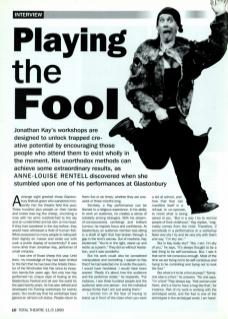

A strange sight greeted those Glastonbury festival-goers who wandered innocently into the theatre field this year: three hundred plus people on their hands and knees baa-ing like sheep, encircling a man with his arms outstretched to the sky and an unidentified animal skin on his head. If they had wandered in the day before, they would have witnessed a field of human fish. What possessed so many people to relinquish their dignity en masse and strike out with such a public display of eccentricity? It was none other than Jonathan Kay, performer of small miracles.

I was one of those sheep this year. Until then, my knowledge of Kay had been limited to the fact that he has been the Artistic Director of the Winchester Hat Fair since its inception twenty-five years ago. Not only has Kay performed his unique style of fooling at the Glastonbury Festival and all over the world for the past twenty years, he has also refined and developed his Fooling workshops for twenty years. You could say that his workshops have gained an almost cult status. People return to them five or six times, whether they are one week or three months long,

Similarly, a Kay performance can be likened to a religious experience. In his ability to work an audience, he creates a sense of solidarity among strangers. With his stream-of-consciousness ramblings and brilliant humour, he inspires focus and confidence. At Glastonbury, an audience member was sitting in a shaft of light that had broken through a gap in the tent's canvas. Out of nowhere, Kay exclaimed: ‘You're in the light, stand up and recite us a poem.’ They did so without hesitation, and it was wonderful.

But his work could also be considered manipulative and controlling. I explain to Kay that if he had selected me to recite the poem, I would have hesitated. I would have been scared. ‘Really it's about how the audience and the performer relate,’ he responds. ‘For instance, I see three hundred people and the audience sees one person but the individual always thinks that I am just seeing them.’

I remind him of the fear of having to stand up in front of the class when you were a kid at school, and how that fear can manifest itself in a refusal to cooperate, to resist what is being asked of you. ‘But in a way I try to remind people of their childhood,’ Kay replies, ‘originality comes from the child. Therefore, if somebody in a performance or a workshop feels very shy I try and be very shy with them and say, “I'm shy too.”’

But is Kay really shy? ‘Yes, I am. I'm shy of you,’ he says. ‘It's always thought to be a bad thing to be self-conscious. But, I see it that we're not conscious enough. Most of the time we are trying not to be self-conscious and trying to be controlling and trying not to look the fool.’

But what is it to be a fool anyway? ‘Someone else is a fool,’ he answers. ‘No one says, “I'm a fool!” They always say, “that woman over there, she's a fool to have a bag like that”, for instance. Part of my work is working with the archetypal world, and the fool is one of the archetypes in the archetypal world. I am handing myself over to an archetype. It is the foolish aspects of myself just speaking.’

All the same, Kay concedes that he can face resistance from his audience: ‘A lot of people think that I am a charlatan. Similarly, someone in a workshop may say, “I can tell you were against me.” I would say, “I'm not really against you, I'm just speaking into the present moment”, and the present moment is not somewhere that they might go very often. You are always in another moment, your considered moment. The idea is to bring the audience into the present moment. I try to help an audience discover the ability to be emotional, to capitulate to emotion. Emotion in this sense means that the more spontaneous you become, the more you're in the moment.’

Happiness is an ability to stand in your own house, on your own, and be content if you haven't got things to do, places to go, people to meet, things to fulfil, ambitions to ambition.

Is this the same as discovering how to be true to yourself? ‘Being true to yourself is a very interesting thing,’ Kay says, ‘It assumes the existence of two concepts – true to your self and true to something else. As if your self is something you want to be true to and it's sulking in a corner. So you discover a twin effect. Your twin is the “other”. That is, there's you and then there's somebody like you sitting just about there (he indicates a space over his shoulder) and the twin can be divided and sub-divided. So, you can have your mother and father there, sisters, brothers. If I asked you what your mother would think, you'd say, “Well, my mother would think...” Your mother's not here but you can talk to her. When you say she is here, where is she? So, as the fool, I'm saying to people don't believe that your twin belongs to someone else – it's you. That takes a long time to get to, and part of you – your twin – will resist that. But the other side of you will say yes to making up a poem or being a sheep in front of three hundred people.’

Kay's workshop practice centres on this twin effect. He has also used the relationship between fools and dictators as an extension of the twin: ‘It is the dictator in us that really forecasts what we do and how we do it. We allow dictators. One person is killed and you're a murderer. Kill fifty thousand and you're a conqueror. The dictator is basically the person who sits in the audience and the fool is the one that stands up in front of all those dictators. Nobody in their right mind would stand up in front of a bunch of dictators. But a fool would.’

Kay is dealing with big subjects. I imagine that a workshop with him would be an unrelenting process of self-discovery. Ben Owen, who is also currently documenting Kay's work on film, tells me: ‘I did a workshop six years ago and I've never recovered. There's a very strong reaction. Some people throw up, some people have nervous breakdowns, some people throw their cornflake bowl at their parents, some people think that it's all a load of rubbish, and some people cry for days on end.’

What happens with that emotion at the end of a workshop? Does Kay just send people back out into the world, or does he accept any responsibility for it?

‘I say that if they come up against something which they need to work on themselves, I encourage them to go and see somebody who can help them work out whatever it is that's come up as a result of the workshop. I also make myself available. They can phone me as well.’

Kay's latest venture is the Theatre of Now, a company he wants to develop with performers committed to his working practice: ‘People who want to work with the moment, who can use every aspect of themselves, reconcile themselves with their twin so they're happy, and then use that to then understand their audience.’

And what does Happiness mean to Kay? ‘Happiness is an ability to stand in your own house, on your own, and be content if you haven't got things to do, places to go, people to meet, things to fulfil, ambitions to ambition...’

When I met Jonathan Kay for this interview, he was smaller than I remembered. Gone was the animal on his head and the largesse of his stage presence. In its place was an unassuming man in jeans and jumper who is making it his life's work not simply to entertain but to challenge our own preconceptions of what it is to be human. Fool or charlatan, he is a man with a lot to say and contribute – not only to the performance world, but to the world in general.

Jonathan Kay can be seen performing at Smithy's Wine Bar, Leek St., London WC1 on 3 November and at the Lion and Unicorn Pub Theatre, 22-25 November.