I think I was expecting something more ostensibly Soviet, bearing in mind the memory of the 'Union' from which Latvia gained its independence in 1991. My friend slows her car as we cross the Daugava river on our journey from the airport – I lean out of the window and take a photograph of the old town ahead of us.

It is the turrets in particular that make me think of Germany rather than Russia, but perhaps it is the cinematic Germany of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Already, then, other places, other performances, merge to stage my encounter with Latvia's capital. Riga is beautiful, but – as my tour moves beyond the old town – it seems to be at least three different cities co-existing side-by-side.

Frequently as a spectator of site-specific performance I find myself also in the role of tourist, and these two experiences greatly inform one another. Over four days in Riga the city was performed for me in a variety of ways, both within and outside of the theatrical events I had gone to see. Framed literally at times through my camera lens or the car window and metaphorically through the stories and anecdotes of my Latvian friend; experienced at different tempos – the lingering pace of an empty bar on a Sunday evening, sipping coffee at the window; the steady amble of a shared walk through the rainy streets: the gliding stop-start of a tram; the bumpy urgency of the bus taking festival guests to the Daugavgriva Fortress – the city hints at its theatrical possibilities.

Last year Riga was more than usually conscious of the way in which it performs itself, both for its residents and in a wider European context: 2001 marked the city's 800th anniversary and 'Riga 800’ celebrations and commemorations filled the streets. Homo Novus 2001 was organised to fit alongside these celebrations.

The festival aimed to provoke a dialogue between performing arts projects and city surroundings and to 'decentralise art from the city centre to the neighbourhood'. Between the 14th and 23rd of September 2001, performances were staged in, among other places, petrol stations, a ruined fortress museums, private houses, and an ex-Soviet airport. Political motivations are evident here, reflecting an impulse to use a variety of spaces as a means of reasserting a collective and civic identity following a problematic political and social history. In many ways, Homo Novus 2001 was as much an advertisement for the city of Riga as any tourist brochure.

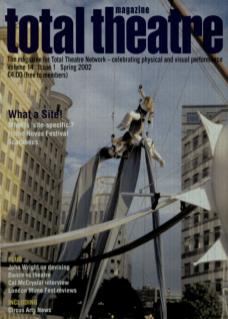

So what are the landmarks, the places of interest, on my tour of Riga as staged by Homo Novus?

First on the itinerary is the Daugavgriva Fortress. Formerly a military site, it is now little more than a crumbling wall offering a number of different performance levels. Here, a mystery play – I Played, I Danced – is presented by the Lithuanian group Miraklis. The performance is visually and aurally stunning, with its use of colourful puppets and masks, fireworks, dance, and a haunting new musical score. Baltic myth and music are commodified for me in an evocative setting. I begin to feel slightly uncomfortable in this touristic experience – taking pleasure in a beautifully packaged product whose words and cultural significance I can't understand. Always attracted to non-theatre spaces, the group asserts that ‘each performance fits organically into the surrounding environment, its relief and atmosphere'. But is an ‘organic' fit the most interesting way of engaging with a site?

The following evening a group of us squeeze into a car and drive to a petrol station on the outskirts of the city. A Norwegian group – The Passage Nord Project – performs The Night of the Inkpot on a stage built between the rows of pumps. This stark, unwelcoming space is overlaid with other spaces by means of a video screen on which images of Morocco are projected; a theme of alienation emerges as the live performers (three Norwegian and one Algerian) interact with their virtual screen presences. But the site plays little more than a superficial role in all of this, as director Kjetil Skoien is regretfully aware. He tells me that the performance will move to another petrol station the next day; Statoil, the company that owns these sites, is the chief sponsor of Homo Novus 2001.

On the Sunday before I leave Riga I see two performances presented by major Latvian theatres. Both are based on pre-existing scripts, but have enjoyed the luxury of extended rehearsal time within their sites. Thirsty Birds inhabits the fascinating ex-Soviet airport at Spilve and makes aesthetic and conceptual use of its waiting room location. But what remains with me now is the memory of the space itself: its faded mock-Roman architecture; its atmosphere of musty disuse. Sometimes, it seems, a site can resonate powerfully for the spectators almost despite the performance. Later, sitting with other spectators in one of Riga's communal apartments – another relic of the Soviet era – I contemplate whether I am still occupying the role of tourist, or whether something else has taken over. This is the apartment of the lead actor in The City (the second of the Latvian productions), and it is here that I begin to experience the intimate potential in this meeting between performance and site.

These performance experiences, intertwined with my touristic encounter with Riga, start me thinking about cultural differences in attitudes to place and space; about corporate ownership of site; about tourist photographs as site-specific documentation; but most of all about issues of site-specificity (or, more generally, the use of non-theatre sites) in festival conditions. Within Homo Novus the performances most able to interrogate their sites were the home-grown ones; in the visiting performances the site became a backdrop – interesting in its own right but not made more interesting by the theatrical encounter. None of the performances took the site as a starting-point for devising, and therefore the festival as a whole was not able to get the most out of its purported 'site-specific' stance.

The notion of a 'site-specific festival’ carries a number of immediate problems. For a start, practical considerations mean that festivals are commonly restricted to a particular area, thereby restricting the types of sites that can be used and range of performances that might be created. Some artists enjoy rural spaces; others need to engage with the urban. The chances of these two groups meeting at a festival are slim. The 'international festival’ compounds the problems – the pragmatics of time, money and proximity mean that visiting work is unlikely to have been born out of creative engagement with the place of presentation. This is where site-specificity breaks down and becomes something else instead...

I don't want to suggest that the site-specific festival is an impossibility. Rather, I'm excited by the idea and the new possibilities it seems to offer for intriguing juxtapositions and dialogues between work. But we need to be aware of the whole set of problems that is created when a festival aims at site-specificity.

So what might an ideal site-specific festival look like? Perhaps here we could draw on successful existing models such as LIFT (the London International Festival of Theatre). This formerly biennial festival has been represented in the national press as Britain's major pioneer of site-specific performance and has afforded artists the opportunity to engage fully with their sites. Now almost legendary examples are Deborah Warner's two performance installations: the 1995 St Pancras Project that explored the disused spaces of the Midland Grand Hotel, and The Tower Project of 1999, in which spectators were led one at a time through the upper floors of the former British Telecom tower at Euston. But even in the example of LIFT, site-specific work is balanced with other modes of performance. Imagine instead a wholly site-specific festival in which both local and visiting practitioners are invited to create different performance-based approaches to a set of interrelated sites. Both familiar and touristic responses to the environment might be brought together, generating a real debate about how we create meaning from the spaces we inhabit and visit.

Further details of Homo Novus 2001 can be found at http://vip.latnet.lvjti/homo/eng For more details of the ongoing LIFT festival see www.liftfest.org