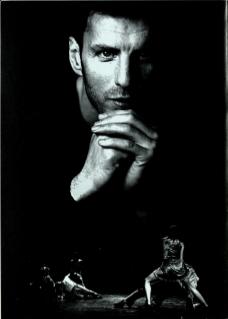

Since the inception of his company Ultima Vez in 1987, Wim Vandekeybus has left an indelible mark on the development of physical theatre. The work of Ultima Vez has become synonymous with a very specific vein of physical theatre coming from Europe. One that is committed to full theatricality accompanied by a movement style which is based on physical risk.

Vandekeybus came to dance from an eclectic artistic background. He is not only a choreographer, but an actor, dancer and photographer who trained with Jan Fabre (a collaborator of Robert Wilson) before establishing the company. Over the last eleven years he has produced annual projects in collaboration with Ultima Vez and various films based on the material from previous stage pieces. He also coordinated the musical composition The Weight of the Hand (1990) and more recently directed the theatre piece Alle Grosen Decken Sich Zu (1995). Vandekeybus' work is devised in close association with his collaborators, which include not only the dancers but also musicians like Thierry de Mey, Peter Vermeersch and Charo Calvo, designers and directors like Fabre.

The impact of the company on the international dance scene was immediate. In 1988 Vandekeybus received the coveted New York Bessie Award for his production of What the Body Does Not Remember. The production was very different from the expressive style of German 'tanztheater' and the socio-political themes of the UK company DV8; although comparisons between all three are inevitable. Vandekeybus is more interested in the experiential body than in forms associated with a codified dance technique, and with issues of perception through time and space. At a very immediate level the work centres around a physical image which creates a particular sense-perception. For instance the weight and sound of concrete bricks in What the Body Does Not Remember, the sound of floor tiles shifting in Bearers of Bad News, dirt and nude male bodies in Mountains Made of Barking. The work is characterised by shifts between live performance, film and soundtrack. However, it is the movement aspect which, in conjunction with the sensual images, weave a complex tapestry.

Speaking before the performance of the latest piece 7 For A Secret Never to be Told at the Oxford Playhouse, Rasmus Olme, a long-time company member, spoke of Vandekeybus' interest in the theatricality of movement and his constant investigation of how movement (and in his particular case, movement from a variety of sources) operates within a theatrical context. Olme identified certain recurrent focuses in Vandekeybus' work, among them the notion of exhaustion, infinite repetition with variations of context and the sense of the dancers being 'on edge’. The impact of the work stems from its 'reality'. The dancers take real risks, only just avoiding possible crashes and falls in potentially neck-breaking movements. The sound of their panting breath on stage gives evidence to the physical demands of the material. Watching the work, the dancers appear to be controlled by intangible hidden rules. There seems to be an underlying structure of play which organises the various exchanges and the connections between scenes. The play sometimes becomes the essence of the work itself and often has no specific end and resolution. It is this feature which is most satisfying about Vandekeybus' work; the performance sustains a sense of play ad infinitum.

For Olme, 7 For A Secret presented a challenge in many ways. The creative process demands great commitment from the dancers. They are asked not only to improvise in text, song and movement but also for the latest piece, for instance, to carefully study the behaviour of magpies, discuss the films of Starewitch, Tarkowski and Altman, and the texts of Theocritus, Camus, Octavio Paz, Brecht and Bachelard. Vandekeybus does not require his dancers to be simply 'technical machines'. In the performance each dancer ‘carries' a scene and, for Olme, this represented the biggest challenge and also the highest sense of accomplishment. For the audience, 7 For A Secret evolves in a constant flux between challenge and wonderment. We are challenged to witness the exhaustive repetition of material which Vandekeybus purposely wants us to watch and watch again with only the tiniest variation.

The piece, although based on the well known rhyme, is not just about superstition; it is more of a journey into the darker side of human consciousness. The beauty of the work lies precisely in the fact that you can never pin down exactly what it means. The stage is a dark cavern, peopled by lost souls, with brief explosions of light which allow the audience to watch a dazzling female quartet. The full body movement associated with Vandekeybus' work is re-articulated into the fast motion of individual body parts delineating pathways of energies tensely contained within the female forms – hip to head, chest wide open, ribs reverberating. There are repeated themes from previous pieces, here manipulated anew. Vandekeybus' vocabulary is no longer limited to solo work or the brief one-to-one encounters of Mountains and What the Body Does Not Remember. In 7 For A Secret, the vocabulary is orchestrated to generate encounters within trios. At times there are elaborate spatial exchanges between the whole group; these are negotiated within a stage which is an obstacle course of gigantic feathers which hang from the ceiling and pierce the floor to form a visible boundary which encloses the dancers.

Vandekeybus is constantly aware that theatre is a place of encounters – between the dancers, between the dancer and the music and the audience, for instance. These encounters create complex relationships which are not just limited to that which is perceived on stage. The events generate hundreds of parallel narratives in each and every one who comes face to face with the work.