It is true – teachers can change your life. As a suburban girl attending an ordinary Australian high school, our tenth-grade English teacher was a gift. He had us reading widely. I stumbled across Ibsen in the library and I worked my way through all his plays. Our English teacher also set us regular creative writing tasks. He gave me a leaflet for some creative workshops that were happening outside of school but instead of the writing workshop, a course on drama caught my eye. It was like a lightbulb going on.

My first year at university coincided with the advent of a new drama course with a practical component – and the smaller French Literature module I took explored the Absurd playwrights. After graduation I got a job as a copywriter in advertising, but in the evenings worked at a repertory theatre called La Boite. The theatre building was designed by an architect specifically to support productions played in the round (the space could also be adapted to a thrust stage). The programme of work and the design approaches were fresh and innovative. Working in the round brought a training in audience awareness and the use and potential of stage space, and I was fortunate enough to play roles like Shakespeare’s Juliet, Kate Hardcastle from She Stoops to Conquer, and Shen Teh / Shui Ta from The Good Person of Szechwan.

At La Boite, I was also cast in an experimental production of Beckett’s Act Without Words. At this point I had some dance training but no mime training at all – we invented as we went along. The director would say things like: ‘When the scissors come down can you react with your body? Make a big gesture before you touch them.’ The theatre had no flies, so we had a talented young visual art student sitting on top of a ladder, clearly visible, with a fishing rod – she hooked each item up and dropped it in on the line. It was a budget-free production and for costume I ended up wearing black tights and a genuine marinière (striped sailor’s top) borrowed from my French then boyfriend – by accident or default, copying a classic mime look. The same young director, Sue Parker, also cast me in a surreal cartoon-style piece based loosely on Of Mice and Men.

Important moments that grew my appetite and imagination were watching university productions featuring the actor Geoffrey Rush and others who had returned from studying at Lecoq school. Trevor Stuart (then Smith) was in a superb production of Peter Handke’s abstract, clownesque (and in the second half, audience-alienating) play Kaspar. I found both performance and play compelling.

I was never drawn to apply for Drama School (did I associate it with naturalism?); advertising was my day job and nicely supported the work at the semi-professional La Boite, but the next step was unclear. A chance set of circumstances led my boyfriend and I to decide to head to Europe. We let go of our rented flat, sold our cars, and struck out with the idea of either finding theatre work or attending workshops. We planned to stay just one year. My boyfriend got a job in TIE in Birmingham while I stayed in London – and it was there, on Kings Road, that I ran into an actor from my hometown. She’d been working with Hull Truck Theatre Company, and for some reason the first thing she said to me was, ‘You’re interested in mime, aren’t you?’, and started telling me about Desmond Jones’ School of Mime. It took me years to realise she must have seen a picture of me, in my stripey top, from Act Without Words. It was a coincidence that would have a far-reaching effect.

Three Women Mime

At first I attended weekend workshops and evening classes, and then Desmond Jones opened the Desmond Jones School of Mime, in 1979, at the British Theatre Institute on Fitzroy Square. There was something about the technicality, the discipline, and the humility of mime practice that drew me in. Desmond would quote Decroux: a mime was ‘an actor with the body of an athlete and the heart of a poet’. I would walk to school each morning along the Marylebone Road, doing Decrouxian hand exercises: palette, trident, coquille, salamander, marguerite; repeat.

During those early evening classes I met the artist Tessa Schneideman. Tessa was a painter who’d exhibited at the Royal Academy and the ICA with strong and slightly surreal figurative pieces done on large canvases. I was fascinated that, although she was an exceptional artist, she had changed direction and come to mime because painting was ‘too solitary’. We teamed up with a third artist, Claudia Prietzel, who had trained as a puppeteer, and formed our own company, Three Women Mime.

Our first public performance was at the York & Albany – a pub theatre at the top of Parkway in Camden. Back in those days people associated mime with the ‘Everyman’, and many people were using the classic illusions of opening windows and flying kites. I thought: ‘I believe that we are the first all-female mime company; let’s say so, and see if anyone tells us we are incorrect. Let’s see what subjects we can address, let’s see what we can do that is different and relevant.’

The first piece we made together at school was three women standing side by side, looking into a mirror, dressing and putting on make-up. Each gesture further constrained their faces and bodies. For another piece, a cloth was hung so that only our legs were visible and our legs and shoe collection worked as a kind of puppetry, with diverse characters interacting, including a mother dragging a line of tiny shoes like a ball and chain. Tessa built a giant cream bun for one piece (in defiance of the fairly robust notion in those early days that mime should be a pure form consisting of a figure on a bare stage). In one piece three women in aprons and headscarves performed an entire circus using household objects. Over the course of three shows we addressed subjects including food issues, motherhood, the depiction of women in popular culture, and sexual violence.

Hilary Westlake of the seminal Lumiere and Son Company agreed to direct a piece for us: Wounds. Hilary proposed that ‘the only thing that separates women from men is that they bleed’. At the time, Hilary was working with these stamping dances and rhythms and gestures, and so we dressed in pure white costumes and moved in abstract rhythmic patterns, and at various moments blood would come from somewhere. The first blood came from a mouth, then a breast, from between the legs, and finally Claudia put up an umbrella and blood rained down on her. It was bold, perhaps disturbing but uplifting.

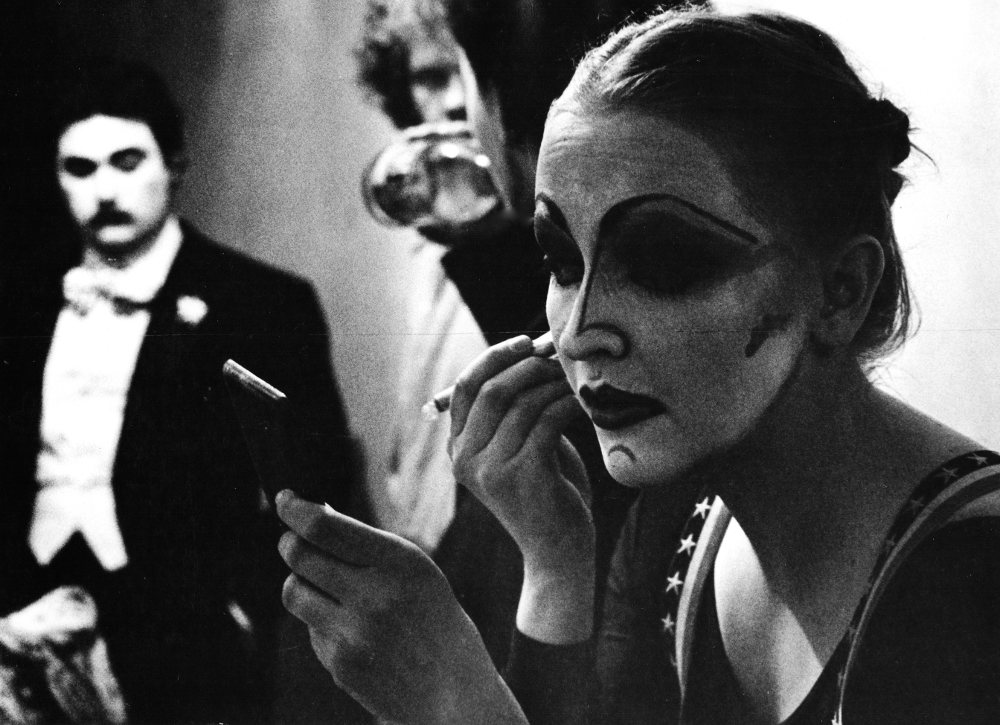

Three Women Mime at Barcelona Festival. (Photo: Patrick Boillaud.)

In the early 80s there was a strong scene of people practising mime – artists like Lorna Marshall, companies such as Intriplicate (Mollie Guilfoyle, Robert Williams, and Ian Cameron), Black Mime, Black Women Mime, Mime Theatre Project (Andrew Dawson and Gavin Robertson), and the popular and inspiring Moving Picture Mime Show (Toby Sedgwick, David Gaines and Paul Filipiak). Theatre de Complicité arrived on the scene a little later.

Fringe theatre had a much stronger touring circuit in those days and the Edinburgh Festival Fringe was more affordable to attend. Three Women performed at what is now The Pleasance back when it was called the Wildcat venue and had far fewer performing spaces. The Drill Hall was a hub for Fringe work. Time Out had a column devoted to Lunchtime theatre and I remember going into the basement of the Drill Hall to see a Sam Shepard play that was lit by a lightbulb in a jam tin – wonderfully grungy. Julie Parker was the artistic director and the venue supported and promoted gay practitioners. I remember seeing Rose English performing Plato’s Chair. It was in the bar – where they’d put in a small raised stage at one end. As we were sitting in the audience she literally ran round us, encircling us with this beautiful, silent loping. I loved the way she talked to us directly, talked to the technician, commented on the progression of the piece, her intentions for it and her journey through it. I wasn’t in the practice of doing this but I went home and wrote about the show, trying to define its effect on me: ‘she does so much with so little’.

Another important influence at the time was working with Lecoq at the British Summer School of Mime Theatre in 1981, and studying with mime corporeal company Théâtre du Mouvement, and with Sankai Juku. And in 1983 or 1984 studying for the first time with Philippe Gaulier – alongside John Wright, Phelim McDermott, Rick Kemp, and Annie Griffin.

Three Women were fortunate to receive consistent Arts Council funding and we toured around the UK and abroad with the shows High Heels, Follies Berserk, and Clotted Cream. We appeared in the London International Mime Festival and won an Edinburgh Fringe First. In the early 80s Edinburgh Fringe Club was somewhere artists performed extracts from their shows as a sort of promo – one year the Assembly Rooms had a cafe style venue where you could watch other companies, get something to drink and eat – a place where artists could easily interact. I met companies like Impact Theatre, and the wonderful and eccentric Cliffhanger Theatre. One year I watched performer David Glass doing quite classical mime – the following year I saw a show where he was mixing dance, mime and text and that interested me greatly.

It was seeing the blurring of the lines between disciplines and developing an appetite for new approaches that pushed me to take a step in a different direction. Three Women shows had been collections of short pieces, and after three years with the company I found I wanted to bring more dramaturgy, more of a sustained arc to the work. In 1983 I took the plunge and went solo.

Going solo

For my first piece I did as many theatre makers do and created an autobiographical performance. It was called Red Heart and it was about my experience of Australia – this country with its vast landscape, where most of the population clings to the coastline; and the strange contrast between banal daily suburban reality and the wide wildness and ancientness at the continent’s centre.

At first I billed my work as ‘mime theatre’. Somewhere along the way the term ‘physical theatre’ was coined. There are so many solo performers now but back then it seemed to be quite rare. There was a feeling that people would go to a solo show with a kind trepidation – possibly more so if the performer was a woman.

But through the 80s and into the 90s, I made and toured a lot of solo shows, often working with Rex Doyle as a director. Rex was an actor, director, writer and teacher who’d directed Alan Rickman in a play he had written and who had been a member of Mike Alfreds’ company Shared Experience. Alfreds was famous for taking a rich-in-process Stanislavskian approach to making work, and for adapting novels which he’d put on with barely any set. Before the RSC did Nicholas Nickleby, Shared Experience did Bleak House.

Rex created pieces with me that were sometimes movement-rich and sometimes, as in the case of Hiroshima Mon Amour (no relation to the film), a scripted character directly addressing the audience. Rex was an amazing enabler. He could embrace an idea or an impulse and contribute creative prompts that would help a piece to really find a full expression.

In 1988 I made a piece called Wendy Darling. I’d been having dreams about flying and Rex suggested I look into Peter Pan. My first idea was to do something where Wendy grows up and goes to Tibet and learns to fly the yogic way, but when I re-read the book the thing that really got me was the unrequited love – so inescapable and so painful. At the end of Wendy Darling, this woman who’s thirty is standing looking out the window impossibly waiting for a boy to arrive.

Wendy Darling was largely wordless. From my early impulse to work solo with few or no props; in this piece, the props unfolded the action. A woman arrives in an abandoned nursery. She realises it’s late and she decides to prepare to spend the night. Things come out of a pine chest – a sheet and alarm clock, a book, but then leaves cascade from the pages of the book, and Neverland foams in: a conch shell, feathers, a boat and its pirate flag, a hook. Wendy’s fox fur comes alive, the crocodile bag eats the clock, a small doll flies out of the doll’s house…

Three Women had subversively revisited Cinderella – and in Wendy Darling I was again reinventing a familiar story from a new perspective.

Page, stage and screen

Apart from my solo work, I also worked with other artists. In 1992 I played the part of Fuschia in David Glass and John Constable’s adaptation of Gormenghast – a hugely successful and visionary show. David embraced both cinema and world theatre, and the staging of Gormenghast took ideas from Kabuki theatre to make something very filmic and powerful.

Instead of people entering and exiting laterally from the wings there was a black set at the back of the stage with doors of different sizes that could come in and out of their slots.

The performers had their characters to play but also worked as an ensemble of hooded Kabuki-inspired figures (design was by the amazing Rae Smith). One key scene had the loyal retainer Flay making his rounds of the castle with endless corridors, staircases and echoey slamming doors (amid a score and soundscape by John Eacott), all as if a Steadicam were following him and all created by the animation of the door-shaped screens.

A few years later I worked with David Glass again to make a stage performance for my own company (billed as Peta Lily & Co, because these were two-handers). Beg began life as a surreal relationship between a woman and a male figure unaccountably wearing a dog mask – inspired by Paula Rego’s paintings. Each of my pieces have been drawn from some issue or obsession in my own life – here the piece was fuelled by the difficult relationships I’d had with my father and my brother. In conversation with David Glass, the piece became re-envisaged as a Cronenberg-style schlock horror piece.

David and I had both been reading about serial killers – often some trauma they have experienced is manifested in ghastly acts which have a terrible creative logic. The character of Penelope (a medical surgeon) in Beg was a woman who felt so let down by men that, in order to make the perfect man, she would cut a man open, put a dog inside him, and sew him back up again.

The piece drew on and incorporated fairy tales – Red Riding Hood, Briar Rose, The Girl with the Silver Hands. Rae Smith transformed a hospital drip stand into a magical rose bush, hung with white and red bags of fluid. Independent film-maker Robert Golden initially disliked the show, but somehow he decided it would be a good project for a film – and with that it became rather a different beast.

The filming happened in Greenwich at the old Seaman’s Hospital, which back then was derelict and broken-down and freezing. In a corner you’d come across a member of cast or crew flipping through old abandoned hospital records. Beg! the film did very well at the Edinburgh Film Festival (in 1994, the same year as Shallow Grave), and also at Sundance and other places.

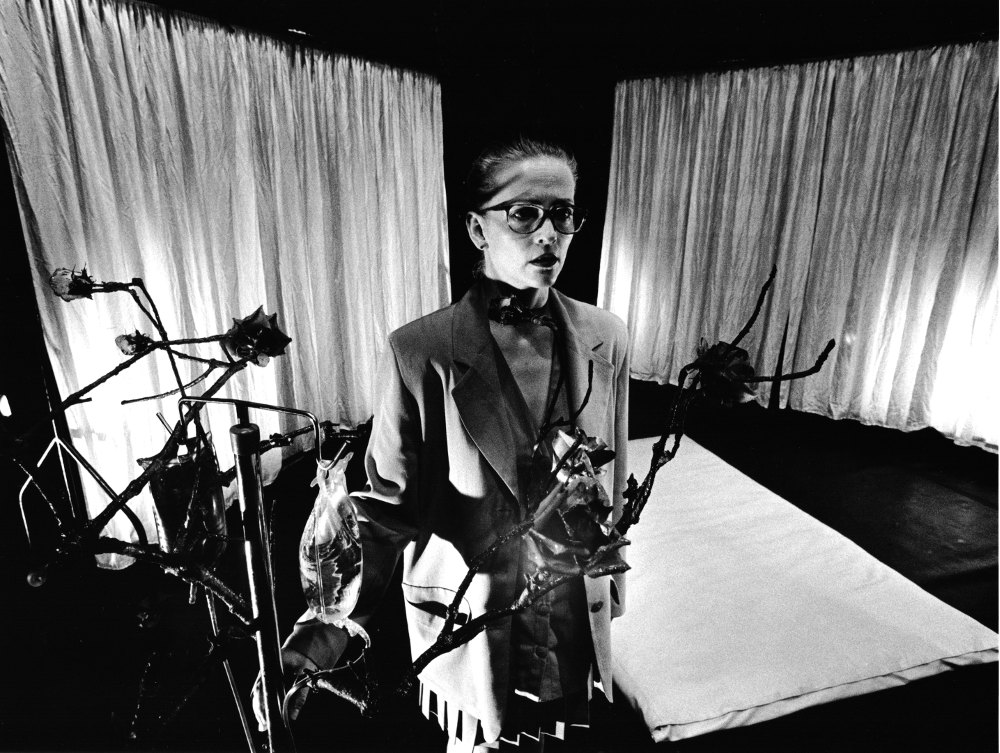

The stage version of Beg. (Photo: Douglas Robertson.)

Also that year I premiered a play called The Porter’s Daughter. I’d wanted to do a piece about ambition, about success. I was obsessed by this question of how do you become a success, and Rex suggested I look at Macbeth. I started writing and realised this was not going to be a solo show or a two-hander but a full-length, full-cast play.

I have always prized writers who lift the lid of things – speak of the secret and clumsy and hidden. The Porter’s Daughter became a below-stairs view of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. If King Duncan is coming to the castle, with all his men, that is a lot of cooking that needs to happen. I wrote about the cook, the porter, and the porter’s daughter (who is never named and referred to as Woman). A lot of physical theatre was sewn into it. The witches were a cross between Mother Courage and the Three Stooges and they don’t have any supernatural powers at all. Witch One is psychic but as for the apparitions and all the rest, they fake it.

The eponymous porter’s daughter is an abused character – I was curious to write a character like that who could endure, who would not be destroyed.

A trilogy & the Dark Clown

In ’95 my marriage broke down, my company lost its administrator, and I had to cope with illness – my own and my father’s – and the death of my mother. I was terrified by a whole new set of circumstances and not having the safety net of a relationship or a dual income. I thought, ‘Well, that’s it – I can’t create my own work anymore. I’ll work for other people.’

I had a wonderful process and tour working with and for Claire Dowie and Colin Watkeys on Claire’s two-hander play All Over Lovely. They invented ‘stand-up theatre’. Strong concepts, direct address, simple production values. In 1999, another accident – someone told me there were some nights free at The Lion and Unicorn and asked me if I wanted to show something. I had been meaning to write a show about the annus horribilis (actually anni horribiles: ’96 and ’97). I adopted Watkeys/Dowie’s form of ‘stand-up theatre’ and created the show Topless, which went on to tour the UK, Hong Kong, Athens and Australia.

The racy title often provoked people to quip, what next? And I would joke back – it’s going to be a trilogy. The next autobiographical piece, Midriff, was about the years following on from the events in Topless when I was questioning how to live, questioning whether I should go back to Australia to look after my father and feeling like a coward and a villain for not wanting to do that. I leaned on Hamlet (the lack of decision, the constant self-critique) for this piece. Midriff was a challenging piece to tour – it required a large strong table. Midriff played London, Liverpool and Hong Kong and for one reason and another, I did not perform again at all until six years later.

In 2008 I created InVocation (base chakra, existential crisis) which in a way is the final part of the trilogy. Although the 2010/13 Chastity Belt is an anatomical contender for part three but different in tone (there is a lot of rhythmic verse in it) and it is less directly autobiographical. On the theme of retelling stories from another viewpoint, Chastity Belt includes a playful rewrite of the character of Diana (Artemis) and of the play Lysistrata.

I have always aimed to make work that was exciting to the heart – that made you laugh but that troubled you or that touched you in some way (while steering well clear of sentiment). The starting points of all the pieces that I made, and a lot of what went into Three Women Mime, I guess, were these niggles – things that weren’t right, that were worrying me in my own life. So I’d investigate them, I’d take them as material and work them out in three dimensions. And I’d use whatever means I needed to do that.

At the same time as I was working on the solo trilogy I was giving more and more time to exploring and teaching Dark Clown. My Dark Clown work was born back in the ’80s when I saw the Pip Simmons Theatre Group at the ICA present An die Musik. One scene completely arrested me. A desperate character, someone stuck in a prison camp, was dancing and simultaneously hitting himself on the head, again and again with a metal tea tray. The audience laughed – but it was a particular quality of laughter – we were laughing but we felt we shouldn’t be laughing. It wasn’t the carefree laugh in response to the red nose clown, where you know they haven’t really hurt themselves. It was venting a kind of laughter that was quite visceral but that did not take away from the horror of what was happening – so you felt a release but also some shame, some sense of being implicated.

I was already regularly teaching clown and after that performance I started asking people at my courses, ‘Do you want to try an experiment?’ Luckily people would always say yes, and I started to explore what it was about that particular kind of laughter that had compelled me – I gave it the name of Dark Clown and at a certain point designed and began to offer the Clown & Dark Clown workshop.

In order to create Troubled Laughter, you need to know how to reliably create laughter. So in Clown & Dark Clown workshops we start clown and learn comedy craft which will then be applied over on the Dark Side. Many say that the clown holds up a mirror to humanity. Imagine a line representing human expression. Let’s say that on one end you have emotions which you can expect to see and feel with the red nose clown: silliness, loveliness, enthusiasm, bossiness, grumpiness, possibly even anger – imagine that line extending towards pain, shame, guilt, existential horror, desperation and terror. That is the realm of expression for the Dark Clown.

The most horrific events of history can leave us numb. There are appalling events which are almost unbelievable, hard to contemplate. The laughter that the Dark Clown work (done correctly) generates seems to me to vibrate at a level that matches the absurdity and obscenity of ghastly events better than drama can. And it is not a frozen shock; the work aims for shock to be shaken loose by the body, by the curious phenomena of the Troubled Laughter. The work aims to embrace our marginalised and suppressed reactions to horrific events. The work aims to allows us to witness (a portrayal of) moments where humanity has been forced to jettison its dignity and face ghastly choices. With the red nose clown you point and laugh in a carefree manner – the generosity of the red nose clown allows us to feel and enjoy our relief that this is not happening to us but to that idiot over there. The generosity of the performer presenting Dark Clown is to deliver as authentic a portrayal of suffering as possible while using the skills of comedy craft (contrast, rhythm, timbre, phrasing, repetition, musicality, etc.) so that the audience laughs, but feels the cost.

Peta Lily works as a performer, workshop leader, creative mentor and director. Alongside her own projects, Peta recently directed Sarah-Louise Young in her performance Je Regrette, and Lost in Translation Circus in Famished. Later in the year she’ll be working with John-Paul Zaccarini on his solo piece The Mixrace Mixtape.

For more on Peta’s current projects and upcoming workshops see her website: www.petalily.com