What is promenade theatre and where has it come from? Some theatre companies call the form Walkabout Theatre, fearing perhaps that the former title is highfalutin. However, as a dramaturg, I'm not sympathetic to such prejudices and will 'promenade’ on.

Ronald Blythe, writing in The Independent (1993) states: ‘The integrity of true theatrical communion can be an emblem of all our social relations at their deepest. It's no coincidence that we call a responsive audience “a good house”.’ But what constitutes an audience? Bums on seats?

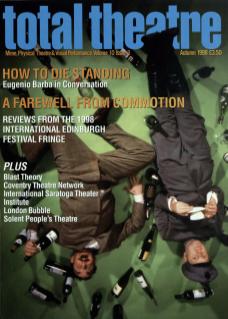

Promenade theatre appears to have no ‘house’ and rarely encourages its audience to sit, yet the quality of ‘theatrical communion' and intensity of audience response generated from this form is marvellous. Promenade has no difficulty generating sizeable audiences. In fact, The London Bubble Theatre Company has adopted the form for five summer seasons in a row, as it complies beautifully with the company's objective to provide ‘access to theatre, creating a popular theatre form which is open, exciting and accessible'.

The size of audiences visiting Williamson Park in Lancaster for their promenade season this year has swollen to an amazing five hundred a show. This summer, London has witnessed several highly successful promenade events. Jyll Bradley's Digging For Ladies, The Young Vic's Bone Room, La Fura Dels Baus' Manes, Theatre-rites’ Millworks and Paul Sirett's Jamaica House to name a few.

It isn't easy to discover the lineage of the Promenade form. Clearly we can look back to travelling artists and there are also connections with theatre in the round. The dictionary definition of promenade includes, 'a paved public walk'. I like this definition, as it captures beautifully the issue which is at stake in the form's use. How and with what should the walk be ‘paved', to best serve the audience? Where will the audience be moved and how will the movement be achieved?

The Spanish company, La Fura dels Baus, at Three Mills Island Studios as part of the Greenwich and Docklands Festival in July, motivate the audience to move out of fear. They treat their audience as if they are cattle to be hounded and prodded. Reduced to the state of livestock, the public are, as one Spanish critic noted, 'driven as much by the fascination of danger as they are by the instincts of trapped animals'.

To what extent must the audience themselves move for a performance to be qualified as a promenade? Does the turning of a head or the raising of a hand count as movement? And why would a theatre-maker want to make an audience move in the first place? Might they be merely looking for a device to avoid clumsy scene changes? Or, is the movement of the audience an underlying dynamic for the entire performance?

These are among the many questions I asked during my placement on the Writing and Moving project with The London Bubble Theatre Company over the last few months. The aim of the project was to find and develop writers who can harness the properties of the promenade form toward new theatre for contemporary audiences. Jonathan Petherbridge, Artistic Director of The Bubble, mounted the project because, as far as he could tell, most promenade productions originated from existing, rather than new, texts.

The Bubble commissioned three playwrights – Sharon Kennet, Michael Regnier and Louise Warren – to take part in an exploratory writing programme. The writers were joined by myself as dramaturg and Tony Craze, playwright and Writing Director for London Arts Board. We were all invited to follow the development of the Bubble's summer promenade performance, A Midsummer Night's Dream, directed by Jonathan Petherbridge.

As the Dream toured London, moving from one park to the next, the writers were encouraged to observe how the company responded and adapted to each site in rehearsal and performance. The design for this production played with symbols associated with sleep. Characters entered and exited the acting space on sumptuous beds with folding wings that were wheeled on by the fairies. Most of the company's problems were as a result of trying to navigate the terrain of the park on these beds. There was a lovely moment in the production where the audience passed alongside a series of sleeping tableaux. Unfortunately, during this sequence at Chiswick Park, one of the beds was positioned in such an arresting location that the audience formed around it and waited patiently for the sleeping form to stir. During this same performance, a performer took a wrong turn and became momentarily lost with hundreds of followers, amongst the trees.

Each of the three writers on the Bubble project were asked to present structures for short texts that utilised the findings of their research. It became clear during this first meeting that the process of each of the writers differed dramatically. We all had different expectations of what a script was.

On three brief occasions the writers collaborated with the director, the dramaturg, and the performers to explore means of realising their scripts. Jonathan Petherbridge collaborated with each of the writers on the direction and placing of their work, leaving room for further developments and explorations in the performance texts. On Wednesday 19 August, practitioners from across the sector were invited to the Horniman Gardens to participate in the Writing and Moving Open Laboratory. Our pieces were by no means polished, with the performers working with a script in hand, token props and costumes, and competition from the fork-lift trucks, irate park staff, and picnickers.

The audience was also cast as wild animals

The first experiment was Louise Warren's The English Park: A Murder Mystery. At the opening of this piece the audience was cast as a search party and fanned out across the park looking for clues. Louise made explicit use of the Horniman Park site as her script followed the mysterious trappings surrounding the life of Victorian explorer Horniman. Louise explains:

‘I wanted to explore time, and the mixing of times. So that we see Horniman himself out in the wilds of Africa; Lady Bench opening the gardens in 1912; and a modern day murder investigation. A criss-crossing of time and place. I wanted to make the moving itself [the promenade] the most interesting part, so that the arrivals are only part of the journey.’

There were beautiful moments during this piece, Lady Bench sported a white parasol with purple flowers, which she used to beckon the audience to follow her. The parasol, in turn, became the Purple Spottis butterfly that Horniman fanatically hunted down for his collection. The audience was also cast as wild animals, as Horniman backed towards us announcing the ‘strong feeling that a herd of wild beasts unknown are gathering at my rear'.

The second piece, Touched, by Sharon Kennet began with two performers in white coats resourcing the audience for Polaroid portraits and video footage. We were informed that a great woman who had lost a love was now seeking another. Labcoat-wearing love documenters then informed us that we had to make a decision. ‘There is a road through joy, there is a road through pain, only one will lead to love, you must choose.’ By exercising our right to choose, the audience were split fairly equally and separated to follow the espousals of one side of a love affair. At one instance the joy road sneakily intercepted the pain road, allowing this section of the audience to overhear the man's confession. There was a shrine-like configuration of photographs set up beneath a tree for the ‘joy riders' to discover.

By the time we came to the third experiment, Michael Regnier's Left, Right, and Centre, the audience was tired of walking. The performance began with a comical political debate, which resulted in the politicians summoning the audience to vote. We were to exercise our democratic rights by moving to the candidate of our choice. Funnily enough, a notable section of the audience tried to abstain. As this piece progressed the audience were broken into further factions, with some audience members declaring mutiny and running off through the bushes to join other groups. That's what happens when you empower the audience! Our experimentation had created a monster! Michael explained that his objectives were: ‘To experiment with providing the audience with an impulse to move, an impulse within the story being presented, to experiment with choice.’

My first encounter with promenade was as a child. Part of the pleasure in experiencing a promenade performance is exactly this recovery of a child-like perspective. Writer Laura Bridgeman observes of the form: ‘We return to the basics of exploration, magic, enchantment, discovery.’ Louise Warren and I testified to the strange manner in which powerful promenade performance has the ability to alter your perception of places and events for at least an hour after the show. As you make your way home from the show, everything is imbued with the potential to be engaging. Snatches of dialogue, discarded articles, and movement caught in the periphery of vision, are all potential leads into a series of dramatic events.

When I related my childhood antics to Simon Corble, Artistic director of The Midsommer Actors, he rejoined that the motivation for his work stemmed from a desire to interweave a childhood passion for exploring environments, playing and constructing outdoors, with theatre arts. Simon compared the promenade experience to that of a fairground ride, where a train of carriages moves through a fictional landscape.