Where does agency end and voyeurism begin? Performance artist Eloina Haines explores censorship, ownership, and what happens when the physical performer is absent and only the online image remains.

Valentine’s Day 2020. I am towering over a sweaty audience in the equally sweaty Vaults tunnels in London. Two male performers, attached to my wrists by leashes, are waxing my legs. A bouquet of roses is flowering from the opening of my cunt. I am utterly naked.

The music swells and the lights come up. I see a flash from the audience which is not a strobe light.

‘STOP THE FUCKING MUSIC,’ I say.

The audience falls silent and my naked body feels extremely exposed.

“THIS. – referring to my body – IS. MINE. NOT. YOURS.

I am choosing to share it with you. That does not mean that you get to share it elsewhere.

So read the fucking signs and put the fucking cameras away. Just like yours is yours, this, is mine.

Does that make sense?’

Moving the corners of my mouth to smile at them, I coax, ‘CAN I GET A HELL FUCKING YES!?’

The crowd erupts: ‘HELL FUCKING! YES!’

‘Good,’ I say, ‘LET’S PLAY THE FUCKING MUSIC THEN!’

As a performance artist creating work that de-censors the female body and dismantles its taboos, I usually perform nude. Because of this, I dreaded putting my performance art online during the first UK lockdown in 2020. I feared it being censored and the lack of agency I could maintain over it: I could no longer have venue staff policing no-photography whilst I pulled a PLAYMOBIL man from my vagina; no longer position myself at a height over the audience to watch out for cameras; no longer call someone out for recording me and turn the audience against them if they refused to delete it. Online, I have no control.

Usually, I sign a silent contract with the audience, formed of knowing looks and rules. This is an understanding that I am letting them into parts of my body and life that are generally kept private, yet that whilst on stage, I am in control of how that happens. Online, however, I cannot have this presence. Viewers are not experiencing these moments with me. Instead, they are voyeuristically able to curate the experience themselves. They may play, pause, rewind at any time they like. They may zoom in, screenshot, and send on. The moment that the work is put online, the live presence of the nude performer is taken away. Consequently, their agency ends and voyeurism begins.

I still yearned to make bold work during lockdown. Live performances in theatres and galleries were banned, but my creativity had not stopped. So I channelled it into visual art. I began to paint portraits using a paint brush inserted into my vagina. I did precisely-placed push-ups onto the page so my inky bush could form the hair of my subjects. The results were impressive, if my cunt does say so herself. It was empowering; I was once again taking control over my body to create art.

I shared a picture of the finished product on Instagram, along with a sped-up video capturing the process of my squat-painting. The empowered and excited feedback was equalled by that of disgust and disapproval. In underground cabaret venues in London, most people would have seen a performer pulling something out of their vagina to make a political statement, at least once. However, when you take that out of context and place it online to be shared between thousands of networks of people, you reach those who you are really trying to fight against. Though this far-spread audience are the people I want to get my message of agency and de-censorship across to, it was their messages being hurled at me; I was voiceless with no presence or space to have these wider conversations.

Soon, the vagina painting and its process video were taken down from Instagram without my consent or knowledge. Consequential conversations revealed that the same was happening to many of my performance art peers: Instagram algorithms were banning posts for ‘nudity’ or ‘pornography’ without assessing them properly, threatening to delete artist accounts, and only reinstating those with large followings.

When it comes to the nude female body and contemporary social media, there is a thin line between what is publicly considered ‘art’, and what is considered sexual and obscene. This is no surprise considering the guidelines set on artistic depictions of the nude female body throughout history. Before the 5th century BC, for example, female body parts were only shown in art when the woman was a prostitute or a victim of violence. This set a solid foundation for women to be viewed as broken, sexual, and surrounded by negative connotations in art and life.

In the mid-4th century BC, an image of the Goddess Aphrodite was sculpted nude. Though extremely controversial, as Aphrodite was neither a victim nor prostitute, the nude artwork was deemed acceptable because the Goddess was a highly-respected figure and of course, the genitals were completely removed. Yes, this was the first Barbie doll.

The same bullshit limitations continued into the 19th century. When it came to neo-classical depictions of a woman’s body, the Royal Academies deemed what was acceptable and successful. Nude female figures were required to be in ‘sensible’ and non-voyeuristic positions – predominantly reclining or relaxed, not bending down or squatting. In other words, the woman’s position had to be passive, not active. Within these standards, female bodies became ‘other’, distant and representative of a narrow and mundane existence.

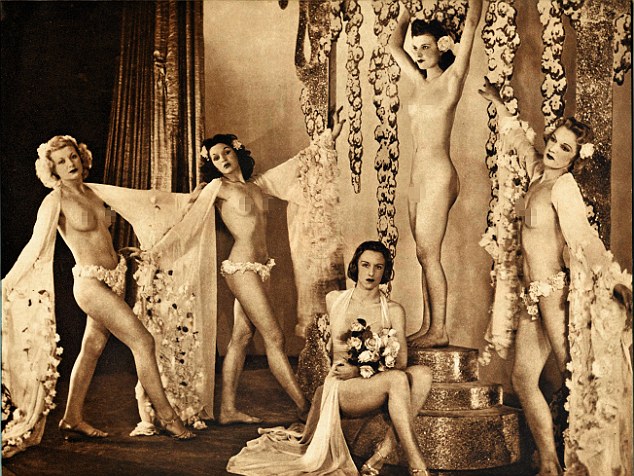

Similar standards were set for performance in early 20th century London. The censor had ruled that nudity in theatres was obscene, yet could not say the same for nude female statues around the city. The Windmill Theatre used this as a loophole: they argued that if the naked female performers were motionless, then they were no less morally objectionable than statues. To keep within the laws, the women were revealed on stage, holding stationary nude poses. Only the props around them – fans, veils – would be moved by other, clothed, women. It seems that historically, the female body being nude is not the problem: it is when the woman is seen to be in control of it that it is deemed unacceptable.

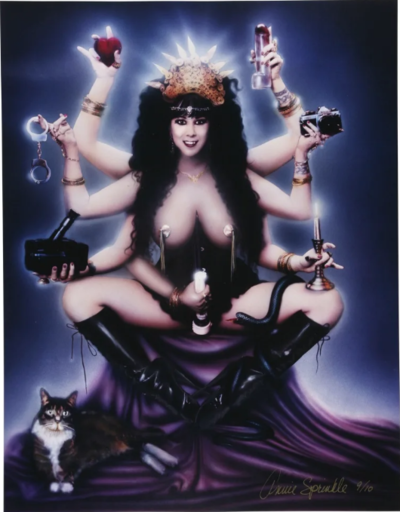

Eventually, the Theatres Act 1968 abolished censorship on UK stages. Explicit shows were no longer reserved for underground members’ clubs, and shows like Oh! Calcutta! came to the West End, containing sexual discussions and fully-nude casts. In the following years came a monumental rise of ground-breaking female performance artists. Cosey Fanni Tutti and Annie Sprinkle were infiltrating the porn industries and changing them from the inside out. Carolee Schneemann was using nudity in performance to break taboos in gallery spaces, detach sex-negative views imposed on women, and ‘(give) our bodies back to ourselves’. At the same time, Marina Abramović began staging her first solo performances, iconically testing the power she had over her body’s limits, before later choosing to give some of that agency to her audiences.

These artists, to name but a few, and their agency-filled work paved the way for contemporary performers such as Ursula Martinez.

Martinez’ show Hanky Panky redefines the customary striptease and reimagines a classic magic trick. Throughout the act, she makes a hanky disappear, revealing it from a different item of clothing each time, which she then removes. The last time the hanky disappears into her hand, she is already entirely naked. Then, with a knowing wink and look, she pulls the hanky out from her vagina.

Martinez moves through the cabaret spaces she performs this act in with authority, thrusting in audience member’s faces to the music, making them blush, constantly retaining control of the situation. She completes all the disappearing acts and removes her clothes herself, unprompted by anyone else, whilst holding intensely engaging and self-aware eye contact with her subjects.

In 2006, Martinez’ subversively erotic act, which steams with powerful self-possession, was unfortunately filmed and uploaded to YouTube and porn sites without her consent. Consequently, her inbox was flooded with messages from men looking for a bit more from her, sending her unwarranted photos of their genitalia, and even asking her to marry them. The agency she held over her body had switched to the voyeurs; they felt the power to take her body into their own, virtual hands. When the show transformed from live to recorded, Martinez’ relationship with the audience disappeared. This loss of her presence forms a space where the fantasies of the voyeur can play out. As they have the power to press play, pause and rewind, they own the agency over the experience and how much space they take up within it. In live performance, the performer’s presence is overriding. However in online performance, the viewer’s eye becomes dominant.

In a mighty feat of reclamation of her work and body, Martinez wrote a show called My Stories, Your Emails. This consisted of personal, family anecdotes and a slideshow containing the most crude, intrusive emails she received after Hanky Panky went online. She played these men at their own game; just as they had taken power over her images, they had given her the power over theirs. She holds the agency over their dick pics and even gives some of that power to her audience, who laugh along at the slimy messages and photos. Although the audience is aware of how much Martinez’ loss of agency and therefore, identity, pained her, they are happy to watch as she does the same to these men. Regardless of moral integrity, the message Martinez delivers is clear: once an image is online, it is no longer yours.

In this current online era of 2020, I wonder if it is really possible for agency to be maintained, and censorship to be defied for nude performance art. Fortunately, unlike Instagram, platforms such as Vimeo and Patreon acknowledge and allow creative nudity within their guidelines, as long as it is marked as ‘mature content’. This means that artistic nude material is not taken down from their sites and it is assessed accordingly, without being deleted as soon as their robots identify flesh. They also allow you to restrict access to your work with password protection and paywalls. Despite their acceptance of artistic nudity feeling like an open door for online performance art, there is still the issue of the viewer’s ability to easily screen-record or screen-shot your work to keep for personal use or send on further.

The nature of online performance is naturally voyeuristic. The viewers behind their screens, and the platforms that host it, hold the agency. They have the power to take your work out of context, out of your hands, and into somewhere where you have no control. This is terrifying when the work being made requires such present connection, trust and vulnerability.

I have not yet been able to release work online since Instagram censored my vagina painting, and I do not know if I ever will. Perhaps it will mean reshaping my practice entirely and eliminating nudity, which defeats my aim to de-censor the female body. Perhaps I should just try to trust my viewers, as Martinez did? Perhaps I should simply reconstruct my genitals to look like Barbie’s so I can get away with it?

But alas, I am no sculptor.

Back to Valentine’s Day 2020. The audience whistle and wince as, one by one, I slowly pull the bouquet of red roses from my cunt. I tease giving it to an audience member, think better of it and give it to myself instead, cheekily reinstating ‘they’re mine, they’re for me’. I decide to prompt the audience to throw the 100 red roses I had left for them on their tables at me – reminding them that this body is mine, and that I choose to share it with them in order to respect, celebrate and empower it, along with their own. The collective appreciation of this moment is beautiful.

That space of mutual honour is sacred. And I hope it can exist online soon, too.

On. Our. Terms.

Featured image (top): Eloina Haines: Fish Don’t Bleed

Eloina Haines is a London-based performance artist and comedy clown. She took part in the Total Theatre Artists as Writers programme 2020. @eloinaaart

https://www.instagram.com/eloinaaart/

References:

Ursula Martinez: Hanky Panky and My Stories, Your Emails:

www.ursulamartinez.com

Carolee Schneemann, Cezanne, She was a Great Painter (New York: Trespass Press, 1975), p.24.

Classical and Neo-classical depictions of the female nude:

https://medium.com/@richardkyu/tracking-the-historical-representation-of-the-female-nude-2d1d7fe1d1d

Theatres Act 1968

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1968/54/pdfs/ukpga_19680054_en.pdf

Vimeo Guidelines:

https://vimeo.com/help/guidelines

Patreon Guidelines: