Para active have created four productions to date, all devised. Our process is derived from the tradition of actor training created by Grotowski and from explorations in the areas of rhythm and song. Each production takes between nine and eighteen months to complete; a process that includes making various versions of the show with different performers and building up a thickly textured performance from each of the different phases. I collaborate with Jade Maravala, actor and assistant director, on all our productions. In the future our goal is to find a core ensemble of performers to carry the work through all its phases. But, as the acting profession in the UK is project based, we have found it difficult to get people to commit to a long-term training schedule. This is partially due to the long hours involved and lack of money, but also to do with the general attitude to training. It is simply not possible to find performers who are musical and able to act, dance and sing. We need actors who can do all these things, but who can also go beyond themselves and transcend their own abilities.

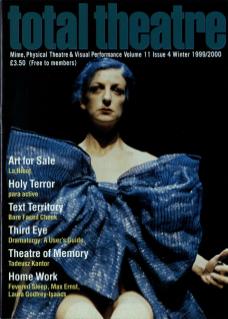

Holy Terror is a show about terrorism. The piece was conceived as an adaptation of Robert Irwin's novel The Mysteries of Algiers. After being refused the rights to adapt the book, it remained nonetheless as an inspiration. The novel is about the Algerian war of independence and the fight against the French. I was obsessed with the protagonist, a brainwashed terrorist. He seemed to me to be a psychopathic version of an actor, a performer of extreme and devastating acts against society. I believe that art should approach taboo subjects, often from angles that are morally dubious. Our approach is to work on the level of imagination and to not subscribe to any prevailing notions of morality. Our intention in Holy Terror is to pursue the archetypes and common values that surround our communal experience of violent protest and to discover a structure for a modern myth.

One occasionally regrets the devised process. I have no idea how other people do it. The phrase ‘devised theatre' sounds cheap to me, amateurish – a working method not given the status of a proper artwork. When speaking to potential performers, some tell me they are good at 'devised theatre'. What do they mean by this? Are we coming from the same place? Forced Entertainment and Derevo both create devised work, but para active have nothing in common with them. To me, approach is a question of training – that will dictate the performance style.

The audition process begins. Our audition exercises are designed to really test the performers. Steven Egan assists us in developing our training and running auditions. He is attuned to, and interested in, the kind of work that we do and is the other main collaborator in the project. If our work is to be a success, we have to find the right performers. After a month of auditions we find eight performers: Kerrie, Sachiko and Veejay are recent graduates, Eileen and Sebastian are older group members, and Shona has recently completed teacher training. It is a mixed group with at least six different nationalities.

The first scene we work on is based on an the Irish rebel song, 'Patriot Game', whose sentiments are anti-British and nationalistic. Nationalism is at the root of many terrorist causes. We set the lyric to a capoeira song from the popular Brazilian martial art. I have taken the circle from capoeira (the roda) – where combatants enter in pairs and fight – and combined it with Peter Brook's improvisation circle, to create a game. Capoeira is a fight, a game and a dance. I have used it as a device to help prepare the performers. The Patriot Game is about the struggle for liberation: a game played out between terrorists. It is representative of the coming fight.

A week goes by and I'm already worried that it's not working out. There are complaints: every day someone is ill or injured, we rarely start rehearsals with a full group. We talk with them about discipline, punctuality, respect for the space, the speed of work, listening and being sharper. Had we time for training, these sorts of problems would not occur. It is the beginning of the conflict between their habits and our idealism.

The second phase of work is based on physical action. The meaning of this phrase, derived originally from Stanislavski, has been developed by Grotowski and Eugenio Barba. It is the precise and formalistic externalisation of an interior process where the performers develop action through focusing on their personal research into their characters. We will be working through the elements of a system of training that I learnt from Jolanta Cyncutis from Grotowski's 2nd Laboratory Theatre of Wroclaw. The work puts the impulses of the body into a flow of movement via rotations borrowed, I guess, from Decroux. I use it to try and open the floodgates of the imagination in order to help the performers develop spontaneous action for scenes that are based on their research into the various terrorists they are interested in. There are a variety of influences: the Muslim Brides of Blood, the North Korean government agent Miss Kim, a strange cartoon character based on Lara Croft. One has to assume that locked inside the performer is their performance; the technique is a baited trap that draws it out of them. What I am looking for is the body as an externalisation of the imagination. That means the performers' bodies must react – with no distance between thought and action. It is a sort of Holy Grail to find real improvisation.

I am interested in the eroticisation of weaponry – chicks with guns, guns and saris, the hypersexuality of the woman and her relationship to her weapon

It is very difficult to be lucid about a process that requires immediacy rather than reflection. We are under pressure to complete and already it feels as if we are running out of time. I am smoking and drinking like a sailor; there is no end to my concentration and my ideas and no beginning to my organisation.

The reality is that Jade makes everything possible. She performs, administrates, leads the training and keeps discipline; she is hard and doesn't take any shit. She keeps us from drowning,

The work on action goes a different way than I imagined: some of the cast, like Jade and Shona and Sachiko create complete scenes; some, like Steve, make a line of action. From Jade's work on the intifada, an entire section arises which we call 'The Uprising'. It is seemingly chaotic, with different languages and a mass of movement. But it is organised spatially and vocally, with a haunting melody crossing it all. The 'Training Camp’ is the next section to emerge. I create a phoney Kata, a martial art form based on tai chi, capoeira and kung-fu. Central to it is the stick fighting that we use in the training to improve reflexes. It is our common language. Halfway through the show these disparate rebels gather and choose war. We use the Kata as our theatrical language for war. It is a discipline that the performers must learn and which they use to create subsequent scenes. It is a celebration of violence, a way of making death and killing acceptable. From this point on we take up arms.

Jade has found our stage manager Richard and our lighting designer, Joe. Richard is very down to earth and practical and Joe is a workaholic, a non-stop lighting and design guy – just what we need. Thank God.

Most of the actors are female. We haven't tried to over-emphasise this, but I am interested in the eroticisation of weaponry – chicks with guns, guns and saris, the hyper-sexuality of the woman and her relationship to her weapon. There is something attractive about doing what is expected, exploiting the sexuality of the women. We have plenty of images of eroticised violence performed by women for the pleasure of men. And no good ever comes of it.

We do a work-in-progress performance for friends. Their comments are critical but I hope not discouraging. Nevertheless, afterwards I feel that certain rules needed to be established. To destroy the mediocre, we must try and reach certain standards. Before our first rehearsal at Three Mills Island Studios I give the following notes:

i. Always look for a new improvisation to develop a structure.

ii. When we have a structure, keep to it and look for more details.

iii. Work at all times.

iv. You are always on the stage.

v. Always remain in a state of action.

vi. ‘Passive in action and active in look' (Grotowski) – when you are working remain open to other stimuli on the stage, when you are still remain aware and ready to respond.

vii. The rehearsal is a performance; you must give no less energy in rehearsal than you give in performance

viii. You must know what it is to excel, to go beyond yourself. If you do not know this, when you perform you will be lost. You must know what it is to be extreme.

ix. Every good actor knows how to contain what they are doing whilst simultaneously operating night at the edge of their energy

Jade has performed the next miracle and found two capoeira percussionists, to join us, Marcus and Aswani. Now we have the Birimbau and a bass drum. Nothing could change the feel of the piece more – suddenly the rhythm of the songs is really alive. We just need an audience now.

There seems to be a lot of illness at the moment, unfortunately the whole group suffers, weakening the energy. I fear the sink into mediocrity: mediocrity and self-satisfaction wholly and absolutely repulse me. I prefer performers who confront themselves, every day working hard to push through their personal blocks. This is where I take my idealism from Grotowski: a search for something new each time, the extermination of mechanical repetition, confrontation.

The show is finally coming to completion and I am finding myself becoming more and more involved in the practicalities – dealing with lights, sound, set and costumes, licensing. We have a show which, when I reflect on it, does not appear to be about terrorism at all, although it is quite clearly about the decision to take up arms in violent protest. Instead it is about the condition of conflict – idealised visions of it, received images of terror. And in the end we have dispensed with narrative, foregone the temptation of dramatic conflict and given emphasis to ritual. We have created communal songs which sanitise violence and repressive attitudes through euphemism. I would like to express the thrill of the opening night, but I still feel the knife edge as we run through the lighting cues twenty minutes before opening. The actors feel the thrill, I can tell by their faces afterwards: a mixture of relief and pride. But for myself – gaffering down cables until the last minute and still giving sound cues during the show – it is different. Suddenly I have a role like Kantor: I am onstage with the cast – operating the puppet, singing, wandering around the space. It feels natural but it has no precedent. It was probably what I was meant to do all along.