‘One must embrace art to understand the essence of theatre. The growing "professionalism" of theatre destroys its essence, marking its "separateness". Theatre does not have its own, single unique source. (Its sources are in literature, drama, the visual arts, music, and architecture. All these arts "come to" rather than "come out of" theatre. And one more thing: [these arts] constitute the matter of the theatre. Let us try to discover the virtual ur-matter of theatre, its pure elements [which are] independent! autonomous!' – Tadeusz Kantor

It is ten years since the death of Tadeusz Kantor, yet his attempt to discover, together with his Cricot 2 company, the pure elements of theatre – as distinguishable, but inseparable, from those of other arts – remains exemplary of what one could call 'total theatre'. While his work has not yet received the recognition in the UK that, for example, the actor-based research of Grotowski has, its continuing hold over the imagination – even amongst those who never saw his work – poses the question not only of what we may learn about Kantor's theatre but also from it.

For not only did Kantor produce work of haunting power, but he continually reflected upon it, seeking to learn through each development. Each stage of his theatre was accompanied by a new manifesto: from the 'autonomous theatre' of 1956, through the ‘informel theatre' (1961), the 'zero theatre' (1963), 'theatre happening' (1967), the 'impossible theatre' (1969-73), the ‘theatre of death' (1975), and more besides, towards the last statements in, for example, 'a painting' (1990).

These manifestos offer a reading of Kantor's journey. In 1955, Kantor revived the pre-war Krakow artists' theatre group, the Cricot, instead of founding a new, professional theatre company. The informel period and the ‘happenings’ that Kantor staged through the Sixties reflect his involvement in modern art practice, situating his work within a wider European context, long before it became part of the international festival circuit in the late Seventies. It was a disappointment to Kantor that international recognition did not come earlier, at a time when these influences could have flowed both ways – East and West. By the late Seventies, when the Cricot 2 became a touring company, much of the early experimentalism had become conventional.

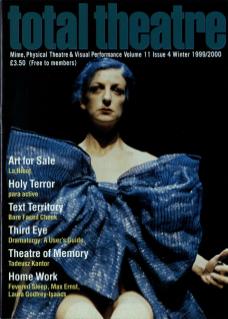

Nevertheless, it is for these later productions – The Dead Class and Wielopole, Wielopole, for example, that Kantor is most widely known in this country. And it is from these productions that we might try to extrapolate what it is that is unique about Kantor's theatre.

One of the most striking aspects of his theatre was Kantor's own presence on stage, playing the role of spectator within the productions, embodying the division between performer and audience, thereby making of it a protagonist. As he moved around the stage, reacting in different ways to what was happening, Kantor would occasionally address one of the actors, or indicate with a gesture for the music to become louder or quieter. He played a role identifiable neither with the actors nor the audience, but with the performance itself. Following his death, the Cricot 2 company soon ceased to perform, confirming that Kantor's work was in the discovery of it, and not in some version that could simply be replicated or represented, like a play with characters.

What each of these performances sought to demonstrate was a challenge to the seemingly inevitable reassertion on stage of theatrical illusion. Kantor wrote of his role, as it developed after the 1967 Cricot production of Witkiewicz's The Water Hen, 'When I see that an actor acts, when he leaves the plane of concrete reality... I come up and stay by him. It is enough to crush illusion because I am a spectator and not an actor... The director should be hidden, he is not needed on stage. But I stand there... destroy illusion since I appear on stage as if to say: I do not like that.'

This approach to the stage is expressed in the last word of the quotation with which this article begins – 'autonomous' – drawn from the opening of the Milano Lessons (twelve commentaries which Kantor wrote on work that he developed with students in Milan in 1986). For Kantor, theatre must be 'autonomous!' – comparable, but not subordinate to any other art (music, fine art, literature, architecture, etc). In principle, this appeal to autonomy is also a rejection of the predominant tradition of twentieth-century stagecraft – naturalism – and all that goes with it in terms of a certain professionalisation of theatre; from the essentially psychological (or interpretative) understanding of text and actor training, to the ever-growing affiliation between stage and screen (especially television).

It is, as the opening quotation insists, experiments within the history of art – as, for example, the Bauhaus – that Kantor embraces, before those in the history of theatre specifically. These tend to take for their subject, as their ‘basic element', the art of the actor (whether with Brecht or, perhaps more relevantly here, Meyerhold). Kantor's own work as a visual artist – in painting, sculpture, installations and Happenings – informed his discoveries in theatre more than those polemics within professional theatre, with their implicit reference back to Stanislavski.

Kantor's own contribution to the theory of the actor was to propose the mannequin as the actor's model. Where previous practitioners, like Craig and Schlemmer, looked to the form of the actor's movement within the theatre space, Kantor considered the actor as part of the material, the matter, of that space. What all these artists have in common, however, is a concern with what contrasts with the everyday, familiar experience of the living and the ‘natural'. The relation of theatre and art to its audience is thought of as evoking what people prefer to forget – the existence of death. It is to this encounter that Kantor's theatre returns.

The mannequin (a creature of fairgrounds and tailor's shops) took its place, with other 'poor objects', alongside the actor most famously in the late productions of The Dead Class (1975), Wielopole, Wielopole (1980) and I Shall Never Return (1988) – in which the theatre space became devoted to the staging of memory. The mannequin's presence is evoked in the fictions of the Polish-Jewish writer Bruno Schulz – from whom Kantor drew directly for The Dead Class. Schulz asks his reader to look at the mannequin anew: 'Can you imagine the pain, the dull imprisoned suffering, hewn into the matter of that dummy which does not know why it must be what it is, why it must remain in that forcibly imposed form which is no more than a parody?' Kantor presented this parody to the audience as in a mirror – it was the actor, when 'acting’, that seemed to him to become the parody.

Although Kantor refers his use of the mannequin again to art history – to the example of Duchamp’s 'ready mades’ – it was during the Nazi occupation of Poland (when Kantor organised an underground theatre) that he discovered for himself this basic element of his theatre. Of a production of Wyspianski's The Return of Ulysses in 1944, he writes: ‘The actors brought into the space the objects they had found: an old decayed wooden board, a cart wheel smeared with mud, parcels covered with dust, a soldier's uniform...’

These 'poor objects', as Kantor describes them, are taken from ‘the reality of the lowest rank'; they are 'annexed reality’, distinct from ‘fictitious or artistic reality’; not stage props put to the service of representing a reality existing elsewhere. Kantor proposes that these objects are on an equal footing with actors... The object ‘actor', as he would describe his actors.

This can be related to Schulz's description, in a story about mannequins (these doubles of the Kantorian actor), of matter's emergence into memory: ‘[The] Demiurge, that great master and artist, made matter invisible, made it disappear under the surface of life. We, on the contrary, love its creaking, its resistance, its clumsiness. We like to see behind each gesture, behind each move, its inertia, its heavy effort, its bearlike awkwardness.’ With Kantor, the matter of theatre, including the actor, reaches out from under its art and the performance emerges from illusion.

In staging the work of memory in such productions as The Dead Class, without the gloss of stage illusion, with nothing either simply decorative, or representational, of some other reality which could be truly recognised offstage, the encounter with Kantor's theatre realises Schulz's fictions. One can imagine the director quietly addressing those 'poor objects' at the start of rehearsals, with the following words of Schulz, thinking of the audience in the role of ‘the other person': 'Someone addresses you, makes a joke, pulls your leg, and you blossom forth for a moment. You rub up against somebody, attach your homelessness and nothingness to something alive and warm. The other person walks away and does not feel your burden, does not notice that he is carrying you on his shoulders, that like a parasite you cling momentarily to his life...'

Kantor made a theatre in which to experience the 'homelessness and nothingness’ of things (including texts), in which to remember rather than to forget oneself. Rather than being transported by illusion to some fictional place, we may find ourselves in such a theatre alive to the burden of the dead.