‘For me, looking at the theatre world at the moment, there's a great lack of vision,' says David Glass. ‘We are talking about visionaries, artists who are trying to find a language which they don't see around them... their thinking is quite evolved beyond what is happening at the centre, and there won't be many forms that will easily sit with that vision.' Glass sees vision as born from the psyche of an individual artist, rather than inspired by the work of other artists. ‘Companies going into theatre have usually seen a show they've liked, they've been inspired by it. It's not often that it has come from a personal vision of theatre, something they're not seeing.’

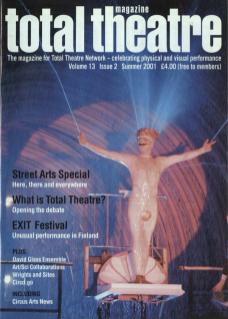

Given their discomfort with established forms of expression, and their notorious 'difficultness' as people, how do visionaries fit into the most relationship-based and collaborative of artforms, theatre? Glass is talking of people such as Pina Bausch and Lindsay Kemp, but he is himself a good candidate for the title. His show Unheimlich Spine – The Unhomely Spine (shown as a developmental piece at Riverside Studios, London, March 2001) certainly grows from a unique and personal vision. I witnessed its realisation during an intense three-week rehearsal period, the culmination of half a year's research and development.

Unheimlich Spine is the first piece in a new cycle of work exploring our relationship to our body. Its focus is the backbone, conceiving it as a repository of fear and anger. What better form through which to explore these emotions than through the genre of horror? The play's major source is the horror film The Tingler in which a scientist discovers that extreme fear causes a creature to grow in the human spine, crushing it and ‘killing a man, to death' (as Vincent Price's wild-haired descendent, Doctor Belle-Merde, says in Unheimlich Spine). In the original cinema release of this 1959 cult classic, director William Castle wired up the seats with electric buzzers to give the audience added shock value. The Time Out Film Guide describes it as 'clearly the work of a sick mind'. This film has enormous personal resonance and childhood associations for Glass, and formed the basis of the play's starting point, the ‘dream scenario': 'If you watched The Tingler then had a dream about it, this might be the story of the dream.’

The process of communicating Glass' vision began when Athena Mandis, the dramaturg, and Ruth Finn, the designer, came on board. They describe a process of helping David Glass to identify the vision. ‘Really he still just had the sense of it in his head and he could go to colours,’ says Ruth Finn about this early stage. Once they had a scent of the piece, both collaborators undertook their own research: Finn did visual explorations, Mandis read about the spine and related themes (it is she that drew Glass' attention to Freud's essay on the uncanny that gives the play its title) and researched 1950s films. Their findings facilitated Glass to formulate the dream scenario. ‘Our creativity came from teasing the vision out of David. It was almost as though David was the text,’ says Mandis.

In the next phase of realisation, Finn and Mandis both had their areas of responsibility: Finn to create the design elements, Mandis to create the play's speeches from dialogue borrowed from 1950s films. As Finn explains, Glass retained an initiating role: ‘I very much feel that the programme shouldn't say "designer: Ruth Finn". I think it should say "design realisation"... I feel I co-designed it with David in that I was taking things from him and interpreting them. Maybe "design interpretation" is a better way to say it.’ Glass' account tallies with this: ‘She knows I have a very strong visual sense... She's always very generous, allowing me to have quite a strong hand in that.’

Despite the piece coming from Glass, both participants claim a strong feeling of personal investment. They bear tribute to his skills as an inspirational leader: ‘David has the amazing ability to make you feel 110% creative, he opens you up. I feel more creative than with a director who's solely handing every decision over to me. So you feel you're being creative, yet, within all of that, he knows exactly what he wants and he's guiding you there.’

While the two core participants saw their roles as specialists facilitating the realisation of Glass' vision, the actors were expected to come to rehearsal with a vision of their own. 'You must each have a vision of what it might be,' said Glass on the first day of rehearsal. ‘If you don't, it is your responsibility to find that.' To help them find a vision, the actors undertook individual research. Prior to rehearsal, they read, watched a lot of films, kept a 'fear diary’ and engaged in character-related tasks (for example, Therese Bradley would sing to herself in a mirror every evening).

“I wasn't interested in what was coming out of the conscious mind of the actor... I was interested in the unconscious mind”

For the first two weeks of rehearsal, mornings were devoted to visualisations and physical and emotional explorations of the spine and the body's interior. It is here that a conflict arises: once the actors have a vision of their own, they expect to articulate and realise it. But the rehearsal allowed few opportunities for them to even discuss their vision. Forum discussions were drawn up but did not really allow full and detailed discussion. Nor did the improvisation work give scope for actors to explore their own ideas or alternative narratives: they were strictly based on the plot-points in Glass' scenarios. One of the actors explains their frustration with this: ‘I found that a lot of things were imposed... and I felt occasionally there were areas that we didn't go into because he guided very, very strongly. And one did feel slightly manipulated occasionally... and not knowing necessarily why you were getting into that area.'

In Glass' view, verbal articulation and discussion are not the way to contribute to a piece. Actors' contribution comes in the form of the qualities they bring to an improvisation, not from what they say. The individual research and morning work attunes them to the world of the play, colouring the qualities. ‘You have to discover it and you have to feel it and it has to be in your body,' says Amit Lahav.

‘I'm really interested in the bio-neurological presence of people in a creative situation,’ says Glass. ‘I wasn't interested in what was coming out of the conscious mind of the actor as deviser, I was interested in the unconscious mind... It's kind of difficult because they don't know they're actually producing things, even though it's come from them.' If Glass sees actors as voiceless and unconscious generators of possibilities, why then ask them to come with their own vision? Because, he says, vision is the basis of a creative relationship. Not having one is ‘a kind of stubbornness’. ‘When I'm pushing you like this – he pushes the palm of his hand against mine – we have contact because you have your vision. We can make a relationship.’

Glass requires of his participants an active openness that is not passivity or emptiness. Openness demands both a certain objectivity (avoiding ‘territorialism', the need for ownership or to impose one's vision) and responsibility over one's place in the process. It also means trusting oneself to creatively respond holistically, that is, from the emotional, bio-neurological, psychic levels, not only through what is conscious and verbalised. This openness is something that Glass expects from himself, and from the audience. If we come to his work with openness, we might be rewarded with a holistic experience that resonates with our unconscious levels, without our needing necessarily to know what it 'means' literally or where is it going.

As Unheimlich Spine demonstrates, this does not mean a humourless and obscure evening. There is certainly a vision in this play, and the form it is currently finding is one where stylistic weirdness, spoof and grand guignol combine to shake us up through laughter, shock and tears. When it tours again in the autumn, it may serve to prove that we as an audience can open to highly individual work, and that there is still a place for visionaries in our theatrical climate.

Unheimlich Spine will tour the UK from November 2001.