In the beautiful Renaissance town of Périgueux in the Dordogne region of France, Marcel Marceau created his best-known and best-loved persona, Bip.

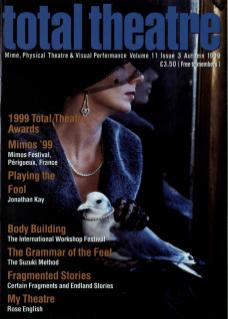

It is appropriate, then, that Périgueux should host Mimos – one of the few festivals in Europe devoted entirely to mime. White faces and stripy jumpers, however, are consigned to history. It is the avowed intention of Peter Bu, the festival's artistic director for thirteen years, that Mimos should demonstrate the quality and diversity of contemporary mime.

Over the course of a week in August, Mimos 99 saw some nineteen companies from all over the world present their work. British mime was well represented with Nola Rae, Compagnie Dust, London-based artist La Ribot and street theatre company Strangelings all performing. There was also work from Canada, Germany, Spain, America, Austria, Holland, the Czech Republic and France. In addition to all this, each morning the town's picturesque Place St. Louis played host to daily meetings between performers and journalists. It was all very civilised. Over breakfast the artists were introduced to the assembled press pack. Polite questions were met with polite answers, and whilst one may have wished for a more stimulating debate, it was an undeniably pleasant (if rather quaint) way to start the day.

These same journalists formed the 'Jury de Press' and the week ended with the presentation of the 'Prix de la Critique'. This year it was awarded to La Ribot (aka Maria José Ribot) for her show Encore Plus Distinguées. It was a just decision. Mimos 99 aimed to celebrate the body and answer the question: What does the body say that words cannot? La Ribot's show was unquestionably rigorous in its examination of the body and its possibilities. Her work exists somewhere between mime and dance, and Mimos demonstrates the riches this sort of cross-pollination can produce.

Catalan mimes Xavier Marti and Christian Atanasiu created a rich black comedy in their show Inuit, l'Humour Noir des Hommes Gris. Marti and Atanasiu have been together for some nine years and although the sketches that make up their show are very funny, they always maintain a dark edge. Indeed, in the course of their mise-en-scene, they will often abandon ideas that they deem merely funny. It is not always easy for them to explain this aesthetic – this balance between light and dark – to the directors they invite to help shape a show once the initial devising process is complete.

Perhaps the most unusual working process of any of the performers present at Mimos 99 is that shared by Sue Arnold and Brenda Wait of Compagnie Dust. Brenda is based in Bristol whilst Sue lives in Australia. They too use an outside director, but much of the devising process is done during expensive long-distance phone calls between continents. It is hard to imagine this being ideal, and it may explain the flaws in their show Poussière. The show introduces two characters that have supposedly lived for many years in the same room. They have created a series of rituals for themselves, to compensate for their lack of knowledge of the outside world. Central to these rituals are their Wild West fantasies.

It is a charming idea and some of that charm survives the show's rather muddy realisation. But there is little sense of the two characters having endured each other's company for years, and the relationship between the performers, the fourth wall, and the audience, is never properly resolved. Whether it was for this, the technical failings, or just a dislike of Wait and Arnold's deadpan humour, the show received a surprisingly hostile reception from the Périgueux audience on its opening night.

Peter Bu, Mimos's artistic director, had seen Compagnie Dust at the London International Mime Festival (where they had been warmly received), and was rather puzzled at the show's relative failure in Périgueux. By the second performance, however, technical glitches had been ironed out and Wait and Amold declared the show a success.

In contrast, one piece of theatre that enjoyed a rapturous reception was that of Canadian company Omnibus. Inspired by the court of the medieval queen of England and France, Eleanor of Aquitaine, their show La Flèche et la Coeur is made up of ten fragments exploring feudal ideals of allegiance, love and honour. The performance is of an incredibly high standard and the music, played on period instruments by Sylvie Grenier, is undeniably beautiful. Yet, despite the audience's enthusiasm, this visual poem seemed rather dated. It came as no surprise to learn that the show was over ten years old and is no longer really representative of the company's work.

The other unqualified success of Mimos 99 was the closing show by self-styled eccentric Avner Eisenberg, an American clown-mime. Eisenberg was a student of Jacques Lecoq. Initially he practiced his art as a street theatre performer. Indeed, in 1971 he was arrested by the Gendarmes and charged with buffoonery in a public place. Eisenberg is now more frequently seen in conventional theatre spaces and usually bills himself as 'Eisenberg the Eccentric' – preferring to downplay his mime background.

As he explained to the press in Périgueux, Eisenberg feels that had he called himself a mime, his career would have been over before it began. If his show Exceptions to Gravity is anything to go by, whatever he calls himself, Eisenberg's skill of holding an audience remains undimmed. Like at so many of the festival's shows, the theatre was packed, but Eisenberg unquestionably drew the widest audience, and there is little doubt that had the public awarded a prize Eisenberg would have won it.

The programme for Mimos 99 promised that the streets and squares of Périgueux would be ablaze with comedy and outlandish surprises. What little street theatre there was, however, was for the most part moribund and unmemorable fare. In truth, outside of its theatres – and despite the Herculean efforts of the marketing team – Périgueux itself seemed untouched by the festival. Some of the larger outdoor shows were disrupted by unseasonably stormy weather, but nevertheless it was impossible to escape the sense that Mimos is somewhat detached from the town.

One of the great joys of the Edinburgh Festival, for instance, is the access to that city's cellars, lodges and classrooms that festival-goers enjoy. At its best the London International Festival of Theatre will drag the would-be audience member to parts of the city into which they may never have hitherto ventured. A good festival unwraps and illuminates its host city. Mimos, despite the unquestionable integrity of its artistic director, has something of the air of an added value attraction, a further enticement to visit this historic town.

Many of the press felt this year's festival was something of a let down. It was a polite, even conservative affair, and, in truth, one longed for a flash of giddying inspiration or danger. Mimos is the only mime festival in France and on this showing is unlikely to exorcise the spectre of Marceau's Bip which hangs over the form. Nevertheless there is much to applaud about the festival.

Peter Bu once wrote: ‘Mime differs from other kinds of theatre only in its predominant means of expression, that of gestures, attitudes and facial expression.’ (Gestes no 4, 1993.) Mimos is devoted to work of this nature. It is a tribute to all of those who worked on the festival, but particularly to Bu – whose fierce belief in this work drives it all – that practically all performances played to full houses.

The Mimos Festival International du Mime Actuel de Périgueux takes place every August in Périgueux, France.