The Old Operating Theatre Museum is one of London's more gruesome interiors. Dating back to 1822 it is the oldest surviving building of its kind. From 21 May to 1 June 1996, in addition to housing an eye-watering collection of arcane surgical instruments, it played host to The Resurrectionists' first show: Vesalius – A Requiem.

In 1543 Andreas Vesalius published De Corporis Humani Fabrica, thus earning himself the moniker 'The Father of Modern Anatomy'. Prior to Vesalius, dissection was the preserve of Barber Surgeons, men whose primary qualification was a swiftness with the blade. Vesalius' science was rooted in observation and description, making him a seminal figure in our conception of scientific enquiry as a whole. Hitherto medical science concerned itself with demonstrating and proving the theories of the great classical scientist Galen. Vesalius' willingness to adopt new ideas not only made him an important Renaissance figure but also brought him into conflict with the Catholic Church, the dominant ideology of the day.

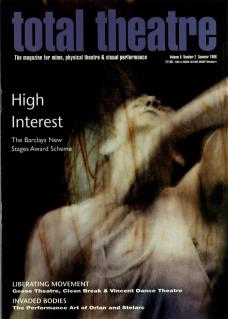

I met with core Resurrectionists' Graeme Rose (performer), Alan Hay (writer), Richard Chew (composer) and director Henk Schut to discuss their Barclays New Stages award winning Vesalius – A Requiem. Firstly what was it about the 16th Century surgeon that excited their theatrical imagination?

‘There was a clear element of theatre in Vesalius' work,’ Alan says. ‘He gave extraordinary demonstrations which already had a theatrical quality to them. It's not as if we needed to invent that aspect too much.’ Indeed the frontispiece of De Corporis Humani Fabrica is an engraving of one of Vesalius' open air demonstrations, and around the operating table the illustration shows the most tremendous crush of spectators (not to mention dogs and a monkey!). ‘We also wished to explore how much the experience of death has been lost to us,’ elaborates Graeme. ‘There is a whole industry that kicks in when a person dies. somebody takes the body to the mortuary, somebody else deals with it, etc. The family may have no part until the funeral service. Very few people have even seen a dead body and yet the urge to stare at death is still very strong; we watch gory movies or hospital documentaries for example.’

‘Pathology is the new Rock 'n’ Roll,’ says Alan with a flourish. It is? ‘It is,’ he insists, ‘there's that programme about the female pathologist, endless Silence of the Lambs type movies, album cover art... whatever. These fascinations are going round in the culture and this particular package of ideas' place in that culture.’ Alan continues, coming back to Vesalius – A Requiem, ‘It is an examination of the nature of enquiry – we uncover the life of Vesalius and in doing that we uncover Vesalius uncovering the human body, and all this is done within the context of theatre, which is in itself a form of enquiry. Everything looks in on everything else.’

So why a requiem? Richard says, ‘I thought in writing music about a Renaissance figure it was important to address the music of the time, therefore you are necessarily talking about religious music. At the time Vesalius was working, the Requiem as a strict form came into being. In the early 16th Century the Council of Trent prescribed the form of the Requiem Mass. In the show the music may or may not be heard filtering through from old St Thomas' church (directly below the Old Operating Theatre), and so the music's relation to the stage action is ambiguous. There is a distance, an irony to this Requiem Mass, which is intentional.’

‘The sense of resolution in a requiem mass is rhythmically appropriate to the text and performance, we borrow something of its tone, something of the manner in which it addresses its subject, but we are not necessarily adopting the metaphysical aspect. This isn't in any way a religious show. Furthermore, in any piece that's not a well-made naturalistic drama, there is a problem in allowing a character to just speak into open air, let alone sing! But one of the strengths of this form is that speech, movement and song are built into it.’

Chekhov, exasperated by Stanislavski's pursuit of realism wrote, ‘There is a genre painting... in which the faces are painted marvellously. What if you were to cut out the painted nose and put in a living one? The nose would be 'real', but the picture would be a mess.’ Did they not fear that the realness of the ancient surgery would swamp the fictional account of this ancient surgeon? ‘We play with that,’ Henk Schut explains. ‘That conflict between reality and fiction, that is a very important element of the show. We love working here.’

In order to counteract the danger that Vesalius – A Requiem could have been regarded as a museum show intended to educate, theatre-maker Chris Heighes created an installation in another part of the museum.

The installation was a living, mysterious exploration of its own, standing in oblique relation to the requiem. In addition to charging the arguably arid atmosphere of the museum, it functioned as an ante-room to the Resurrectionists' show, since it was impossible to see the show without first passing through Heighes contribution.

Given then, that Vesalius – A Requiem is neither a biography of the anatomist, nor a history of surgery, what is it concerned with? ‘Chiefly it's a celebration of life, any life. It's a statement about existence,’ Graeme begins. ‘Physical human presence,’ continues Alan with emphasis, ‘and hermeneutics [that's the science of interpretation for those of you who, like me, don't know] and also just the sheer joy of looking at the human body!’ A hymn to humanness if you will?

‘Yes I think its very much a life-affirming piece,’ says Richard. ‘Despite being set in a mortuary it is a celebration of life.’

It is striking the number of dialectics the show embraces: a secular mass, a celebration of life centering around the mortician’s slab, a real-life (albeit old) operating theatre as the set for a fiction and on and on... ‘That,’ Henk says simply, ‘is theatre.’