I am a performance and theatre artist, a poet and writer, and an entertainer. Sometimes when I am working at my highest ability I am all those things at once…

I was an imaginative child. My very first obsessions were based on fairytales, and I lived in the metaphysical realm, with imaginary friends that were either fairies or angels. This also included intimate relationships with inanimate objects like rock formations, fields, swamps and groves of trees, based on fairytales and magical stories from my pagan southern Italian culture. Later, I was obsessed with Hollywood and fashion. I compulsively read movie magazines and hairstyle magazines and tabloids which I discovered when I was allowed to go to church on my own, using the 25 cents my mother gave me to put in the collection box to purchase the tabloids.

I dreamt that I had been discovered as a child movie star (like my mother’s favourite actress Shirley Temple) and that I was going to bring my family out of poverty by being a movie star. The crisis each night was that I believed I had to also write the movie, which kept me in a perpetual state of anxiety because I believed that this was how I’d save my mother, a single-parent sweatshop seamstress with four children.

By the age of nine I was completely submerged in a fantasy world – I was actually convinced that I was in the television series Bonanza and Zorro and that roles had been written especially for me on those shows. I was brought screeching into the real world when another nine year-old girl told me she no longer wanted to be friends with me. I looked at her and said, ‘That’s OK but you can’t be on Bonanza anymore!’ She looked at me with the strangest expression and said ‘Bonanza is not real!’ and I burst into tears and shouted ‘Bonanza IS REAL! It is REAL!’

‘I was 13 when I started, ran away and I departed, from that town where I was martyred.’ By the time I was eleven, the entire town was wrongly convinced that I was having sex with everyone. It was a very painful time in my life as I had no one to appeal to, no one to take my side or protect me, least of all my own family. I was an outsider among outsiders, which moved me increasingly further and further away and out of any society. I was a loner compelled to follow my destiny.

I was told I was bad by nature, that I had ‘bad blood’. But I don’t think of myself as a bad girl or as a rebellious person. I think of myself as a good person in a bad society. Am I still a ‘bad girl’? Do I still get cut out and left out of parts of society that are based on maintaining the status quo by pursuing at all costs my personal truth? As a woman in our culture that hates women – that especially hates smart and strong women – and as someone who could not hide my difference, my queerness, I was belligerent when faced with the petty lies and hypocrisy of the bourgeois world.

I became an artist because I was compelled to express myself. This was my earliest sense of myself, my desire to create my own reality and to escape oppressive emotional circumstances which I had no control over, and couldn’t deal with in a conscious way. Creating theatre deals with these subconscious feelings in a conscious way, making use of them in a transformative way.

Being an artist was not a career choice in any sense: even when I was a Warhol superstar at nineteen and was told I had a career, it made little impact on me. It was much, much deeper than that, and it has only gotten deeper as I have grown older. I now, many years later, see it as my role in life. Everything in my life was and is funnelled through my imagination and creativity. It is the only way I have ever known how to make sense of life.

I met Andy Warhol through ‘Superstar’ Jackie Curtis. Andy was a friend of John Vaccaro’s and a fan of his theatre, The Playhouse of The Ridiculous, where I was performing. Andy came to see all our shows. Andy asked Jackie to bring me to the Factory because he had seen me on stage and was looking for new ‘stars’. I was the ‘It’ Girl of the downtown art scene in 1969 because of my performance style and my youth and my ability to communicate verbally with anyone. By 1969 Edie Sedgwick was quite diminished by drugs and mental illness. Viva had moved on to other things. They were all a lot older than me. I was precocious. I had met Taylor Mead on my own, on the streets of the East Village which is the way one met most people in those days. I wanted to be like Taylor. He was a comedic genius.

Andy Warhol didn’t pursue content. It was we who brought content to him, and that was why he needed us. None of us were interested in ‘real life’ but Andy was the least interested. Andy was like a metal detector. He detected ideas. He didn’t actually work from his own ideas. He found ideas in other people. That was the genius of his mind. His ability to find, follow and act on other peoples ideas. It is this quality of his mind that makes me say that Andy convinced the art world he was an artist when he actually was an art director. You see his influence and a great deal of his legacy in advertising, because there is so much art in advertising today, and so little art in art.

Glitter, that is what is left from those days. And the magic that resides in some people’s spirits that nothing – no hardship, no criticism – can remove, then or now. A twenty-something drag performer was at my house the other night changing for a performance in a nearby club. She said, ‘I have to warn you, I leave glitter everywhere.’ I replied, ‘Don’t worry about it. I can take you to East Village apartments where people are still annoyed by the glitter I left between their floorboards in 1968.’

I will say that very little has actually changed in ‘sexual politics’ over the years. It has just shifted, and in some ways the situation is worse because the issues have been deflected. Transgendered people are still on the lowest rung of both the gay world and the straight world. Bisexuals are still considered aberrant and lesbians are still invisible and do not have the cachet that gay men have long enjoyed.

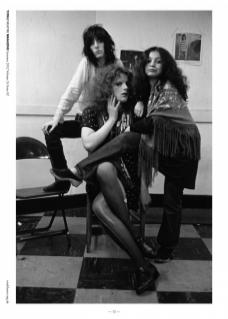

My sex and censorship show Bitch!Dyke!Faghag!Whore! still has a massive impact today, even though it was written twenty years ago. People routinely come up to me after the show and say: ‘No one is saying what you say in this show! It is so contemporary. I can’t believe you didn’t write it this year.’ The show started as a solo fellowship audit for the National Endowment for The Arts in 1990 at the height of the Censorship Crisis, what is now called The Culture War – a war that incidentally has never ended in the USA. It was meant to run for four performances. It sold out immediately and continued to run for two months. It began as an improvised show, like all my work, with just ideas that I take on stage with me and two women strippers, Arlana Blue and Diana Moonmade – both staunch freedom-of-speech advocates and feminists. In 1990, in NY’s downtown art scene, which was highly politically correct, strippers were simply unacceptable. You could play a stripper in a play but you couldn’t actually be one without being seen as pandering to the patriarchy. In 1992, Mark Russell, of Performance Space 122, which had lost its funding (like every other theatre that presented queer work during that period) and was looking at having to close the venue, unable to pay salaries, asked me to bring B!D!F!W! for the summer. It ran and ran…

I decided that I needed to include men in the show if I was serious about my feminism, because feminism that doesn’t include men and strippers is not a feminism I can be part of.

It was a queer show, based on political humanism that said: We are all equal. We are free, and so don’t use your gay liberation to oppress my gay liberation or my inclusion in the human race. The show represented ideas and values that did not have a voice in the theatre or anywhere else. The queer politics that I espoused in the show were in complete contradiction to the ‘gay’ world that either sought to distance itself from anything that seemed unseemly, or had completely capitulated to a very narrow ghetto marketing mentality – to the point where it was creating the same institutions of distrust, hatred and oppression towards heterosexuals, bi and transgendered people that decades of gay people had suffered from.

Of course Quentin Crisp was a big advocate of the show because he had been the victim of so much oppression by the ‘politically correct’ gay world. It was, and remains, a very important show about personal freedom and individuality. We played at the legendary Village Gate (which had launched Lenny Bruce). Many, many people saw that show at least three times and as much as 25 times, bringing everyone who mattered to them. It is a show as much about the audience as it is about me, my ideas, and the dancers.

The question the show has always asked is: How do we live now? How do we really live? How do we find the freedom to inherit our natural legacy of joy and fulfilment? How to love ourselves and stop feeling oppressed and tortured by other people? How do we stop hurting others, stop limiting others because we ourselves feel hurt and limited?

The truth is that someone will always be ‘queer’ because humans are pack animals, herd animals, and humans want other humans to fit in with the crowd. Humans don’t like outsiders, but then conversely humans admire outsiders when they are at a great distance, not in their midst – and they especially admire outsiders once they are dead. Look at what dying did for Jesus Christ, Van Gogh, Frida Kahlo!

The kind of censorship that two decades ago was rampant in America, and is still rampant today, has infected the whole world.

B!D!F!W! is grounded in separation of church and state. When I performed in Britain twenty years ago, the British press was shocked by how narrow-minded America was. They were stunned by the fact that no American newspaper, or radio or television show, dared use the title, except for the Village Voice. From The Times to the Guardian to local British newspapers, the title twenty years ago was not an issue in the UK. This year I was a guest on the Joanne Good show on BBC1 and before I went on the air the producer took me aside and said: ‘I am afraid we can’t say the title of your show on the air. BBC rules.’ Jo Goodman and I spent the rest of the show speaking about the censorship that has crept into Britain. Twenty years ago there was no Born Again Christian movement in Britain. Now it is everywhere.

I see very little real politics in performance art today. Politics meaning what we do to one another in the world, culture meaning how we talk about what we do to one another in the world. Most of the work I see among young people is about personality, their own. The values of any given era are reflected in the work of that era. There is a big focus on becoming famous, and successful. The work is very career driven, which limits how political people can be or want to be. The artists I know who are political are marginalised. It seems there is a haze of political meaning to work, like a veil cast over the concept of it, but most of it is about themselves – not all of it but a great deal of it. This is natural I suppose when people come directly out of school into ‘Performance’: there is very little life experience to draw from, so much pressure to be successful and to have a career, with art being taught as a profession – when art is in fact a lifelong vocation.

There is nothing in the world that compares to seeing the work of artists who have consistently made work for over 25 years. Art is one of the things that one gets better at doing. I have long loved the work of Richard Foreman, The Wooster Group, Lee Breuer of Mabou Mines, Bill Forsythe, Meredith Monk, John Jesurun, performance poet John Giorno, Peggy Shaw and Lois Weaver… Amongst younger artists, I admire David Hoyle, Robert Pacitti, Taylor Mac, Meow Meow (amongst many others), and I am often as influenced by painters, photographers and musicians (from Leonard Cohen to Patti Smith and beyond) as I am by theatre-makers – perhaps because I am fundamentally a conceptualist.

I do not think and then speak. I think as I speak; I find out what I am talking about as I speak. Every good line, every powerful line in my writing, was born by my speaking it to someone in real life, long before it was spoken on stage. Or it was born on stage while I was supposed to be saying something else. To improvise is to be a medium, to be an antenna. It is a somewhat frightening thing to do because you have to relinquish control on certain levels.

I am very happy. I grew up to be the kind of person I wanted to be. I am very proud of my work… Everything is next!

Penny Arcade is a writer, poet and theatre-maker/performance artist. Always a keen documenter and observer of people, she wrote her first play when she was fourteen years old in reform school (Borstal).

She started performing professionally aged eighteen, creating improvised theatre with The Playhouse of The Ridiculous, and then joined Warhol’s Factory aged nineteen. She continued to work with various different experimental theatre groups (as a performer, poet and singer) until she was 34 years old, when she launched her own work as a performance artist. Although she moved on to create scripted work, she has always maintained a high percentage of improvisation in her live shows.

Penny Arcade’s seminal work Bitch!Dyke!Faghag!Whore! premiered in 1992, and ran to great acclaim at PS122 and the Village Gate in New York City, subsequently touring to twenty cities around the world between 1993 and 1995, with an itinerary that included two tours of Australia and a successful run at the Edinburgh Fringe. She retired the show in 1995 and created four other full-length shows. The show was revived in 2006 and has enjoyed great success since. It will be performed 27 June - 22 July 2012 at the Arcola Theatre, London. www.pennyarcade.tv

Penny Arcade also creates ‘hosting monologues’ for Pussy Faggot, a performance art party she has hosted over the past three years for Earl Dax. www.pussyfaggot.net

Apart from her performance appearances, theatre-making, acting and touring, Penny Arcade currently also writes poetry, essays, and magazine articles. Her long- running video documentary series – The Lower East Side Biography Project, Stemming The Tide Of Cultural Amnesia – was created with long-time collaborator Steve Zehentner (Steve is also dramaturg on Bitch!Dyke!Faghag!Whore! and the designer of Penny Arcade’s work). It broadcasts weekly on cable television on Wednesdays at 11pm NY time, and is also available online at the same time. See www.mnn.org