The key to the concept of Tambours sur la Digue ('Drums Above the Dyke’), written by Hélène Cixous and realised, in collaboration with the company, by Ariane Mnouchkine, comes after three and a half hours, when we think the end of the epic has come and gone and the house erupts in a frenzy of applause. The performers – all but two stripped of their masks and costumes – leap onto the stage for their bows, retiring and returning again and again. But in front of them chest high in the deep water at the centre of the stage, the Old Puppet-Master remains – masked, hatted and immobile – with a hooded puppeteer behind him. After the fourth or fifth return of the actors, he and his operator climb slowly out of the water, and solemnly he bows to the rest of the cast, who bow in return, acknowledging his supremacy and control.

Mnouchkine received the Molière prize, the most prestigious France can offer, for Tambours sur la Digue. It is an elaborately staged play, densely scripted. Mnouchkine, says Cixous (a regular co-worker), asked her to write 'an ancient piece that could have been written by Hsi-Xhou the poet, sometimes performed by puppets, sometimes by actors'. There followed extensive research in the Far East, when the author felt that the master-puppeteer Hsi-Xhou was with her, setting the imagination of the author puppet in motion. The result is a fast moving tale which may be received by the spectator on many different levels, with multiple layers of meanings and timeless resonances.

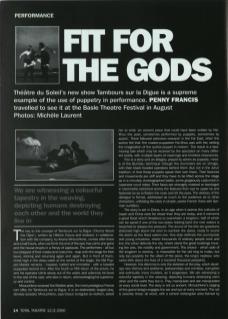

This is a story and an allegory, played by actors as puppets, mostly of the Bunraku technique (though the drummers are on strings), with their black-hooded operators behind them (but not in the Jorun tradition, in that these puppets speak their own lines). Their features and movements are stiff and they have to be lifted across the stage as in a minutely choreographed ballet, some gorgeously costumed in Japanese court robes. Their faces are strangely masked or bandaged in stockinette stretched across the features from eye to upper lip and fastened so as to flatten the nose and tilt the eyes. The delivery of the dialogue is formal, addressed as much to the audience as to other characters, unfolding the story in simple, poetic French (here with German surtitles).

The story is set in China, in an age when it seems the cultures of Japan and China were far closer than they are today, and it concerns a great flood which threatens to overwhelm a kingdom, half of which can be saved if one of the two dykes holding back the river waters is breached to release the pressure. The drums of the title are guardians stationed high above the land to overlook the dykes, ready to sound the alarm as the flood waters rise. One dyke defends the countryside and young industries, where thousands of ordinary people work and live; the other defends the city, where stand the great buildings housing the arts, the nobility and government. The choice – which side of the kingdom to destroy – is impossible for the old king to make, but only too possible for the villain of the piece, the king's nephew, who cares little about the lives of a hundred thousand peasants.

However, this dilemma is only the skeleton of the play, which develops new themes and problems, partisanships and enmities, corruption and eventually many murders, as it progresses. We are witnessing a colourful tapestry in the weaving, depicting humans destroying each other and the world they live in. They manipulate and are manipulated at every social level. The story is not so ancient. Mnouchkine's staging of this grand design engages the ear and eye at every moment. The set is severely linear, all wood, with a central rectangular area framed by stones and intersected by boards, with ramps and steps on different levels serving as plains, rivers, mountains. Behind, covering the vast back wall of the Reithalle, towers a silk cloth which gracefully flutters to earth at every scene-change to reveal another and then another, each subtly different, usually undecorated, but sometimes minimally painted in the Chinese manner with shadowy trees and hills.

The effect is beautiful. We watched from steeply tiered, end-on seating imported with the show from the Cartoucherie near Paris, the company's home. The performers numbered about twenty-six, variable in quality of voice and movement. The story is embedded in the words, so clarity and strength of tone is essential, and weaknesses in projection threatened our understanding of the plot, especially in so large a theatre and against the almost constant music from Jean-Jacques Lemétre. The demands on the actors of physical flexibility and control were also great, and most notably he who played the Chancellor (Ducio Bellugi Vannuccini), exhibited all the attributes of what Gordon Craig must have meant by his über-marionette, his vision of the supreme actor 'plus fire minus egoism'. Many of these performers would have won his approval, for they appeared not to be flesh and blood but bodies in trance.

This was theatre fit for the gods, but essentially a theatre for Everyman, for the punters once high in the 'gods' or down in the pit. Mnouchkine would have intended that.