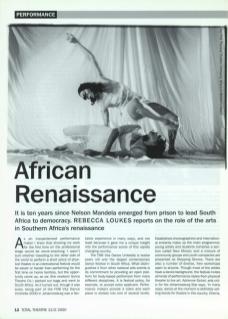

As an inexperienced performance maker I knew that showing my work for the first time on the professional stage would be nerve-wracking, I wasn't sure whether travelling to the other side of the world to perform a short piece of physical theatre in an international festival would be easier or harder than performing for the first time on home territory, but the opportunity came up, so we (the newborn Soma Theatre Co.) packed our bags and went to South Africa. As it turned out, though it was scary, being part of the FNB Vita Dance Umbrella 2000 in Johannesburg was a fantastic experience in many ways, and not least because it gave me a unique insight into the performance scene of this rapidly changing country.

The FNB Vita Dance Umbrella is twelve years old and the largest contemporary dance festival in South Africa. What distinguishes it from other national arts events is its commitment to providing an open platform for body-based performers from many different disciplines. It is festival policy, for example, to accept every applicant. Performance makers provide a video and each piece is slotted into one of several levels.

Established choreographers and international entrants make up the main programme; young artists and students comprise a section called New Moves; and a mixture of community groups and youth companies are presented as Stepping Stones. There are also a number of diverse, free workshops open to anyone. Though most of the artists have a dance background, the festival invites all kinds of performance styles from physical theatre to live art. Adrienne Sichel, arts critic for the Johannesburg Star says, 'In many ways, dance at the moment is definitely setting trends for theatre in this country. Drama, as we've known it, has died. It's a whole new era.’

It's a whole new era for South Africa too: ten years since Nelson Mandela was released from Robben Island, signalling the end of apartheid, and almost a year since Thabo Mbeki became president. Both before and after his inauguration, Mbeki has widely promoted the notion of an African Renaissance – a rebirth for the country with a host of new social and economic possibilities. Speaking at a national conference on the subject he has said: 'We must recall everything that is good and inspiring in our past. Our arts should celebrate both our humanity and our capabilities to free ourselves from backwardness and subservience.'

In this relatively new period of racial equality, it is not possible to look at the future of the arts in South Africa without recognising the effects of the past. Georgina Thomson, artistic director of the festival, claims that because the FNB Vita Dance Umbrella has always been a completely democratic platform there are not the same post-apartheid tensions that exist in the South African theatre world. Theatre, she says, operated on a whites-only basis as late as 1988. This meant that Theatre Management (the then National Arts Council) funded only white companies and productions. Development and training was focused on the white population until the late 1980s, with most other groups being given minimal opportunities. International sanctions also meant that few theatre or dance companies visited South Africa, and performers were forced to leave the country to further their training. Thomson says, 'For some time the then Arts Council, who received all government funding, thought we could cope without the rest of the planet. This, of course, left repercussions which are still felt today.'

In many ways, dance at the moment is definitely setting trends for theatre in this country. Drama, as we've known it, has died. It's a whole new era.

New Moves, the section in the festival for young, up-and-coming choreographers, perhaps illustrates these effects. Thomson acknowledges that the pieces this year were disappointing. Sichel was more direct with her criticism in the Star, stating that the works mostly 'exhibited a shocking regression or stagnation in choreographic and performance levels'. She claims that it demonstrates a need for a re-evaluation of the training of performance makers, acknowledged as an old South African problem, and now 'a life threatening fault line'.

Importantly, the companies that fought the old system were primarily employing their skills to bring about social and political change. Many performers engaged with immediate issues of apartheid in highly imaginative and collaborative ways. Handspring Puppet Company, for example, drew on puppetry, film and live performance and received worldwide acclaim for its productions of Woyzeck on the Highveld and Faustus in Africa.

Without this immediate agenda of protest, however, it has been suggested that there is currently a search for a kind of national identity within post-apartheid South African performance. Indeed, Thomson notes that in this year's festival companies were less focused on a message within their work and more concerned with experimenting with new performance aesthetics. Gary Gordon's Durban-based First Physical Theatre Company was commissioned to create Who's in Bessie's Head?, a seventy-minute work that looks at the life of a female South African writer, born in a mental institution. The company is widely seen as one of the templates for physical theatre in the country, and their style draws heavily on dance, but also employs voice and sound. Gordon thinks that collaboration and experimentation are the way forward, and that physical theatre challenges people's perceptions of the way work is made. This does not, however, mean avoiding the political. Though the apartheid days are over there is still plenty to question. South Africa has one of the highest rates of violent crime in the world, which reveals an underlying crisis in employment and housing. So where does this leave the arts? Thomson is sure, at present, that Mbeki does not include dance and theatre in his vision of an African Renaissance, as funding for the arts is dwindling, and there seems to be no focus on developing it at any level.

But is the festival reflecting what is happening in the arts in the rest of the country? By offering itself as a free platform for all kinds of performers, the FNB Vita Dance Umbrella celebrates diversity rather than attempting to address any question of a South African identity. And this surely should be the way forward. In a country with eleven official languages and a history of complex body-based theatre and dance practices, as well as international influences to draw on, the search for any one identity seems pointless. Staging contrasting and contradictory works side by side says as much about a new era of performance as the content of the work itself. And audiences at this year's festival were treated to some question-raising pieces. There was Steven Cohen's Limping into the African Renaissance, which examines his South African, gay, Jewish identity, and also The Performing Rites' controversial Amadlozi, Amandiki, Amandawe, Izizwe Nguni Spirit Possession presenting a group of sangomas (shamans) going into full trance on stage. There were top South African dancers and choreographers Vincent Mantsoe and Robyn Orlin, and several pieces by the twenty year-old Moving Into Dance Company, which, from its inception, has focused on the training of black performers.

Perhaps these programme notes from a devised work by three choreographers say what is needed on the subject of identity: 'Our bodies are different, as are our languages, images and dreams. It would be tempting to merely juxtapose our different skin colours, but this is clearly not enough. There is no use looking for difference either – the difference is not a source in itself. The only one, the real one, is that we dance, and that we wish to dance together.'

As for the future of physical theatre, as Thomson points out, the term is currently mostly associated with white companies who have dance training and an eye on the work of Lloyd Newson's DV8. However, if festivals like FNB Vita Dance Umbrella continue to embrace and nurture cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary performance (and training) at every level, all manner of exciting and diverse collaborations are possible. It's definitely an exciting time to be watching South African performance.