Recently I was asked by a friend to act as an 'outside eye' for a production she was directing. After attending a rehearsal, I met up with her to give my thoughts. She invited me to attend another rehearsal and before long I was drawn into the production as both a sounding board for the director – with her vision of a highly physical interpretation – and an interpreter of an alternative view of the work held by some of the actors, who were uncomfortable with what they perceived as a move away from the writer's intentions.

No longer an 'outside eye', I was now more of an 'inner eye' on the work. And yet, at the end of the day, I walked away leaving the director with the final decision-making, so remained a little more detached from the work than either the director or the performers. Although not credited as such, my role in the production was as dramaturg – or at least the situation described above is an example of one of many possible roles that a dramaturg might fulfil.

After three days of artists' presentations, debate and practical workshops at the Dramaturgy: A User's Guide symposium in September, two things became clear: first, there are probably as many different interpretations of the role of the dramaturg as there are dramaturgs; and secondly, that not only theatre practitioners, but also performance artists, sculptors, composers and architects use a dramaturgical process in the creation of their work – regardless of whether it is acknowledged as such. As more than one delegate put it during the lunch or dinner break: 'So that's it then, I've been a dramaturg all this time and not known it.’

So what is dramaturgy? As Katalin Trencsenyi of Budapest's Academy of Drama and Film observed in the opening debate, it is easier to first sort out the function before looking at what it is that a dramaturg actually does. For although we can make a piece of theatre without a dramaturg, we cannot make it without dramaturgy. The most basic definition is that dramaturgy is the creation of drama. An oft-quoted definition is that it is the principle of dramatic composition. It is the art and science of theatre; the sum of all the processes of creating theatre and the theory that surrounds those processes. We can extend this definition to say that dramaturgy is the totality of all the elements that are contained in a performance or in a performative situation – the light, the sound, the spoken word, the experience of the surrounding space, etc.

Looking at it from the viewpoint of an artist creating a piece of theatre, dramaturgy is the process of taking a starting point which we can call the 'text' – this could be a written play, a concept or a site – and exploring the relationship of that text to other elements, to create a whole that is more than the sum of its parts. Even the most literary rendition of a pre-written play requires something to change it from that piece of writing to a performed text.

But what of other forms of theatre? An interesting question raised was the function of dramaturgy in physical theatre and visual performance where there is little or no spoken text. Moises Maicas of the Catalan company Comediants spoke of dramaturgy as the core of ideas and intuitions that are translated into tangible expression in his company's highly visual street theatre pieces. The notion of a balance between the elements of a performance was one that was reiterated many times and reflected in John Keefe's view that dramaturgy adds a third dimension that challenges the binary oppositions of intuition and intellect. This third way has been explored by many innovative theatre practitioners, from Artaud to Eugenio Barba, who have often been drawn to non-western forms of theatre that have a more holistic approach.

Although we can make a piece of theatre without a dramaturg, we cannot make it without dramaturgy

In his closing presentation, the renowned writer and director Clive Barker cited Barba as an example of someone who has promoted the notion of the actor as dramaturg to his or her own work, in contrast to the more grandiose dramaturgical collective that created the large-scale works of Max Reinhardt. The symposium also explored the function of dramaturgy in disciplines other than theatre. For composer David Toop, the dramaturgy of sound enables audiences to appreciate the sound world as a theatre of the imagination. Performance artist Anthony Howell and sculptor Randy Klein offered fascinating examples from their work of very different dramaturgical approaches. In essence, their work is diametrically opposed. Anthony Howell proposes an art that deconstructs text in an attempt to subvert the horizontal and the illustrative tendencies in art-making, whilst Randy Klein builds on a notion of the narrative and sequential elements in his sculpture and installation. For both of these very different artists, the uniting factor is the notion of a dramaturgy that challenges the 'text', offering contradictions to the viewer's expectations.

But back to theatre. Having acknowledged the process of dramaturgy in the creation of a theatre piece, does it then follow that we need to appoint someone as dramaturg for the production, or is this an unnecessary luxury? And what exactly does a dramaturg do? In answer to the first question, director Maggie Kinloch made it clear that many theatre practitioners act as their own 'native dramaturg' and that in collaborative theatre-making there is often a group dramaturgy employed. Yet to work with someone who has a definite role as dramaturg frees the director to focus attention on their main task, which Kinloch sees as guiding the actors to achieve their best possible performance. In British theatre we do not have a tradition of employing a dramaturg, but often someone has fulfilled this role under another name – be it producer, literary agent or assistant director. As pointed out by Lloyd Trott of Goldsmith's College and RADA, critic Kenneth Tynan was to all intents and purposes a dramaturg to Laurence Olivier, during his tenure as artistic director at the Royal National Theatre.

This brings us to consider what a dramaturg does. Are dramaturgs artists in their own right or facilitators of other people's art? Are they an external observer or a collaborator in the process? An agent of the text or someone who confronts the text?

There are no definitive answers. But to get a clearer picture of the different aspects of the role in action, it can be helpful to look at the distinction between what is sometimes called a 'desk dramaturg' as opposed to a 'floor dramaturg'. The former is often more akin to the traditional view of a dramaturg as literary agent – someone who acts as an intermediary between writer and director or producer by choosing scripts, arranging translations or suggesting themes for a theatre season. The latter is someone who is involved in the rehearsal process, a collaborator who acts as a bridge between all the elements of the performance and all the artists involved in its creation. Janine Brogt of the Toneelgroep Amsterdam – who describes herself as someone who became a dramaturg as a positive career choice – talked of the different ways that the hands-on approach might work. In some Toneelgroep productions she is involved from the start, developing ideas, researching, sowing the seeds. In others, she is called in at a later stage, and her role is more of a 'carpenter' – chopping and moving elements of the work until it all fits together more snugly.

The notion of shaping a production was one that came up numerous times – particularly in relation to physical and devised theatre – where it was felt by many that tendencies towards vagueness and shapelessness should be challenged.

Although it is sometimes thought that the function of dramaturgy is to add more layers and ideas to a production, it is often the opposite that is needed – a dramaturg is just as likely to refine and pare down the work to its core or essence. Bettina Masuch, resident dramaturg at Berlin's famous Volksbuhne, talked of the need to act as a human seismograph who can feel and interpret the needs of the production. It could be said, perhaps, that the dramaturg has no allegiance to anyone or anything other than the work itself, and their duty is to see how that work is best served. In the case of devised theatre, this can mean being what Nick Wood of Central School of Speech & Drama describes as, 'the agent for the text as it emerges' – the person whose job it is to keep the best and chuck out the rest. Janine Brogt corroborates this idea with her assertion that her role is often to be 'a pain in the arse', or as Maggie Kinloch says, 'someone who asks the question "why?" and insists on getting the answer'.

Why then do directors subject themselves to this torture? Because ultimately it results in more challenging work. In another interpretation, the dramaturg was described by Alison Andrews as 'the eye of the audience'. This is not the ‘outside eye' that is referred to so often in contemporary performance – the notion of someone who is not involved in the artistic process giving an objective opinion. The eye of the dramaturg refutes the binary division between subjective and objective and offers an alternative: a translator of meanings who can offer a balance between theory and practice, the internal and the external, the semiotic and the symbolic. The dramaturg in the role of audience's representative is no passive spectator, but a reminder that in any performance the audience is an essential part of the equation, the final collaborator in the creation of the work.

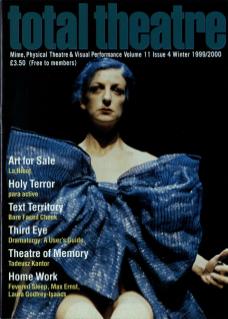

Dramaturgy: A User's Guide was organised by Central School of Speech & Drama in conjunction with Total Theatre, with John Keefe acting as Dramaturgical Consultant. A full report is available free to Total Theatre members.