie Beau has performed for a number of years. It’s clever, and ultra camp. ‘Judy’ is dressed head-to-toe in blood red – plaits, a flouncy skirt, striped socks, and ruby red shoes that sparkle and glitter under the lights. Wielding a knife, she’s a kind of hybrid horror-film mix of Dorothy and a reversed-out (red rather than green) Wicked Witch – sitting, standing, tottering on those red shoes as she mutters about looking out for her little girl Liza, and how she hates always playing ‘herself’ – she badly needs time off from being Judy Garland. Lacking the multiplicity of layers of the first half of the show, being a far more direct portrayal of a drag character, this section is entertaining but nothing like as exciting or thought-provoking as the earlier part.

But skill wins out. Despite not being quite as enchanted by the latter part of the show, I’m bowled over by Beau’s skill – his ‘Judy’ is undoubtably a brilliant characterisation. But for me the heart of the work is the Meryman interview, and the way that this is so cleverly unpicked and moulded into Beau’s reflection on his relationship to the Monroe myth. It is interesting to see that Dickie Beau, in his programme notes, dedicates the show to Richard Meryman, who died in February 2015.

Blackouts is not quite the perfect piece of theatre it could have been, but it is a highly commendable show, expertly performed, and a delight to witness.