Watching Odin Teatret’s Thebes at the Time of Yellow Fever, Bianca Mastrominico reflects on the extraordinary six-decade journey of the company, the crossroads they have now reached, and the home of their legacy

‘It is the day after the last battle. The war between the two sons of Oedipus for the dominion of Thebes is over. The rebel Antigone has been punished for profaning the law of the city. Families bury their dead. Oedipus’s ghost wanders among the corpses. Creon and Tiresia are plotting for peace. The Sphinx and the plague lie in wait. For all of us it is spring, a time to fall in love. The future is a frenzy of sun and gold: a yellow fever’ (from the brochure of Thebes at the Time of Yellow Fever by Odin Teatret).

Mid November 2022. It’s a beautiful sunny day and I have just arrived in Paris, where walking briskly in darkness through the atmospheric Bois de Vincennes on the outskirts of the city, I am about to experience Thebes at the Time of Yellow Fever by celebrated ensemble Odin Teatret. After opening in Denmark and touring in Poland and Italy, the performance is presented at La Cartoucherie de Vincennes, the headquarters of Théâtre du Soleil, the Parisian avant-garde company founded by Ariane Mnouchkine, Odin Teatret’s longstanding comrades in the invented tradition of the European theatre laboratories, and historical hosts of the company in the French capital. The ensemble performance signals a turning point in the almost 60-year life of Odin Teatret, and of its founder and director Eugenio Barba. Its run marks changes in the company’s structure and base, away from the farm in the Danish town of Holstebro which Barba and his actors transformed into their theatre laboratory and artistic home in 1966, with the name of Odin Teatret – Nordisk Teater Laboratorium.

Thebes at the Time of Yellow Fever is performed by Kai Bredholt, Roberta Carreri, Donald Kitt, Iben Nagel Rasmussen and Julia Varley with the text and direction of Eugenio Barba (see end of this article for full credits).

It is based on the myth of Oedipus and the saga of a Greek family in the city of Thebes, which – as Barba writes in the performance brochure – ‘has accompanied my life in theatre since my very first steps’. From Oedipus tyrannus by Sophocles as a mise-en-scène project at the Warsaw theatre school in 1961, to El Romancero de Edipo in 1983 with Toni Cota, Barba brought the myth back in The Gospel According to Oxyrhincus in 1986. Here Antigone, played by Roberta Carreri, embodied what Barba calls ‘an archetype of thirst for justice and rejection of the laws of the city’. In 1990 he met the ’father killer’ again, while working on a new performance with Iben Nagel Rasmussen, and in 1998 Oedipus was one of the protagonists of the Odin Teatret ensemble performance Mythos, alongside the myths of Medea, Dedalus, Cassandra, Orpheus and Ulysses.

In an interview released to the journalist Anna Bandettini for the Italian newspaper La Repubblica, Barba observes that ‘Oedipus is an enigmatic story: a young person tries to achieve the saying from the oracle of Delfi, “know yourself”, and while pushed by the desire of searching for his parents, unwarily and unwittingly he triggers patricide, incest, plague and fratricidal wars’.

‘What does this myth want to tell me?’ asks the Italian born eighty-six-year-old director, who has turned his life as a migrant in Norway in the 1960s into one of the most luminous and prestigious theatre endeavours in contemporary theatre. Barba, who through personal revolt and an uncompromising work ethic has, with his performers, conquered ‘the difference’ of starting as an outsider of the Scandinavian theatre establishment, answers himself, as if interrogating his own existential quest: ‘Should we not know ourselves?’.

In Paris, the bohemian appeal of the bar-gazebo mounted outside La Cartoucherie’s theatre building that hosts Odin Teatret quickly fills with the casual chatting of a cosmopolitan mix of spectators of diverse ages, languages and backgrounds. I add myself to this vibrant and international theatre community, queueing at the entrance, and holding a ticket and a programme in the awareness that Thebes at the Time of Yellow Fever will be performed for the last time ever, on these premises, on 19th November 2022. A cycle in the life of an ensemble, which continues to inspire generations of theatre practitioners to push the boundaries of theatre-making through their ground-breaking experimental performance work, concludes in Paris to make room for new directions. Odin Teatret officially left the premises of the Nordisk Teater Laboratorium on the first of December 2022 and – as Varley, actor at Odin Teatret since 1976, announces on the Magdalena Project website – was ‘founded’ again as an association based in Holstebro, which will from now on provide the framework for its activities in Denmark and abroad.

‘I continue to move within the walls of Thebes,’ Barba writes in his introduction to the performance, ‘as if I predicted that one day, like Oedipus, I would be expelled from this city and would go ad venturas, towards things to come: adventures. The circle closes: the future, unexpected and unimaginable, brings me back to the uprooted conditions of my youth’.

Yellow, as I continue reading from Barba, ‘is reminiscent of gold, of the sun glistening on the fields of wheat and rapeseed, of the hair of some women I have loved, of Van Gogh’s hunger for life when he painted his sunflowers and sometimes, during his crises, swallowed this colour from the tube’. The above extracts from the brochure belong to six pages of diary-like entries on the making process of the performance, where Barba retraces its laborious genesis and reveals the maize of detours, sources and themes, which filter and mutate through the calculated serendipity of Odin Teatret’s ensemble craft. Only, it is more than just feeding the spectator with backstage stories or associative and historical meaning about the production. To me, a witness of many Odin performances, participant in training, and at various points in time a collaborator and facilitator of Odin Teatret’s work in the UK with my company Organic Theatre, Barba’s reminiscence and associations with the colour yellow also seems to allude to the dark forces, both personal and collective, which shape and consume individual artistic destinies in unpredictable ways. More specifically, in the interview by Bandettini, Barba refers to the yellow fever in the performance title as ‘a creative frenzy’, recounting how in Europe by 1850 industries started to produce new colours for painters, such as yellow and violet, which could be stored in little tubes and used in the open air. Barba notes that the use of the yellow colour by the artists of that period becomes ‘a real fever’, which he compares ‘to the craving that social media has generated’ today. In the performance, the frenzy of the yellow fever becomes a celebration of being alive, almost a nervous excitement, an electric current between the performers and the spectators, and a vital impulse unleashed by the transformative potential of an extra-ordinary theatre happening.

As the programme says, the performance consists of twelve scenes, each titled to bring context to the course of events, such as Ritual of Purification (scene 1), Oedipus’s Spirit Wanders on the Battlefield Where his Two Sons-brothers Have Slain Each Other (scene 2) or Oedipus’s Spirit Reveals to Tiresias the Sense of Human Destiny (scene 4). The captions exemplify for the spectator the journey of a mythological man who will eventually blind himself in front of our eyes, to escape his sense of guilt, questioning ironically and in the cruellest way possible the purpose and nature of the human gaze. These cues not only guide our understanding of the unfolding dramaturgy, they also tell us that the appearance of the performers as myths is part of a ritual, of which we as spectators are holding the imaginative and interpretative keys. The descriptions work as a prologue, suggesting and provoking associations in the spectator’s mind ahead of witnessing the scenes. Yet, they are not spoiler alerts, like cinema trailers, as there is no expectation that we look for a representation of Greek mythology on the Odin Teatret stage. Rather, what is offered are narrative hooks, which entangle the imaginative power of the spectators with the evocative power of the performers’ embodiment, while suggesting that something of the live experience of a mythological world of violence and extremes we are about to engage with is not dissimilar to the malaise, brutality and societal crisis of our post-pandemic times.

In the foyer, Barba is standing on one side of the queue, smiling warmly to those who turn to catch his eyes. He is silently waiting and welcoming each one of his spectators, as he has done many times for the company’s ensemble performances, and the yellow fever is already amongst us, raising our collective temperature, while we are escorted to our seats by the front of house team. Once more in my life, I am stepping into the world of a theatrical myth, that of a theatre group who has managed to defy conventions, the tide of time, industry expectations, creative gatekeeping and artistic commodification with an unrivalled longevity and commitment to the profession and the craft. A theatre group who whilst developing an original performance aesthetic over the years has been capable of forming longstanding artistic alliances and relationships around the world, connecting with and supporting multiple international networks of independent (often marginalised) theatre groups, to whom Barba refers as Third Theatre.

There is a charged atmosphere of anticipation, while we are invited to take seats in a traverse stage configuration often used by Odin Teatret, which Barba calls the ‘river space’, allowing spectators to face each other while the performance happens in the middle, between, around and amongst us. This state of co-presence in a shared space with the performers provokes a sense of alertness and togetherness amongst audience members. It also adds an ethical dimension to the spectators’ gaze as proximity implicates us in the action.

Then in darkness reverberating with the warm light of portable lamps, Thebes at the Time of the Yellow Fever begins. Mindful of the explanation in the programme, I know that ‘it is the day after the last battle’ and that ‘the war between the two sons of Oedipus for the dominion of Thebes is over’. Figures wearing black robes, whose faces are erased by white fabric covering their entire heads, like bandages, enter one by one on the empty, feebly lit stage to perform a ‘ritual of purification’. They are the families who are burying the dead after the war is over, expressing their grief through battering and cleansing bloody stained white sheets in an invisible river to remove pain, guilt and remorse, while crying their horror and sorrow to the gods. The collective trauma of post-war destruction and desolation is played tenderly and with compassion, in the awareness that, as Barba indicates in the programme, ‘the figures of the Greek myths are action and energy. Their ferocity is not vile. Their suffering is not sadness. […] They don’t believe; they are aware. They know the Reality: the ineluctable power of those forces that we call Evil’.

Perhaps because I am conscious that I am attending the performance in Paris, I read these figures as a reference – if not an homage – to French actor, pedagogue and creator of corporeal mime Etienne Decroux, who opened his first mime school in the city in 1940. Transforming his Parisian home into a highly disciplined theatre laboratory in 1963, Decroux experimented with techniques such as erasing the face of the mime performer with masks and silk veils to increase the expressivity of the whole body. It is crucial to say that due to decades of cross-cultural pollination and exchange with Eastern and Western somatic practices, including corporeal mime, as well as with theatre pedagogies from around the world, what always stands out in the work of Odin Teatret is the incorporated technique of its performers. Individual training regimes and collaborative exploration through uninterrupted performance practice have been at the core of Barba’s empirical research, eventually leading to the creation of ISTA – International School of Theatre Anthropology – in 1979. As a field of study, theatre anthropology continues these days in its quest to identify shared techniques regulating performer behaviour across cultures, such as presence, which Barba refers to as the ‘pre-expressive level’ of the performer, a state which precedes any intentionality of meaning, character or representation.

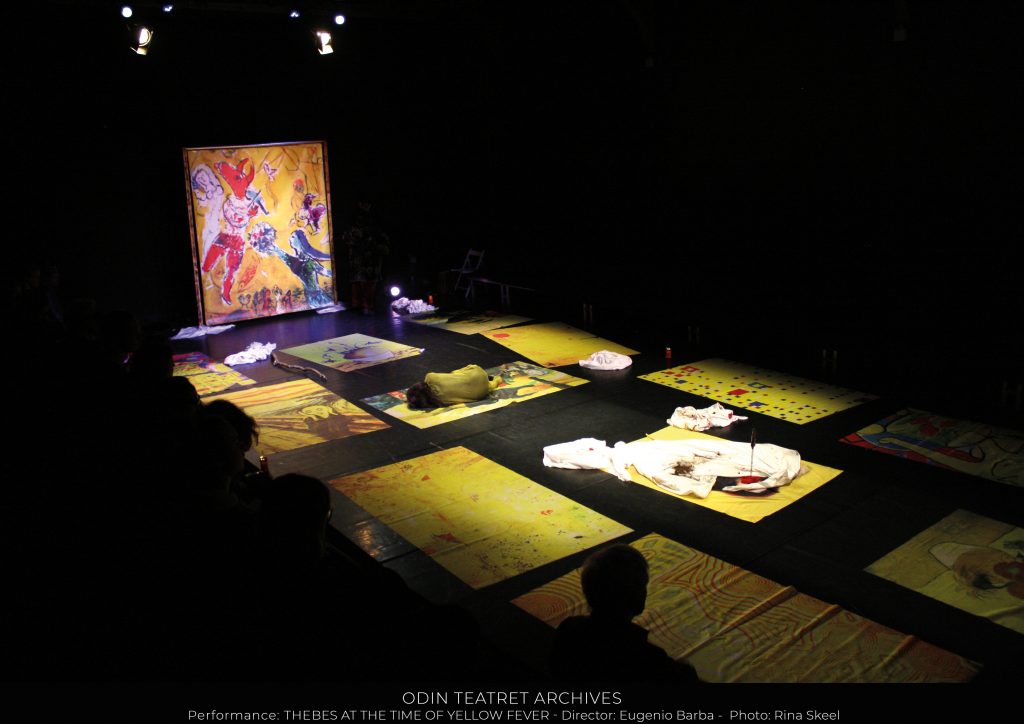

Almost unreal and without identity, the chorus of covered head figures in Thebes at the Time of Yellow Fever with their combined vocal and physical action generates musicality, rhythmic soundscapes and energetic ruptures, without (re)presenting anything other than its own flow. In scene 10, the ‘yellow fever breaks out’ and the mythological figures of Oedipus, Antigone, Creon and Tiresias spread over the river space, populating it with the ghosts of our civilisation, made of human-size canvases painted with replicas of famous artworks by Vincent Van Gogh, Edvard Munch and Gustav Klimt, amongst others. Unrolled and laid on the stage floor by the performers, the explosion of the ‘creative frenzy’ and of the yellow colour against the black minimalistic set is accompanied by the eruption of a cappella singing and is as vital as it is unsettling, like partaking in a display of mental extremes. The closeness of the performers’ bodies, their wisdom in the use of vocal resonators, and the immersive experience of Odin Teatret’s river space amplifies every whisper sneaking into our ears, while a soul-piercing choral song accompanied by the loud and forced sound of an accordion shakes the illusion that this is a distant society and an ancient world. Oedipus’s story cannot be told or understood without dealing with the brutality of our existence in close-up.

My kinaesthetic sense is moved in a space which is aurally and physically saturated by the bodies and voices of Bredholt, Carreri, Kitt, Rasmussen and Varley. In this sensorial journey, I am touched by what Barba in his introduction calls the essential, which manifests itself in ‘the bond-in-life between me and a handful of actors and a few spectators’ – a bond weaved ‘during a working process of months and months together with my actors who are also driven by blind and mute needs’. In Thebes at the Time of Yellow Fever, I am struck by the fluidity, subtlety and organicity of the performers’ dramaturgy and stage behaviour. These rest on a quality of embodiment built through decades of training, and through solo as well as ensemble performance making, resulting in a body language which is extremely precise and accurate, yet vibrant and translucent. As Barba points out in his interview with Bandettini, ‘it is not what you tell which is important, but how you tell it’.

Throughout the twelve scenes, I witness Odin Teatret performers radiate their individual Flower (Hana), a metaphor created in medieval times by Japanese playwright, actor and theorist Motokiyo Zeami, which is linked to the performance tradition and training practices of Noh Theatre, well known to Barba and Odin Teatret’s performers.

The Flower refers to a performer’s achievement not only in terms of their degree of virtuosity in the craft but in relation to their ability to attain transformative powers. At the highest level, which Zeami calls ‘the Miraculous Flower’, acting is perceived through the mind of the spectator, and not purely through the eyes or their other senses. Zeami refers to this as ‘acting beyond the mind’, when the performer is capable of defying the natural laws of time and space. This ‘mental’ acting allows performers to transcend the visible and audible, and to perform ‘miracles’. In Thebes at the Time of Yellow Fever the ineffable quality of the unique Flower of each Odin Teatret performer emanates through an exceptionally embodied knowledge of their craft. The rigorous technical work however remains invisible, while we are brought to a state of enchantment by a subtle manipulation of our imagination through almost otherworldly and rarefied physical and vocal scores. I am immersed in a performance which is not just a performance, as it empowers the spectators’ minds and associative capability, viscerally playing our inner human chords and opening the door to intuitive knowledge, rather than rational meaning – which, incidentally, is what myths do. As Barba elaborates in his interview for La Repubblica: ‘A performance can be illogical in conceptual terms, but has to possess a rhythmic and formal coherence which makes it believable to the nervous system and to the kinaesthetic sense of the spectator. In other words: a performance is dance, music and poetry, stimuli directed towards the senses, the emotions and the imagination of each single spectator.’

While the five performers regulate my experience of an elaborate and extremely refined montage, on the river space I witness the flowing of human fragility, greed, desperation, love, sexual desire and divination. Thebes exists and breathes as an organism, while the performance develops a pulsating heart, which alters my perceptions of space, raises my energy and transports my body-mind into another level of consciousness. In scene 12 – the final – titled ‘seven times Thebes will be destroyed and seven times plus one Thebes will rise again’, the purification rite of the beginning transforms into a clearing-up routine. The stage is dismantled and disassembled by the performers, who shift their physical scores into a light and springy dance, while simultaneously singing and folding each canvas. One by one, these are arranged to form a pile on a Thespian cart, and are covered with one of the bloodstained white sheets from the first scene, tucked in to seal off what belongs to the now consumed ritual of the performance. A severed bull’s head is placed on the sheet. The performers exit with nothing left in their hands, leaving the air in the theatre vibrating and transparent. Spectators remain seated, applauding an empty stage, as it is tradition in Odin Teatret that the performers do not take a bow. The bull’s head eyes, which can no longer see, reclaim my attention. A bright blue and cold light is still on the animal head, balancing on top of the red-stained sheet, as if the whole performance has been transformed into an installation, which contains both the abjection of a human sacrifice and the contagion of the yellow fever. I take pictures. Others do too. I remember Barba’s question ‘Should we not know ourselves?’. Just as in the ensemble performance Mythos, here too the myth of Oedipus seems to advise ‘tear out your eyes, so you will see the story in the light of your memory’. Life is our enigma. As long as we have the stamina, we will try to find an answer, after which what remains is the contemplation of what has been, in all its beauty and cruelty, for those who wish to remember.

As Barba explains on the new Odin Teatret website, separating from the Nordisk Teater Laboratorium ‘was due to the artistic choices and organisational transformations of the new director and the board of directors’, whose ‘way of thinking and realising theatre diverges fundamentally from the ideals and work culture that have characterised the identity of Odin Teatret as a theatre group’. While it is emotionally and practically difficult to disentangle the rich and vast history of the company from the physical buildings Barba and his ensemble created, departing from Thebes towards new adventures, Odin Teatret’s activities continue and the calendar is buzzing. In May 2023 the 17th session of the International School of Theatre Anthropology / New Generation, titled ‘Pre-expressivity – composition – montage’ will take place in Budapest (Hungary). The research gathering will conclude with Anastasis/Resurrection, a new performance devised and directed by Barba and performed by the artists/teachers and by the participants. This session of ISTA/NG, like the previous one in Favignana in 2021, is part of the core project of ‘sharing knowledge’ initiated by the Fondazione Barba Varley, which was created by Eugenio Barba and Julia Varley in 2020 with a special focus on memory, sustainability, and solidarity. The project also includes the open source publication Journal of Theatre Anthropology, alongside video resources on theatre anthropology and the techniques of the actor/dancer which can be downloaded for free from the Fondazione website.

Another core mission of the Fondazione is to support through annual financial awards the submerged theatre culture of those who Barba calls the ‘nameless’ – that is, the theatre and socio-cultural groups in emergency and marginalised situations ‘who perform particularly important work in the field of human rights’.

The past, present and future of Barba and Odin Teatret is also converging in the project of the Living Archive Floating Islands (LAFLIS), inaugurated in Lecce (Italy) in October 2022 as a partnership between Fondazione Barba Varley and Regione Puglia. The archive will be focused on memory, transmission and transformation and will be dedicated to the promotion, research and study of the history of Odin Teatret, Eugenio Barba, and Third Theatre, the international culture of theatre groups.

While the work continues relentlessly, on the company’s social media posts one statement for me beautifully encapsulates the power and unshakeable vision of ‘a group of actors who have been working together with the same director for sixty, fifty, forty years, which has never happened in the history of theatre’ as Barba says to La Repubblica.

No longer with a fixed base, the group who – in the words of Odin Teatret’s founding actor Else Marie Laukvik – ‘invented the training, invited [Jerzy] Grotowski and his theatre abroad for the first time, published a pan-Scandinavian Theatre journal, and organised seminars’ during its early years, now leave the following metaphor through its digital footprints for us all to consider: ‘Odin Teatret’s journey continues toward a house, which is all the houses scattered in every corner of the planet they’ve stepped foot on – the home of their legacy.’

For more on Odin Teatret and their legacy and plans, see: https://odinteatret.org/

For the Fondazione Barba Varley, created by Eugenio Barba and Julia Varley in 2020, see: https://fondazionebarbavarley.org/

Featured image (top of page): Odin Theatret: Thebes at the Time of Yellow Fever. Actors pictured: Roberta Carreri, Iben Nagel Rasmussen and Julia Varley. Photo Rina Skeel

Odin Theatret: Thebes at the Time of Yellow Fever was presented at La Cartoucherie de Vincennes, Paris

Bianca Mastrominico attended performances on 11 & 12 November 2022

Odin Theatret: Thebes at the Time of Yellow Fever – Full Credits:

Director: Eugenio Barba

Assistant director: Dina Abu Hamdan

Actors: Kai Bredholt, Roberta Carreri, Donald Kitt, Iben Nagel Rasmussen, Julia Varley

Scenic space: Odin Teatret

Light designer: Fausto Pro

Light designer supervisor: Jesper Kongshaug

Costumes and props: Lena Bjerregärd, Antonella Diana, Odin Teatret

Visual art advisor: Francesca Tesoniero

Poster: Peter Bysted

Musical director: Elena Floris

Photo: Rina Skeel

Dramaturg: Thomas Bredsdorff

Advisors: Gregorio Amicuzi, Juliana Capilé, Antonia Cioaza, Tatiana Horevicht

Special advisors: Nathalie Jabalé, Ulrik Skeel

Bianca Mastrominico is a performance maker, writer and director born and trained in a well-known theatrical family in Italy, who founded and ran their own company and theatre in Naples from 1972 to 2013. Since moving to the UK in 2002, she has been co-artistic director of the performance laboratory Organic Theatre

Currently Bianca lectures contemporary performance practices at Queen Margaret University in Edinburgh, leading the BA(Hons) Performance and MA Digital Performance courses. She is also co-leader of the Practice Research cluster within the Centre for Communication, Cultural and Media Studies, and has presented her creative work and practice research widely, both in professional and academic contexts.

Bianca is a member of the Magdalena Project network of women in contemporary theatre and has published for Total Theatre Magazine, The Open Page, Journal of Theatre Anthropology, New Theatre Quarterly, Body, Space and Technology, International Journal of Performance Arts & Digital Media, amongst others.