Bloodthirsty buffoons, a giant snail, a pit of fire-breathing snakes, an invisible orchestra, and a troupe of death-defying showwomen: Out There International Festival of Outdoor Arts and Circus 2024 had something for everyone, as Dorothy Max Prior discovered. Additional reporting by James Foz Foster

It’s the first night of Out There Festival 2024, and although this is predominantly an outdoor arts festival, we are indoors, in the Hippodrome, Great Yarmouth’s legendary purpose-built circus venue. It’s a beautiful space – even the toilets are beautiful, with their red-painted doors plastered with old circus posters in glorious technicolour. It’s ten minutes before the first show of the Festival, and there’s a buzzy crowd taking their places in the rows of red velvet seats rising up in steep tiers from the ringside.

So yes, we are here for a circus show, of sorts. But it’s not a run-of-the-mill one – there’s more here than mere tricks and turns (although there are plenty of those too). The show – merging theatre, circus, and performance art – asks: What happens to the showgirl when she grows up?

The answer, ring-mistress Marisa Carnesky tells us, is that she becomes a showwoman – with two ‘w’s, one for the ‘show’ and one for the ‘woman’. A showwoman, we learn, is ‘showing herself because she wants to’. And, vitally, ‘she never misses a show’.

Showwomen has been researched and directed by Marisa Carnesky – who was initially inspired by her trips to the National Circus and Fairground Archive in Sheffield – and created in collaboration with three others: performance poet and sword artist Livia Kojo Alour, ‘fire lady’ and suspension artist Lucifire, and Veronica Thompson, aka hair-hanger extraordinaire Fancy Chance. For the Out There Festival performances, Marisa, Livia and Lucifire are joined by aerialist and hair-hanger Jackie Le in place of Veronica Thompson, who has commitments elsewhere.

In the show, the contemporary performers explore their own showwomen circus and sideshow practices with reference to the legacy of forgotten and marginalised female British entertainers. Before we get going on the individual stories, there’s a nice little ensemble scene in which our showwomen act out a medley of telephone enquiries. They state the nature of their acts, their price, and their conditions of engagement. A repeated mantra emerges: ‘No, I don’t do that – but I know someone who does.’

The show weaves fabulous individual circus acts and death-defying stunts with autobiographical revelation, vintage film footage and stills, and musings on the historic showwomen that each have forged a connection to. There’s a gorgeous aerial hoop routine by Jackie Le, who is of Asian heritage, to the tune of Mae West singing, ’I’m an occidental woman in an oriental mood for love.’ All irony fully intended. The historic 1880s teeth-hanging aerialist superstar Miss La La is referenced in the show, although we get hair-hanging from Jackie rather than teeth-hanging, a truly treacherous practice! Marisa, replete in a pomposity of pom-poms, summons up the spirit of 1930s clown Lulu Adams. Livia – formerly a sword-swallower, but now confining herself to (merely) walking on blades and (gasp!) broken glass – channels the 1940s circus star and fakir Koringa, who may or may not have been Black – exploring the dubious heritage of the exoticised Black female body in circus and cabaret. Lucifire whip-cracks-away with breathtaking skill, repeatedly breaking the sound barrier in homage to 1950s Western skills performer Florence Shufflebottom, a sharpshooter and snake-charmer who started off in the family business as part of her father’s knife-throwing act, aged just 5 years old.

And here’s a thing: in the audience tonight are members of the Shufflebottom family, including Florence’s son! The family’s contribution to the post-show discussion adds a wonderful poignancy to the evening.

It’s a fabulous show, merging all of its various elements seamlessly to create something that is both an exposition of top-notch circus skills and a deconstruction of those skills; alongside an exploration of where the contemporary showwoman is placed in relation to the history of circus and sideshow. Why do women continue to put their bodies and themselves on the line in the name of entertainment? And are we still willing to break taboos? We return again and again to those two key maxims: She is showing herself because she wants to. And she never misses a show. The show must go on…

With the change of dates of Out There to the end of May, it is the Festival’s intention going forward that they have a show in the Hippodrome each year. And with a new circus and arts centre, the Ice House, opening at the 2025 festival, there will be an increase in indoor programming for the Festival from next year onwards. But for this year, the outdoor work remains at the heart of the festival, although there is also the usual programme of indoor shows and activities at the organisation’s headquarters, The Drill House.

This year, Friday and Saturday were the key days for the outdoor programme, rather than the usual Saturday and Sunday of past years – with the Party in the Park nights kicking off on Thursday evening. As it was spring half-term holiday, Friday and Saturday saw the main sites for the shows – St George’s Park, Trafalgar Road and the Marina Centre Car Park – packed with family audiences out and about despite the squally weather. Thankfully, regardless of wind and occasional spots of rain, all shows went ahead, and a good time was had by all. Also, the move to late spring meant extended daylight hours – so shows continued well into each evening.

As always, the work presented was an eclectic mix of the traditional and the experimental – and much that, like Showwomen, merged the two. There was street theatre (some static and some promenade), circus of all sorts, dance, music, comedy, interactive game-playing – and some boundary crossing shows difficult to categorise!

Out There Festival has always been a strong supporter of street theatre of all sorts, from the traditional character-comedy shows that England always seems to have done well, to the more experimental imports (often from France).

In that first category came Festival favourites Cocoloco, who took to the streets with Mafia Wedding, a promenade show which tells the tale of a mafia boss with a pregnant daughter in urgent need of a groom (not to mention a bridesmaid or two, a priest, and a congregation) for a shotgun wedding. The show has been in the company’s repertoire for quite a long while as a two-hander, but here is given a makeover, with local community performers and students (many of whom took part in last year’s Cocoloco show, Shangri-la-la) returning to swell the ranks of the wedding party, resplendently dressed in pin-striped suits and furs, high-heels and hats. Cocoloco’s Trevor Stuart – whose longstanding and noble street theatre heritage includes many years with The Natural Theatre Company – was clearly born to play the mafioso father of the bride; and partner Helen Statman’s nine-months-pregnant Maria is a superbly pitched character. The shockingly hilarious ‘waters breaking’ scene in the middle of Yarmouth’s busy Trafalgar Road will stay with me a long time. And I did so enjoy dancing The Godfather waltz…

Also homegrown, and also a promenade piece: Jones and Barnard took us on their Golden Tour along the seafront drag, aided and abetted by another street theatre veteran, Paschale Straiton – who comes with excellent credentials, as her company Red Herring have created more than one fabulous performance-guide to a seaside town!

We gather at the Marina, and are issued with colourful parasols, which we are instructed to wave in the air with gay abandon. The gaudy parasols are a nice touch, uniting us as a group, inviting amused glances from passers-by. Matt Barnard, dressed in a luscious violet velvet suit and a cheeky little hat, is our principal guide (or perhaps that should be mis-guide) – although he does pass the baton to the other two along the way. Gareth Jones and Paschale employ quick-change strategies to play a number of different characters, channelling Great Yarmouth’s history, real or imagined. Thus, Paschale morphs from Trixie Tarot the flouncy fortune-teller to a beard-stroking Charles Dickens who apparently lived locally for a while; whilst Gareth plays ‘Jerry’ – the whole of the Luftwaffe, no less – who bombed the local sea defences before being seen off by Dad’s Army, later becoming an amalgam of two famous local divers, our plucky performer taking an almost-naked dive into a bucket of cold water, assisted by a posse of strong men drawn from the audience. No mean feat in the low temperatures of the day, with the North Sea winds gusting! At one point on the journey, Matt disappears to re-emerge in wig and frock at the door of old music hall The Empire, having transformed himself into locally renowned opera singer ‘Lily’. We cross the road from The Empire to the seafront lawns, the other two joining ‘Lily’ in a fabulous rendition of Gilbert & Sullivan’s Mikado hit ‘Three Little Girls From School Are We’. The trio then morph into rappers to big up the history of the Ice House and sing the praises of Yarmouth’s ice cream parlours (nice link there, lads and lassie). Jones and Barnard’s obvious parallel with Laurel and Hardy, in body size and master-and-servant clown roles, is honoured, as the two give us a Stan and Ollie song-and-dance number outside Britannia Pier.

It’s a show full of brilliant ideas, with very many great vignettes – although some scenes are stronger than others. The pace is a little wonky, and it needs a fair bit of ironing out, but it is important to acknowledge that it’s brand-new, and with this sort of work – promenade in public space with numerous interactions and costume changes – there is no real way to rehearse it other than to do it. It is site-specific to Great Yarmouth, so it’s not as if they could easily transpose it elsewhere and get the usual bedding-in that new street theatre shows receive in the summer season. But as it is full of potential and so clearly belongs here in Yarmouth, let’s hope Out There bring it back next year with more development time beforehand – it certainly deserves that!

Fraser Hooper brings us a very different sort of clowning to Jones & Barnard’s cheery repartee – solemn and silent, for the most part. He’s to be found Lost in St George’s Park, wearing a ridiculously over-sized backpack, carrying a map and looking bemused. Where is he trying to get to? Does he need help? As he turns the map around, he spins 180 degrees and careers into passers-by. Some people laugh, some look cross, some try to ignore him – which is ridiculous. How can you ignore a man with a backpack so big it takes up the width of the path? At one point, the silent mime speaks: a woman points out that his map is of the Lake District so not much use here in Yarmouth. ‘It’s the only one I have,’ he says with a sad shrug before moving on….

And yet more clowning, of another sort: comedian Paul Currie works a seafront crowd with fabulous skill and enormous energy. Objects play a key role, as Currie riffs wildly on one theme after another, moving on at a breathless pace. Gloves and glove puppets singing “She Gloves You’ and ‘Glove to Glove You Baby’. A boomerang croc shoe. A toy dog stuck onto a keyboard (‘the huskeyboard’). Sometimes no props are needed, it’s just his delighted delivery and our imagination that does the work: ‘the middle aisle in Lidl’ is enough to provoke roars of laughter, as is ‘asparagus pee’. He takes requests, and we end riding invisible dragons in tribute to The NeverEnding Story. A true clown – so upbeat and uplifting, and so very, very funny.

Over to the other end of the spectrum now, the darkest of dark humour, and an edgy French troupe called Compagnie Têtes de Mules (the Company of Mule Heads!) who brought us Parasite Circus, in which a bolshy female bouffon and her sulkily subordinate male companion torture and mutilate a whole troupe of puppet circus characters, all of whom have fabulous names (Pinky Bunny is a favourite). Our two bloodthirsty clowns start on the roof of their decrepit caravan, playing a broken accordion and the strangest looking tuba ever seen, heralding a show score with echoes of Carlos d’Alessio’s soundtrack to the film Delicatessen. They descend, mock the audience, conjure up the puppet performers, and the mini splatter-fest begins. Le sang! Le sang! Bring on the blood! A bendy box splits goes too far, until the poor creature is mercilessly rent asunder, an aerial rig becomes a gallows, and as one unfortunate after another meets their fate, puppet guts splatter the audience. Then, the ripped and torn remnants are unceremoniously binned – accompanied by demonic laughter. I have no idea what the company’s provenance is, or where they trained, but their classic bouffon techniques of laughing unashamedly at ‘death, fear, disease, difference and deformity’ courting a ‘desecration of common sense and the idea of political correctness’ are very much in the tradition of the work of Jacques Lecoq. Grotesque burlesque to the nth degree – a gruesome, carnivalesque success.

There’s most definitely a circus-sideshow vibe at this year’s Out There Festival, and this is echoed in Ava-go-go-ville, a mini festival within the festival on Trafalgar Road, between park and seafront.

Within this site you’ll find a bar and numerous sideshow attractions, including Professor WM Bligh’s Circus Photo Tent, which invites you to have your picture taken as a circus act – be it knife-thrower, strongman, or trapezist; Willow Phoenix: Electric Hamster Racing (‘time to get competitive, only the fastest hamster will win’); and the Hocus Pocus Unsolicited Advice Bureau caravan hosted by self-discovery gurus ‘Tony’ and ‘Pam’ who are offering Speed Life Coaching and Public Art Therapy. There’s also the ever-popular The Loser’s Arcade – a phantasmagoria of ridiculous neon outfits, and ludicrous games (‘Roll up, roll up – everyone’s a loser!’). A favourite game features children racing in imaginary creature outfits, accompanied by the wonderful Ernesto on trumpet who plays joyfully out-of-tune accompaniments to the music drifting in from the seafront arcades. It all fits in perfectly with the Great Yarmouth seafront vibe, being loud, tacky, glittering and life-affirming. You can’t help but come out giggling.

Returning at night to Ava-go-go-ville, we encountered Paka the Uncredible’s Bag of Snakes, which has a loose connection to Paka’s ongoing interest in addressing the bad image Medusa has received over the years. This theme will manifest more in future developments: for now, Bag of Snakes is presented as a fun fairground activity – an ‘interactive pyro-kinetic, addictive and dangerous game experience for all shoe sizes’. It’s a take on the popular mole-thumping challenge – in this case, the ’snakes’ in the pit, known as The Medusa Misfits, light up, hiss and spit fire as contestants bash away at ever-faster-changing coloured pads. Great fun! Another night-time hit in Ava-go-go-ville is Miniscule of Sound’s The World’s Smallest Nightclub, which is exactly what it says on the tin – as close to a London clubbing experience as you’ll get inside a tiny booth with room for four people. You walk down a red carpet to be met by mirror-shaded bouncers and then led in to the soundproofed box with a live DJ behind glass in his booth, cheering you on. There’s very loud classic club anthems, and just about enough room to dance ecstatically. A joyous experience.

Elsewhere, live music played a key role in this year’s Out There Festival, with styles ranging across a full spectrum: crowd-pleasing party favourites and cover versions; rousing gypsy jazz, ska, and funk; and inventive, wonky, hauntological music made from found objects and played on old broken instruments… Talking of which, here’s Eric Tarantola and his Imaginary Orchestra – seen indoors at the Festival launch at Drill House on Thursday evening, and outdoors on Friday and Saturday. Eric is a tall Frenchman with a wild hairstyle, a gentle mime-clown who plays a homemade guitar/ banjo double-neck and a junk shop old trombone; these looped with the sound of wind-up clocks, metal cutlery and other random objects, which provide a percussive rhythm accompaniment. As the show progresses, he picks up an old mechanical clock from inside a battered suitcase and turns it around to reveal he has integrated a kalimba into the back, allowing him to play a melody to the clock’s beat. Very charming, very French – and like the aforementioned Parasite Circus, reminiscent of the films of Jean-Pierre Jeunet, as soundtracked by Carlos d’Alessio.

Still on the ‘wonky with homemade contraptions’ side of things come Rimski & Handkerchief with An Afternoon Out. Rimski sits on his Bicycle Piano, an old piano bedecked with artificial flowers, horns and hooters that is attached to a chain-driven tricycle base, pedalling the piano up and down paths and managing some very tight corners. Handkerchief plays the Double Bassicle – which is, as you’d imagine, a similar contraption for her double bass. They sing and play a medley of whimsical old songs: ‘I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire’ and, as the dark clouds gather above our heads, ‘Stormy Weather’. At seemingly haphazard moments, they change and shift direction. There are unexpected musical stops and key changes – the pair sometimes shifting in and out of the familiar melodies into (possibly) their own compositions, all perfectly timed to the stop-start and direction changes of their pedalling. Even when they sing ‘It’s Time to Go’ they are followed along the way by a smiling crowd who are ready to give them a push if they get stuck in a pot hole.

A firm favourite of many festivals is the musical walkabout troupe playing Eastern European influenced gypsy jazz and ska. Enter Portuguese troupe Kumpania Algazarra, the ensemble featuring a winning combination of trumpets, tuba, electric guitar and bass, drums and percussion. They were kept pretty busy throughout the festival. Wearing matching coloured hoodies and shades, they processed along the seafront, gathering a large and enthusiastic audience along the way. They played the park stages; they led off the Grand Finale procession; and they entertained at the late-night Festival Lounge at The Drill House. It was impossible to miss them! They are great musicians playing tight, funky versions of classic hits and Eastern European and Latin standards, interacting well with their audience – a definite crowd pleaser.

Another crowd-pleasing act is Loveboat – inspired by the TV series of the same name, and featuring two men dressed in short-sleeved merchant navy outfits, one playing keyboards, the other singing and occasionally playing guitar to backing tracks of rave/disco bangers, with a touch of 80s easy listening cheese, all accompanied by over-the-top dance routines and flashing disco lights. Loveboat is a heady brew, evoking a disco party night on a Mediterranean cruise ship featuring exotic cocktails. Like Kumpania Algazarra, they certainly sang for their supper: they played the main music stage in Party in the Park, a small intimate set in Ava-go-go-ville, and entertained the late-night revellers at The Drill House.

A thumbs-up too for the Young Out There (YOT) musicians, who had their own stage on one side of the park, but also took over the main stage now and again. Some of the acts we caught included Oasis-inspired Parallax, head-banging rockers Kuiper, and alt-rock/punk band Amourette. All three had endless energy, and held the crowd’s attention throughout their sets – and it was good to see the young bands take to the main stage with confidence, with such a supportive local crowd to-hand. One YOT act we sadly missed was Terran Burrell, who plays Shruti box, blending its drone sound with vocals to create a neo-folk set – with a few video game soundtracks blended in, apparently! But good to learn that there are young people out there at Out There choosing more unusual musical instruments and influences.

Music also, quite naturally, played an important part in many of the dance shows seen. Vanhulle Dance Theatre’s Olive Branch is performed by two martial-arts trained contemporary dancers who balance on roughly-hewn logs, playfully demonstrating a need to work together – there’s a message there, for sure. They merge expert equilibrist skills, stunning martial arts moves, smooth contemporary dance/contact duets, and gentle clowning to create an enjoyable and well-received show – which was developed in Yarmouth at The Drill House, with the support of Out There Arts. The music, composed by Italian jazz guitarist Domenico Angarano (who has previously worked with renowned choreographers Akram Kahn and Hofesh Schechter), was the perfect accompaniment to the skilled physical performance.

An unexpected delight of the 2024 dance programme, also featuring a great musical score, was a small but perfectly-formed piece by two teenage artists, collectively known as Stacked Wonky, who hail from rural Somerset. 4 Minutes starts with our young male performers approaching from afar, walking down the centre of the road carrying chairs. These are placed behind a wooden table stood in the middle of the street. There follows a breathtaking ten minutes of beat-the-clock game-playing, alternating between collaboration and competition as the table is laid upon and leapt over, chairs spun like skipping ropes to be hopped over. In quieter moments, a gestural dance-theatre vocabulary of ticks and touches and shrugs is played out, T-shirts pulled up over heads, small glances exchanged. It’s a truly lovely piece of dance-theatre work, with the added bonus of a great live music accompaniment, featuring the beautiful electronic looping viola of Argentinian composer and multi-instrumentalist, Sebastian Tesouro.

Collectif Bim’s Place Assis (which translates as ‘a place to sit’) is a non-verbal performance set on a public bench. It’s a well-played piece of ensemble physical theatre, with the five performers imaginatively transforming the aforementioned bench into a car, boat or horse. There’s a fair bit of ‘school’s out’ type romping, with bags stolen and chucked around, and a lot of pushing and shoving and chasing round and round, all cleverly choreographed. It’s not going to change the world, but it’s a fun piece of work that goes down well with the audience.

Gorilla Circus are best known for their aerial work, but for this edition of the festival, they presented RPM – a dance, acrobatics and rollerskating piece set on a moving treadmill. Because of the unseasonably cold weather, it did feel hard to stay still and connected for a 45-minute-long static show, on in the park at 8pm. That said, the section seen (before the cold got too much, sending us scurrying to The Drill House) was a breathtaking display of acrobatic skill and co-ordination. And Gorilla Circus are to be applauded for trying something that’s new to them. There’s also the need for companies to produce work of different scales for touring – and as so much of their repertoire is large-scale, requiring a lot of rigging space, here’s a show that is more easily tourable, suitable for indoors or out.

Other circus companies seen at this year’s festival included Belgium-based 15Feet6 with Primus, a collaboration between Finnish Cyr wheel specialist Rosa Tyyskä, and the equally skilled Belgian Jasper D’Hondt who specialises in acrobatic bicycle and roller-skating. The 2020 lock-down forced the couple off the international touring circuit and into collaboration with each other – Primus being the result. And what a result – it really is a gem of a show, exploiting the performers’ skills beautifully.

The pair are dressed in a kind of neutral school uniform (grey shorts/short skirt with white shirts) and the show plays out a love-hate competitive schoolyard friendship, starting slowly and building beautifully. In the beginning, they work the crowd, with two young volunteers co-opted to give out raffle tickets for a school-fete style tombola, the draw of which goes with a bang (literally). In a kind of parody of playground tactics, they each demonstrate their respective skills – aided, abetted or undermined by the other. Rosa zips around with extraordinary ease on her Cyr wheel; Jasper counters with a mocking hula-hoop act. Jasper hops on his bike and demonstrates some fabulous tricks; Rosa leaps on with him, shoving her behind in his face, or jumping up on his back. After lots of running jokes about their roller skates (Jasper’s are almost given away by Rosa in the tombola!), they don their wheels for a superb roller-skating doubles finale – fantastically fast and furious, demonstrating wonderful partner work, all rivalry now dropped and everything all about the two working as one. Primus was certainly one of the outstanding shows of Out There 2024.

More rollerskating: Dulce Duca’s Unstoppable at first purports to be a one-woman show. Duca, resplendent in an extraordinary purple tulle outfit, channels her inner diva, strutting around full of herself and her accomplishments, demonstrating her club-juggling and roller-skating skills, and building a brilliant repartee with her audience – the juggling challenged a little by the fierce winds blowing, but she overcomes all obstacles. All obstacles, that is, except a late-arriving audience member who walks across the performance space and fussily seats herself, arranging her shopping trolley by her side. Then the fun and games start, as the annoying woman (who we soon realise is a plant – played by actress Tsubi Du) starts to disrupt the show – subtly at first, but later running into the space to grab clubs and jam them into her trolley. It all gets more and more farcical, and builds to a suitably ludicrous climax, with Duca and her combatant finally united in a ritual task – the funeral for the broken clubs. Unstoppable is a very sweet play on the challenges of performing outdoors, a space where anything can happen and probably will – wild winds, squally showers, dogs on strings, drunken old geezers, mouthy teens, crying babies, and bolshy old ladies with shopping trolleys disrupting the space! Street theatre queen Dulce Duca sees off all disruptions and reigns supreme. A master (or is that ‘mistress’?) class in crowd control.

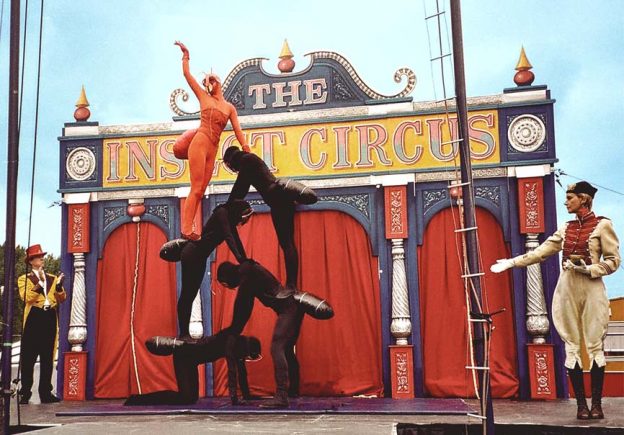

Finally, we come to the The Final Grand Finale – the very last shows ever for local heroes The Insect Circus.

The Insect Circus was created by partners in life and work, Mark Copeland and Sarah Munro. The project has seen many incarnations, from painting exhibition, to travelling museum, to indoor show, to outdoor show. Very many different circus artists have been involved over the years and many are back for the grand finale – the show has been revived after a five-year hiatus, to be retired again after the Festival, this time for good!

So here we are: this is the end.

This incarnation of the show has a cast of 25 drawn from across the country, and indeed from across the world. Many of the old favourites are back. Pippa Coram (all the way from Australia) is the hula-hooping Albina the Awesome, accompanied by a brace of lurid green praying mantises. Simon Deville is Western skills maestro The Great Flingo, pinning the poor unsuspecting butterfly to a board to the tune of the ‘Bonanza’ theme tune, and ‘Don’t Hem Me In’. Marcos Rivas Farpon is Mr Maroc, taming the wild and beastly Sylvester the Stag Beetle with a dash of classic matador Paso Doble, assisted by Flamenco dancer The Delightful Dolores. Phoebe Babette Baker performs as Phee and her Bee on the tightwire (when the wind dies down for long enough, anyway); and Ashling Deeks brings Dungo the balancing scarab beetle out of retirement. Dungo’s trainer, Peggy Babcock IV, is played by Persephone Pearl, who also reprises her turn as the back end of a pantomime horse (at least, I think it’s her in there – it’s hard to tell). But there is also the next generation: aerialist Vicky McManus is returning with her daughter Saskia Poulter for the Mothball Bolero and other aerial acts; and two of the younger members of the team play aerialists Molly and Dolly Lollipop, performing a very lovely doubles hoop act. Mark is ringmaster, pulling it all together, and Sarah plays Nursey, on hand in case of insect bites and stings (Pemma Ricardo, aka Constance Courage, keeps control of the Vicious Vespa Wasps, but they have been known to run amok). Nursey also does her own short act as a warm-up before the main show – The Mighty Mites Tea Party, a fabulous little puppetry show in which the eponymous mites behave very badly indeed.

We must also give a mention to the fabulous Sybil the Snail, a giant beast who, unlike the other creatures of the circus, will possibly not be sent off to be cryogenically frozen in A(n) Ice House, but will live on as the Out There Arts mascot…

It was Sybil who led off the grand parade for the Community Carnival on Saturday evening, in celebration of the Ice House, and honouring 20 years of The Insect Circus – a wonderful finale to Out There Festival 2024. The Festival’s musical troupes, including Kumpania Algazarra and classical string-quartet Bowjangles, joined forces to provide a rip-roaring live soundtrack; artists and volunteers at the Festival processed from The Drill House to the park waving colourful flags; and The Insect Circus creatures took their final final bows before being ceremoniously retired, leaving the children and grandchildren of the company in the ring hula-hooping.

Perhaps, muses ringmaster Mark to us afterwards, the grandchildren will one day take up the baton and ‘unfreeze’ the insects. Until then, it’s the end of an era for The Insect Circus, but the start of a new one for Out There Festival – the Spring slot having been well and truly christened.

The show must go on, the show will go on – here’s to May 2025!

Featured image (top): Compagnie Têtes de Mules Parasite Circus. Photo James Bass Photography

This year’s edition of Out There International Festival of Outdoor Arts and Circus ran 30 May to 1 June 2024.

More About Out There Arts – National Centre for Outdoor Arts & Circus

Great Yarmouth based, but collaborating internationally, Out There Arts – National Centre for Outdoor Arts & Circus is a registered charity and Arts Council funded National Portfolio Organisation dedicated to supporting excellence in the development, creation and presentation of new and high quality artistic work, delivery of outstanding circus and outdoor arts festivals, and events for and with diverse local communities and wider audiences.

Out There Arts shares Great Yarmouth’s vision to become the UK Capital of Circus. Their focus on circus and outdoor arts grows naturally from this seaside town’s rich performance heritage, providing an accessible medium to support their work.

Fresh Street at Out There Festival 2025

Fresh Street – The International Event for the Development of Outdoor Arts is back for its fifth edition on 28–30 May 2025. This flagship professional meeting bringing together key European and international players, artists, programmers, producers, researchers, and policy-makers from for three days of dynamic discussions and stimulating exchanges on how we can imagine the outdoor arts of tomorrow.

Fresh Street #5 is co-organised by Circostrada Network and Out There Arts in the frame of Out There Festival, in partnership with Outdoor Arts UK.

https://www.circostrada.org/en

More About the Ice House

A Grade II listed building of brick construction with a thatched roof, the Great Yarmouth Ice House, once one of a pair, is now the only one of its kind left in the country.

Out There Arts have a vision to transform it into a National Centre for Outdoor Arts and Circus. This imaginative and creative use of the building will further develop the town’s reputation as the capital of circus in the UK as well as further link the town’s fishing and circus heritage.

All funding is now in place, with the project supported by the Architectural Heritage Fund and the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Arts Council England, Great Yarmouth Borough Council, and the building’s former owners Towns Deal Brineflow.

Capital works began in February 2024, and is scheduled for completion in March 2025, in time for Out There Festival 2025.

The Insect Circus Museum

The show may be finished, but The Insect Museum lives on! Now in permanent residence at a house in Great Livermore, Suffolk IP31 1JN. Visits by appointment. Contact Mark Copeland on: theinsectcircus@gmail.com