Where did it all begin?

I started out as an actor. Then I wrote some plays for television and the stage in the 60s. I directed the shallow-end of a water show, then I founded my own comedy company. Bob Hoskins was one of the lead comics, and Sylvester McCoy. It was called Ken Campbell's Roadshow. Then I got involved with science fiction and I founded the Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool, where we did only science fiction plays, of which The Warp was one. It's not really science fiction, but it's kind of on the same shelf – it's wacky first-hand experiences, so it's on the UFO / strange experiences shelf.

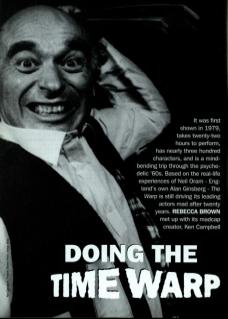

What inspired The Warp?

The Warp isn't really mine. I just listened to – and wrote down – the real-life experiences of one man, Neil Oram. I was a kind of amanuensis and at some stages something of an editor. Some of Neil's story bored me. I thought some of it might bore others. So The Warp by no means presents his entire life story. There aren't any other British plays that cover the 60s in this way. The Warp presents the memories of real people. There's no other record of any of the people it brings to the fore; whereas the equivalent people in America are really quite well known, due to the writings of Kerouac, Ginsberg, Thomas Wolfe and those sorts of people. No one from our 'alternative communities' was ever much of a literary chap, except perhaps Heathcote Williams, who is a brilliant writer, but didn't actually record what was going on in the 60s. He wrote brilliant things beside it – to do with it – and plugged into it; whereas The Warp is Neil's actual account of events.

Why does The Warp take as long as twenty-two hours to perform?

The Warp might as well take this long, because the material it covers doesn't exist in alternative forms and the actors enjoy performing it at this length. The Warp exists in whatever form the actors want to gather together and do it. I think the big adventure of doing the show is its length. I don't think there would be a great attraction in just doing one of the plays it comprises, or doing a two-hour version, because that wouldn't be it.

When was The Warp first performed and how has it developed over the years?

The Warp was first performed in 1979. It opened as a serial at the ICA. We did five plays one week and five plays the next week. Quite large sections were performed during the days and evenings, on a daily basis, then the whole thing was done in one wallop. And once it had been done that way, this was how the company wanted to do it, because they loved it. They then went on to do five full shows at the Edinburgh Festival, then they did it for the hippies of Hebdon Bridge. There were also five performances at The Roundhouse and later on it had a very successful run, as a serial, at The Everyman Theatre in Liverpool.

How many actors have played the lead?

The early performances were all done with the same leading man, Russell Denton. But it's a thrash on the brain and he wound up knowing more about the author than he knew about himself, so he retired. The lead was then taken over by an actor called Alan Cox, who did a fantastic performance at Three Mills Island. But he had to be wrapped up, massaged and talked to lovingly, because he forgot who he was – he had a psychotic episode. I instructed this Vietnamese violinist who was there to 'accompany the chaos', so she played, while he recovered and eventually he felt he had to see it through to the end. It took twenty-nine hours. Then at one point my daughter Daisy learnt the part as a kind of personal challenge, and there was a private go through for her, but she didn't do it again. More recently the part has been played by a young actor called Oliver Senton, who did a run at The Albany in Deptford last year directed by my daughter, and then at The Spitz in Spitalfields Market, and this year at Hoxton Hall.

So can only certain kinds of actors perform in The Warp?

There are some actors who don't really like acting, they are merely quite good at it. There is a kind of professional actor who is like that. They go in, they get themselves together and they're rather good, but then they go home, or off to the pub, and do their own thing. Then there are other actors who are a bit like jazz musicians, who like to go on jazzing after a gig. You'll find that some actors go acting and performing in bars through the night, and for that sort, The Warp's ideal because it's like never-ending acting. Performing in the show does strange things to you. It enters your dreamtime and, because you're acting through your own dreamtime, it actually enters that part of the brain and becomes very regular. All the people get bonded together in The Warp, because you have to look after each other much more than in an ordinary show. You have to be aware of scenes that you're not in and know what follows your scene and check that the person's awake! I like it when they do the whole thing in one go and half the audience have fallen asleep. Sometimes I make hot soup and bring it round. It's like the Blitz, or something. It's over much quicker then.

Are you an actor as well as a director?

I stopped acting. I got taken off the list. Acting is a calling, you get called to act, and you can get called in and removed from the list. It happened to me more than twenty years ago now, when I was at the Nottingham Playhouse in Richard Eyre's production of The Alchemist. I was playing the Alchemist and it was the last night. I'd done the matinee and I delivered a speech and an angel appeared and said, 'We're taking you off the list.' So I said, 'Well, this is a damn silly time to choose because I've only got one more show to do.' So, I got to the end of it and I just didn't act anymore. The angel came back though, and said small parts in TV and film would be alright.

Why did you stop acting?

It was only really ‘play-phobia', it wasn't audience-phobia. I like audiences, so this kind of led me into doing my own shows, where I just sort of talk to an audience. The angel doesn't seem to mind that, because I'm a performer rather than an actor. I call an 'actor’ someone who's in plays, pretending to be someone else. I am a director, but I have never put myself forward to join the who can direct The Cherry Orchard the best competition. I think I'd be a bit depressed if I won it. It's not my area, so I really only direct things that wouldn't go on if I didn't do them. I'm more into starting up new things.

What inspires your one-man shows?

I like having an audience and working the audience. I like making them laugh, and occasionally I like making them cry. I'm not a stand up comedian. I'm probably a sit-down tragedian and a humorist. As subject matter goes, I'm really only interested in the remote, the remarkable, the weird, the odd and out-of-the-normal run of things. So my shows are just basically about things that rivet me. I've done many of these. They normally have formal titles: The Recollections of a Furtive Nudist, Six Pigs from Happiness, Jamais Vous, Mystery Bruises, Knocked Sideways, Violin Time and Theatre Stories. These are all two hours or more. So I could go on nearly as long as The Warp just on my own, you see.

I'm not a stand-up comedian. I'm probably a sit-down tragedian and a humorist. As subject matter goes, I'm really only interested in the remote, the remarkable, the weird, the odd, and out-of-the-normal run of things.

What are your plans for the future?

I'd like to do some more interviewing jobs for the box. I did a programme a couple of years ago called Reality on the Rocks, where I represented the ignorance of the British viewer in the world of quantum mechanics. I interviewed Stephen Hawking and went to investigate the experiment in Seame and some other stuff. I really enjoy doing those things. I've got three weeks at the Edinburgh Festival doing my own show. It'll last an hour at the Komedia venue. The National Theatre have also commissioned me to do a show. When I say a show, I just mean mainly me prattling at the audience. The working title of this is The History of Comedy. I don't know quite what I mean by that going back to the caveman, or maybe going back to the Big Bang, a kind of 'Brief History of Comedy’. I mean, the creation of the universe may well have been a joke, but in poor taste.

How did the show Pidgin Macbeth come about?

I went to the South Pacific, to little Tana Island, which is part of the Republic of Vanuatu. I went there to meet a tribe who worship the Duke of Edinburgh. That's where I got fully to grips with the lingua franca of the South Pacific. The language came about through slaves in about 1862. The interesting thing about the cannibal tribes, of the South Pacific anyway, is that every one of them has got an utterly different language, so that they are completely closed-in. Anyway, for slave-management purposes, it made them ideal, because you can fill a mighty plantation with these geezers and nobody can talk to each other. Eventually though, the slaves cracked how to communicate with each other. They listened to the guards. The language being spoken was kind of English, but as spoken by Irishmen. So the slaves listened to this Irish street slang and put together a mode of talking to each other that got known as 'plantation talk' or Pidgin English. So now the tribes could talk to each other by using this incredibly simplified Irish-English. It has got virtually no grammar. The tenses and verbs can be taught in sixteen seconds. There are no subjunctives, no passive tense, two prepositions and so on. I learnt the whole language in an afternoon. Now I run courses in Pidgin. It occurred to me that it's a bit silly that the world hasn't got a simple language, whereby everybody in the world can talk, in some simple way, to everyone else. So to begin my alerting of the world to this concept, I translated Macbeth into it.

Ken Campbell runs courses in Pidgin, Ventriloquism, and plans to run a course for women in Male Impersonation.