So what's in a name? Visions is now ‘the festival of visual performance'. Is this an opportunist jumping-in to fill the space left by Battersea Arts Centre, who have replaced the British Festival of Visual Theatre with Octoberfest? Is it an attempt to move away from the tag of puppetry, as this is too often viewed as non-serious theatre for children? Or is it a challenge to theatre-makers and audiences to take on board the immense breadth of possibilities in the field of visual performance?

The answer is probably a little of all three. Regardless of BAC's reasons for knocking the BFVT festival on the head, there is no doubt that this is Visions' gain. Those interested in visual theatre need no longer dash up and down the M23 between the two, but can just pitch up in Brighton for ten days to experience the best national and international work. Being concentrated into a short period of time gives Visions the feel of a true festival – racing from venue to venue to catch shows; bumping into people from other parts of the country that you haven't seen in ages and seeing people of all sorts from the local community coming out to join in the fun. One characteristic of a true festival is that it engages the community it takes place in – it is something that people approve of and feel proud to have happening in their neighbourhood.

An example: Forkbeard Fantasy's Frankenstein played a sell-out four nights at Brighton's newly refurbished Corn Exchange. On the opening night, I bumped into dozens of people I knew – not just the usual crew of fellow artists and theatre fans that you'd expect but people that I knew from my children's school, family friends, neighbours. And this wasn't an exceptional occurrence – most of the Visions performances were full, and many of the people attending events weren't regular theatre-goers. Visions has obviously built on its established good record and pushed itself further into the consciousness of the local community

So what of the content of this year's festival? One concern about the name change was that it might open the door to such a broad range of work that puppetry would be sidelined. As it is such a neglected form, this would be a genuine worry as there would be even less opportunity to show work for theatre-makers using puppetry and animation. But fears were unfounded as many of the shows still fitted the previous brief of representing innovative puppetry and animated theatre. There were plenty of good shows for kids (this being half-term week) – from Meningen's beautiful interpretation of The Tin Soldier (shadows of tiny paper models and flickering lights on the walls of a snowy white dome) and Ding Theatre's whimsical Being a Bird, which had one of the best sets in the festival – a cross between a doll's house and a Victorian cabinet of curiosities, peopled by beautiful and batty birds of all sorts.

An aim of this year's Visions seemed to be to show puppetry as a vibrant form that could step outside of its conventions to work with other disciplines or be placed outside of regular theatre spaces. French company Les Locataires performed Fantasmagorie from the boot of their car. England's own Wireframe were commissioned to create Elevation, an installation and performance piece in Fabrica gallery (see p8). Anglo-Romanian company Theatre Insomnia showcased their new production Amalia using a Gypsy fortune teller's tent as its stage, and the cheeky walkabout booth of Castalet Portatif wooed passers-by with Pepe the puppet's singing and portrait painting.

Pepe and his hidden operator Daniel Raffel were voted the Best of the Fest by the Visions team of Young Consultants, a pack of 8 to 12 year olds who scurried round the festival doing workshops and seeing shows as part of their investigative brief. This scheme was one of the brainwaves of the Visions team, created in collaboration with Brighton and Hove Council Play Service... other councils and festivals take note!

One characteristic of a true festival is that it engages the community it takes place in – it is something that people approve of and feel proud to have happening in their neighbourhood.

There was also plenty of puppetry for adults: cabaret fun from Maybellene – the Living Fashion Doll, dark and dreamy images from Tram Theatre's Plume d'Ange and the extraordinary Israeli/German collaboration Children of the Beast, which explored the relationship between memory, truth and fiction in Holocaust survivors and the children of survivors.

But part of the remit for this year's festival was a desire to push the boundaries out a little more: to include work that wasn't based around puppetry or object animation, but which used technologies such as film and video in imaginative new ways; to bring artforms other than theatre into the festival and to encourage the investigation of new hybrids of forms and new ways of working.

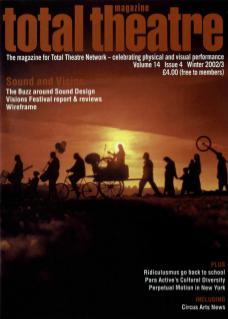

With the intention of approaching some of those desires and interests came the opening event of the festival: a symposium created in collaboration with Total Theatre Network and King Alfred's Winchester. Entitled 're:visions', it looked at the application of new media in live performance. Artists, academics and producers from a variety of visual and performing arts disciplines presented their personal visions and practical explorations.

Mat Adams from Blast Theory took us through the workings of a real live manhunt computer game acted out on the streets of Sheffield. Filmmaking collective Yeast showed us how they were re-inventing documentary and mixing it with live music performance. Holger Zschenderlein initiated us into the mysteries of sound sculpture. In a presentation straight out of an HG Wells novel, the professor and his prize student (graduate in the University of Brighton's BA Music with Visual Practice course Owain Rich) demonstrated a strange metal structure placed on top of buildings that read the weather elements of temperature, humidity and wind, data which, when fed into a computer programme, created an ever-changing soundscape.

A little closer to home (to those delegates with a theatre background) was Alex Hoare (a.k.a. Alex Shelton), a scenographer who presented a lyrical reflection on her artistic choices when working to integrate visual arts with performance. She was presented in virtual reality as a mouth on a screen, whorls of paint swirling round the moving lips. At the end of the presentation, she stepped out from behind the screen, her hands daubed with paint... a perfect way of showing rather than telling how such marriages of form can happen.

Jasmin Fitter from Random Dance showed how the company had transposed their own professional working practices into their extensive education programme – for example by teaching young people how to choreograph on computer regardless of their own dancing ability. Andy Lavender from Central School of Speech and Drama gave us a thought-provoking analysis of modernist, postmodern and contemporary approaches to new technologies in performance – examples shown included footage of such visual theatre luminaries as Robert Lepage.

But in their interest in the use of new media within theatre practice, these three presenters were the exception rather than the rule: many of the invited speakers seemed to uphold the current rather tedious orthodoxy that theatre as an artform wasn't particularly interesting, and that all the happening stuff occurred elsewhere...

This view was contradicted by the many shows in the Visions festival that were innovative and/or challenging despite being set within theatre boundaries. Australian company Igneous presented an autobiography in motion, The Body in Question. Using a variety of media (including film projected onto movable screens, projections superimposed on the performer's body and a life-size crash dummy) this was an exploration of dancer James Cunningham's relationship to his body before, during and after the motorcycle crash which left him with a paralysed arm.

Echoing Alex Hoare's presentation, Joan Baixas and Paca Rodrigo's Terra Prenyada placed live painting and performance together to create one of the most meaningful and visually beautiful works in the festival. A very different kettle of fish was Italian company Fanny and Alexander who presented Romeo and Juliet – Et Ultra. A deconstruction of Shakespeare's story of lost love, the production used torches, mirrors and a soundscape of distorted voice effects to batter the audience's senses. Although not a show that I enjoyed, I was interested in the festival's decision to include work that couldn't, under any stretch of the terminology, have fitted into any previous Visions festival programme. Nothing resembling puppetry or animation in sight!

Personally, I hope that Visions doesn't become too seduced by the lure of new technologies and continues to seek out the best of puppetry, animation and related forms to present – regardless of the media used, old or new. As was proved many times over in this festival, it is the artist not the tools that he or she chooses which is the most important factor. In the right hands, a piece of paper or a length of string can create images as powerful and mesmerising as any created by any other more hi-tech means. It's the vision that counts!

Following on from the revisions symposium, The User's Guide to New Media in Performance will be published in 2003. To register an interest, e-mail admin@totaltheatre.org.uk