Odin Theatre is a long walk from the station. It’s a really long walk.

Holstebro train station is a draughty Viking palace, and the commercial centre reminiscent of many small towns in Denmark, pedestrianised streets lined with recognisable stores, and punctuated by curious — sometimes striking — public art. Heading away from this hub, shop fronts quickly give way to residential streets and university buildings. Then garages, furniture shops. The ring road. Warehouses with less obvious functions. At some point on this trek I panic and call the theatre, convinced I am in the wrong place. But no; the warm voice on the telephone tells me to keep on going. For the rest of the walk I try to imagine the landscape of this unassuming conurbation when, 46 years ago, a troupe of young Norwegians arrived to set up their ideal theatre.

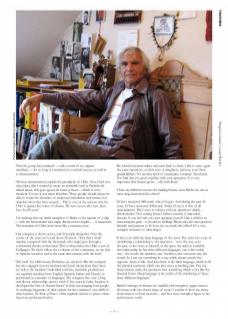

Eugenio Barba’s study recalls the cabin of a ship, slant-roofed and full of wood. The walls are decorated — like many of the Odin spaces — with photographs and postcards, beads, masks and hangings. They could be called souvenirs, but in this context they look more like treasure which Barba, tanned and compact as a sea captain, has accumulated on voyages around the world. Travelling, bartering and discovery all spring to mind when Odin is mentioned; part of its mythology. But what is going on in the here and now of a wet September afternoon, at the idiosyncratic Odin homestead?

‘At the moment we have the Odin Week, which,’ Barba explains, ‘is in reality about ten days. It’s for people who want to study the Odin; we gather them for this period. They are university teachers, theatre school teachers, scholars, researchers, actors, young people who are trying to find a sort of meaning in their existence’ — he smiles — ‘a real mixture. We take the first fifty who write to us, we don’t choose them.’

At the moment they are seeing a work demonstration by one of our actors. At four they will be seeing a performance which I made with an Afro-Brazilian actor, Augusto Omolú. After that we will be talking about how it is to work with actors from a different style, a different convention, and I will show a fragment from the Ur-Hamlet, where there were Balinese actors, Noh actors from Japan, Afro-Brazilian actors – about 50 actors from 25 different countries.’ The fragment turns out to be a short film which skilfully conveys something of the extraordinary Ur-Hamlet performance, made to mark the 50th anniversary of the foundation of Grotowski’s theatre laboratory. Performed at Ellsinore it is, as Barba describes, spectacularly ‘multicultural’ as well as epic and playful – towards the death-stricken end, with gold-clad courtiers and masked warriors littering the stage, a pile of bodies is quietly removed by a modern forklift truck.

‘In the evening,’ Barba continues, ‘the Odin Week participants watch the performances. In the morning they have training, so they get acquainted with some of the principles that we have been following, and each of the actors works with them individually… There isn’t one common training for everybody; each actor has been developing his or her own training. This is important to understand; that the training is autonomous, a style that an actor develops, that must be extremely personal.’

It is striking, in a collective with such longevity and renown, to hear about the individual; clearly the Odin is no communist bloc. But is it a community?

‘It’s a working community. We don’t live together, each of us is rather … individualistic, and with the years we have become even more individualistic. Most of us live in the country and come here. But we are a very strong working community.

‘It’s very important to understand the dynamics of a collective coming together for certain projects – like the International School of Theatre Anthropology – certain projects abroad, and at the same time individual projects, which can range from one man/woman performances — which makes them travel by themselves, autonomously, doing their own pedagogical activity — to big, big projects.’

And is this ‘collective’ integrated into the community of Holstebro? Barba confirms that Odin is ‘a deeply engaged community theatre’ – but admits that this was not always the case. In 1966, Holstebro boasted a mayor with progressive cultural policies, an empty farmhouse – and a resistant population. Barba tells the story of his company’s initial invitation to take up residence:

A local nurse, interested in theatre and a member of an amateur company, saw Barba and his actors perform in another town, and heard about their desire to move out of the capital (Oslo), and establish themselves in a small town. ‘She got so excited that she came back [to Holstebro] and called the mayor, whom she didn’t know.’ She suggested that they invite Barba’s company. ‘The mayor said, “well, call me in one hour’, and when she did he said “give me the address”.’

The group, uprooted from Norway, found itself in ‘a small town with no theatrical tradition. We moved from a capital to a place which was not only provincial but also backward… We had to teach ourselves, first; to establish a training for actors. People reacted very strongly because they couldn’t align all these strange exercises with the interpretation of Shakespeare or Ibsen.’

That the group has remained — with several of its original members — for so long is a testament to eventual success, as well as to determination.

‘All these circumstances explain the peculiarity of Odin. Also, I had very clear ideas, that I wanted to create an ensemble such as Stanislavski talked about, that goes against the nature of theatre – which is to be transient. For me it was more than that. These people should always be able to create the dynamics of reciprocal stimulation and remain, not abandon what they have created… This is one of the reasons why the Odin is against the nature of theatre. We have actors who have been here for 46 years.’

I’m realising that my initial metaphor of Barba as the captain of a ship — with the hermeticism and single direction that implies — is inaccurate. The members of Odin seem more like a castaway crew.

‘Our company is eleven actors, and 22 people altogether. Over the course of the years we’ve had about 50 actors. “Isn’t that a small number compared with the thousands who might pass through a commercial theatre in that time? This is what makes the Odin a sort of Galápagos. We don’t follow the evolution of the continents, we are able to separate ourselves and at the same time interact with the local.’

‘The local’ for Odin means Holstebro on one level. But the company has also engaged in more international ‘local’ interactions than most. As well as the members’ individual activities, ensemble productions are regularly translated into English, Spanish, Italian and French, or performed in a mixture of languages. The company has, over a long and diverse relationship, spent a total of five years in Latin America; it developed the idea of ‘theatre barter’ in Italy, encouraging local people to exchange fragments of their culture for the company’s own skills in what became The Book of Dances. Odin regularly returns to places where they have performed before.

‘We found interested milieu and went back to them. I like to meet again the same spectators, or their sons or daughters, and now even their grandchildren.’ It’s another kind of community, forming? ‘Absolutely. You find that you grow together with your spectators. It is very important that theatre grows…old, with them.’

There are different reasons for making theatre; does Barba see one as more important than the others?

‘I’d have answered differently when I began. And during the past 46 years, I’d have answered differently. Today I’d say it is first of all entertainment. But I want to achieve with my spectators simply… disorientation. Not scaring them; I believe security is important, because if you feel safe you start opening yourself. Like a child in an entertainment park – it should be thrilling.’ Barba asks the next question himself, and answers it: ‘So how do you reach this effect? It’s a very complex structure of subterfuges.’

‘It has to do with the deep language of the actor. The actor has a way of establishing a relationship to the spectator – or to the text, or to the past, to the story, to himself, or the space. In order to establish this relationship he has three different languages: one is the verbal one – the words, the narrative one. Another is the sonorous one, the sound. So I can say something in a way which means exactly the opposite. Irony is this. And then there is the third language, which is all the physical reactions; which can also stress something else. The way these interact make the spectators face something which is not like the classical forms. Deep language is the result of the interlacing of these three different languages.’

Barba’s writings on theatre are studded with metaphor: paper canoes; the house with two doors; ships of stone. I wonder if their use stems from interest or from necessity – and how does metaphor figure in his performance work?

‘Metaphor is the moment when you want to express an experience from reality and can’t use normal words. How can you express your passion for a woman, for a man, the fact that you are experiencing your existence in a very different way? How do you express… certain feelings. That you could kill someone?

‘Artistic language is a way of destroying language used in a simple way, and rebuilding it. It’s not that I like metaphor, but that it’s a necessity. When you refuse the normal way, it’s the only option. The poet is one who is recreating the language. If you want to recreate a situation on the stage, which has to do with reality or can be an imagined reality, you have to make use of metaphor.

‘This is especially true when you write. On stage, it’s different. Because we are animals and the part of the brain which deals with conceptual processes is, in fact, very limited. Much of the performance that I do is directed to other parts of the brain, which are not conceptual – just like music, like dance, seeing a landscape, listening to the waves breaking on the beach, watching snowflakes.’

In Theatre: Solitude, Craft, Revolt, Barba writes of ‘floating islands… that uncertain terrain which can disappear under your feet, but where personal limits can be overcome, and where encounters are possible’. The Danish archipelago; Odin as Galápagos; communities across the world linked by one performance; Prospero’s island; metaphor and reality interlaced, and a new language, still evolving.

Having recently visited the Barbican, London to participate in February’s HamletZar: Dissection conference, Odin will be performing SALT, The Flying Carpet, The Echo of Silence, and The Dead Brother in Taiwan 15–21 March before moving on to Costa Rica for the Festival Internacional de las Artes 2010 at the end of the month.

The company’s own Odin Week Festival, held in Holstebro, Denmark, takes place 12–21 August and is a ten-day intensive introduction to Odin’s training and working methods, as well as a festival of international performance. Deadline for applications is 29 June 2010.

Cassie Werber interviewed Eugenio Barba 25 September 2009.