What makes Catalan performing arts so special? Dorothy Max Prior reflects on the rich tradition of circus, outdoor arts, and site-responsive performance by artists from Catalonia

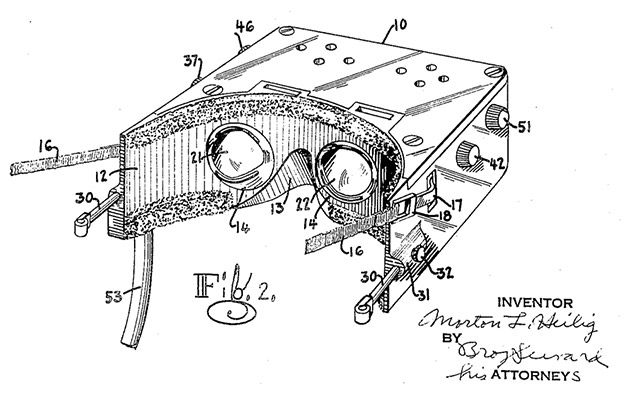

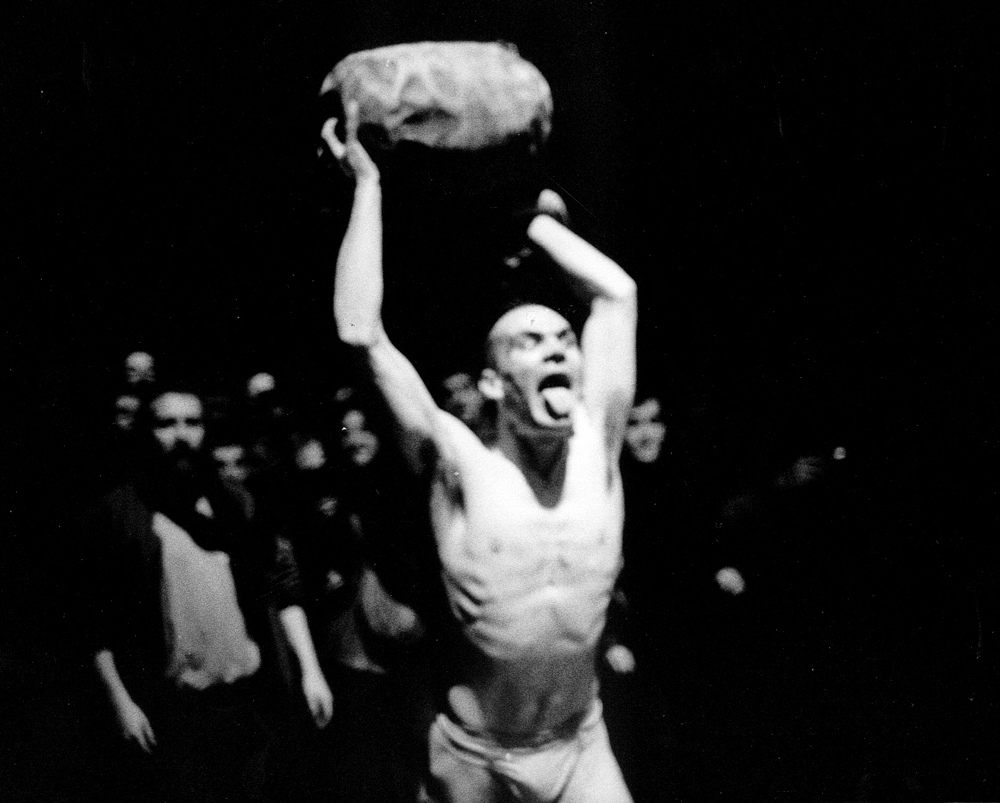

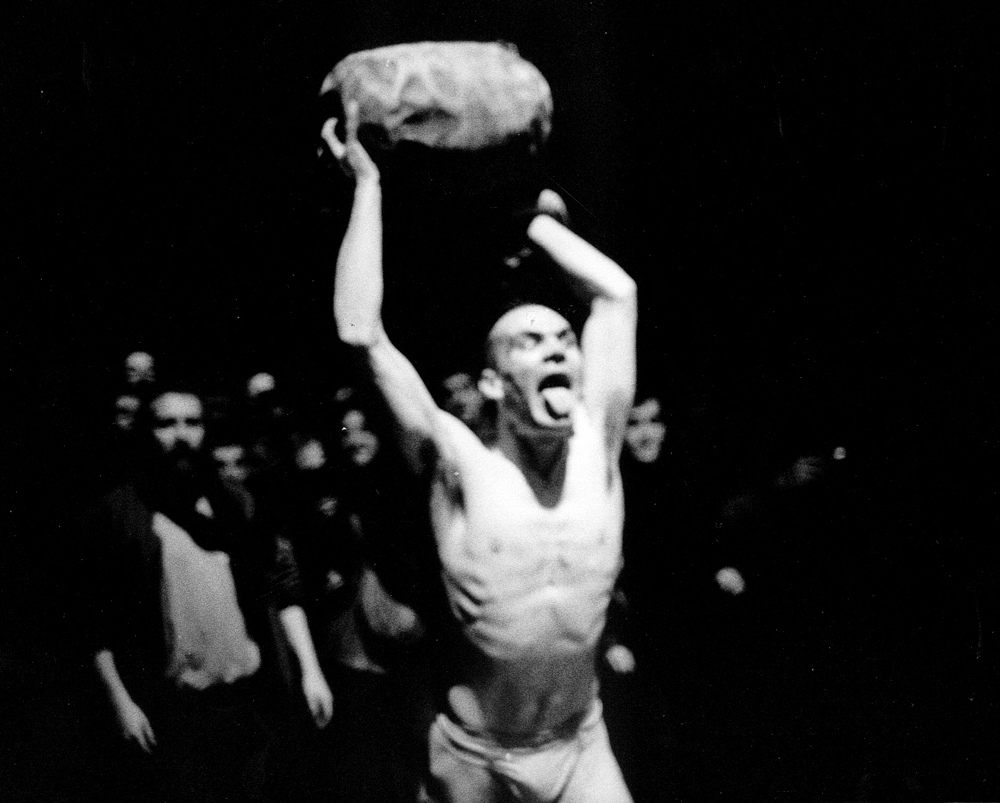

I’m trying to remember the first time I saw – or consciously recognised that I was seeing – work by a Catalan company. I think it must have been La Fura dels Baus’ 1985 UK debut in a warehouse in what was then a run-down part of London’s docklands. The show was called Suz/O/Suz, and a review in music paper NME described it as ‘a kind of adult adventure playground of fun, danger, slapstick and fantasy’. There was no stage, no separation between the audience and the performers, who emerged from nowhere, naked, breaking eggs over heads, beating on barrels, wheeling preposterous hybrid metal carts into the fast-scattering audience members, setting off fireworks, and climbing walls like unleashed lunatics. I remember my delight and astonishment at seeing something so raw and wild, a show in which experimental music (mixing live and electronic instrumentation) provided the soundtrack for such extraordinarily visceral physical action. La Fura established their own, and Catalonia’s, reputation as creators of anarchic multi-discipline performance that challenged conceptions of what ‘theatre’ could be.

La Fura dels Baus: Suz /O/ Suz, 1985

Sometime after that, I came across Els Comediants (under the direction of Joan Font), whose masterful teatre de carrer (street theatre) came to the UK courtesy of the London International Festival of Theatre (LIFT), who brought The Devils (Dimonis) to Battersea Park – a piece which somehow made it feel like there were hundreds of these mad devils popping up unexpectedly from the bushes, brandishing flares, and chasing us down the paths of this urban park. Although in style very different to La Fura, Els Comediants shared their multi-disciplinary approach, and their exuberant energy – staging work in unusual spaces and breaking down barriers between artist and audience. These things feel pretty usual these days, but in the 1980s it was far less common, and for many British artists, Catalonia was looked to as ‘market leaders’ in the development of outdoor and site-responsive performance, and for a cross-artform practice in which visual artists, actors, musicians and circus artists were all brought into the melting pot.

Another legendary Catalan artist presented by LIFT was Albert Vidal, who turned himself into an exhibit, taking up residence in London Zoo – audience members (and regular zoo visitors) getting to see him eat, sleep and field the deluge of chocolate biscuits offered through the bars of his cage by small children. Vidal’s work is still regularly cited as one of the most adventurous examples of site-responsive performance ever seen!

Els Comediants: Dimonis (The Devils)

These trailblazers have been followed, in more recent years, by a new generation of equally vital and extraordinary Catalan artists who are often difficult to pigeonhole, choosing to cross established boundaries of form and practice.

Take, for example, the work of Barcelona based Xavier Bobés, who brought Things Easily Forgotten to the London International Mime Festival on two separate occasions. The show, which plays to just five audience members at a time in a specially created installation space, feels like a cross between a seance, a family gathering, and a magic show, as the dead of twentieth-century Barcelona are conjured up for us through an extraordinary array of printed ephemera, everyday objects, and crackly sounds that come from a vinyl record player. Bobés holds the space beautifully – sometimes silently, sometimes drawing us in with text. It leaves you with the sort of bittersweet melancholy you feel when you find a cache of old photographs in your grandmother’s wardrobe. There is an added poignancy for anyone with an interest in the painful history of Spain and Catalonia over the past 100 years, particularly the Franco years.

Bobés is one of the Catalan artists programmed and supported by Spoffin, an annual street arts festival based in Amersfoort, in The Netherlands. The festival’s artistic director, Alfred Konijnenbelt, has some thoughts on why so many wonderful artists emerge from Catalonia:

‘They strongly believe in their own culture and are proud of it in a sincere and honest way. Catalonia invests a lot of time and money into the arts – for example, through Institut Ramon Llull. Every year, at festivals in Catalonia, I discover the most beautiful performances. Productions that are distinguished by a beautiful balance of emotion and mind. They are strong conceptually, with the ability to touch your heart.’

Asked to name a company that captures the zeitgeist of contemporary Catalan performance work, he picks Kamchàtka, who have often brought their work to UK festivals, most recently to Stockton International Riverside Festival (SIRF) in August 2019:

‘Kamchàtka is the Catalan company that is always ahead of the times’ he says. ‘As early as 2006, they focused on the subject of refugees, creating performances that are very touching and direct, while leaving plenty of space for your own imagination. They made me feel close, guilty, in love, loved, sad and super happy — sometimes even in one single hour. Kamchàtka has a direct connection to my heart.’

In 2017 Spoffin presented a Catalan and Balearic Islands focused programme, consisting of eight different shows of outstanding quality. Alfred picks another favourite artist, presented in that programme:

‘One of the most inspiring pieces was Públic Present 24 hores by Ada Vilaró, in which she performed non-stop for 24 hours at the same spot in the middle of a big square, in pure silence, claiming public space is for everyone, and contacting audience members just with her eyes. This was specifically touching because Catalonia had just faced a terroristic attack and had come under huge pressure from the national government of Spain’.

Ada Vilaró: Públic Present 24 hores, Spoffin festival 2017. Photo: Wim Lanser

This last comment ties in with a thought from Gebra Serra, co-ordinator of Trapezi, the biggest contemporary circus festival in Spain, which takes place every May in Reus (a city that is an hour away from Barcelona):

‘Performing arts, especially, street arts, have been a tool for political vindication at the start of our democracy, often used to occupy public space and to empower the public.’

Trapezi programme Catalan, Spanish and International work. They have moved on from being presenters to also being producers, and in 2019, they produced their third small-format show, Davaii, a two-person show by Domichovsky & Agranov; and also co-produced (with Fira Tàrrega, MAC Barcelona and other partners) a larger scale show called Dioptries, by Cia Toti Toronell.

Trapezi also collaborate with SeaChange Arts and Institut Ramon Llull in the process of selection for the Catalan companies who are invited to perform at Out There International Festival of Circus and Street Arts in Great Yarmouth. Gebra cites Gregarious, by Cie Soon (Manel Rosés and Nilas Kronlid), as a show that she is particularly pleased to have supported.

I see Gregarious at Out There, where it is presented on the main stage of St George’s Park, at the heart of the festival. Ostensibly a piece about sport, two male athletes sweat and puff as they run around the stage towards an imaginary marathon finish line, battle over a teeter-board, and work together to erect a Chinese pole. What it’s actually about is the relationship between the two. Colleagues, collaborators, rivals, brothers, lovers? They seem to be all of these, at various points in the piece, which is meticulously structured, every moment of its 45-minute length used expertly in the telling of its tale, and the exploration of said relationship. They push and pull in a novel take on hand-to-hand and acrobalance, bicker and barter in acrobatic dance-offs, carry each other in fireman lifts, kick-start their seemingly lifeless partner with a hefty catapult from the teeter-board, swing merrily around the pole in an easy rivalry, wrestle, and slow-dance… The skills are paramount and of the highest level as they interrogate the circus forms used without feeling the need to dissemble them. Parallel to the investigation of male relationship is a gentle commentary on cultural heritage. Catalan acrobat Manel Rosés carries on the pole to a strident Paso Doble, strutting like a matador; the smiling Swede Nilas Kronlid gives us crowd-pleasing gyrations to a Eurovision-friendly Swedish pop tune. It’s a complete delight, from beginning to end – and like many other great contemporary circus shows, the result of cross-European collaboration.

Cie Soon(Manel Rosés and Nilas Kronlid): Gregarious

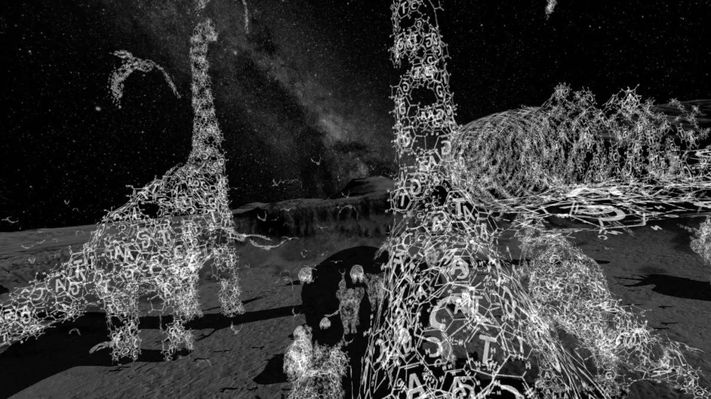

Also seen at Out There Festival is Collettivo Terzo Livello’s Documento, presented in the romantically named Dissenters Graveyard, a secret garden tucked behind a market. The aspect of this work that interests me most is the excellent interaction with the site. Boundary walls are climbed, walked along, and become a stage for juggling; benches and wheelie bins are used to clamber and trip over, or to climb into; old tyres are piled into towers, and become strange garments when stacked up over bendy bodies. This troupe of Italian and Catalan artists are supremely talented acrobats, although mostly they play down and deconstruct their circus skills with clever clowning as they trip and fall and flounder – morphing into dogs, battling over the inanimate objects they are giving life to. This is not the case in the (almost) finale of the piece – here, the pure skill and spectacle of circus is allowed full reign in a thrilling hair-hanging act, the performer emerging from a black bin liner filled with plastic and bubblewrap, like a strange new bird hatched in a nest of waste materials. She fashions herself a dress made from pieces of see-through blue plastic that look like disposable hospital gowns, attaches her hair-piece to the rope, and is hoisted high up into the trees, spinning furiously. It’s a great moment – an image of breathtaking beauty fashioned from an ugly mess.

Collettivo Terzo Livello: site-responsive circus experimenters

Collettivo Terzo Livello are one of many companies supported and nurtured by La Central del Circ, a research and creation centre for contemporary circus with a mission to provide resources for training, research, creation, production, and community building. Johnny Torres (artistic director) and Nini Gorzerino (project director) are its key movers and shakers, and they describe their organisation as ‘a contemporary circus lighthouse in the Mediterranean arc’.

Over the years they’ve given support to new collaborative circus formats or projects, ‘in order to propose other models of understanding and sharing circus arts’. So an experimental group like Collettivo Terzo Livello fit perfectly within their remit. Terzo Livello define themselves as: ‘A circus group whose works starts from artistic research, giving the artists a free space to explore and experiment on several issues, in spaces that inspire them.’ Johnny and Nini of La Central del Circ say: ‘Research is an essential element of the artistic processes… providing artists with time, space and economic resources to deepen in their practices gives them the opportunity to escape the pressure of success.’

Challenging ‘classist’ models of performance spaces led by market forces, they are particularly proud of a venture called ‘The week of rupture and transformation’ which began two years ago, the idea being to give, during one full week, the centre and all its economic resources to local artists, and to allow them to do whatever they want.

Joan Català: Pelat

Amongst a hefty list of artists that La Central del Circ admire and support is Joan Català, who British audiences may know for Pelat, presented as part of a Catalan programme at the Greenwich and Docklands Festival 2014; and Irish ones for his appearance at the 2019 Spraoi Festival in Waterford, Ireland, which this year programmed a number of Catalan and Balaeric artists.

Pelat, which uses audience participation as a key element, is, according to Joan Català, ‘an experiment which has become a spectacle’. He says that his goal is to remind people of the value of collective work – work that is ‘handmade, artisan work, not reliant on technology’. Part of the show involved audience members instructed to build towers, referencing the famous Castellers – although in this case it is with logs rather than human bodies. Talking of those legendary human towers, which I’ve had the pleasure of witnessing rise and fall with spectacular skill at Gràcia festival in Barcelona, I was delighted to learn recently that there is now a London branch of the Castellers!

Català is not the only artist from the region who employs and references local tradition and folklore, and Trapezi’s Gebra Serra reflects that one defining characteristic is a holistic integration of art and daily life:

‘We have a long tradition of popular cultural activity here: every village has a lot of cultural associations – it’s an ongoing activity of our society.’

This thought is reflected by Catalan theatre artist and teacher Marian Masoliver, co-founder of the internationally renowned Actors Space training centre, which is located just outside of the ancient Roman city of Vic (an hour or so north of Barcelona). Marian, who trained at Ecole Jacques Lecoq in Paris, and was subsequently a performer with La Fura dels Baus, now mostly dedicates herself to teaching and running the centre, which is attended by participants from all over the world. But she and her English partner Simon Edwards are also engaged with the local community, co-running a carnival organisation in the small Catalonian town of Mollet – an opportunity for community celebration, and to laugh together at the ridiculousness of human behaviour. Marian cites ‘tradition, colour, music, and spontaneity’ as key Catalan characteristics, describing the work as both celebratory and meaningful.

It is something that comes up again and again – this way of sitting between populism and experimentation. Legendary Catalan company Els Joglars have as their strapline ‘combining avant-garde and popular theatre’ and talk also of the need to ‘recreate the age-old inconstancy, anarchy and individualism’ of their homeland.

Gebra Serra of Trapezi again: ‘Catalan performing arts are different to Spanish performing arts because historically Catalan artists have looked more to the rest of Europe, and they have evolved faster.’

Cia Toti Toronell: Dioptries at Fira Tàrrega 2019

Catalonia has worked hard both to face outwards and to welcome the world in. It is no coincidence that one of Europe’s leading international performing arts market (with a special focus on outdoor arts and the public space) is held there – the Fira Tàrrega, which since 1981 has taken place every September in Tàrrega, in the province of Lleida.

Fira Tàrrega describe themselves as ‘a shop window for creativity’ and their mission is ‘to invigorate the performing arts market, the internationalisation of the creators, and [to support] the generation of strategic alliances to develop international street art productions or circuits’. The 2019 edition opened with a talk entitled ‘Public Space: Social Transformation, Existence, Creation’ – which they feel was an unusual but successful opening gambit. So, a parallel here with Out Theatre Festival 2019, who dedicated their professional programme Rise Up! to the role of outdoor arts in cultural democracy. These are most definitely topics of great relevance in these tumultuous times – and a reminder that the origins of street theatre are inextricably linked with protest, social engagement, and political action.

Anna Giribet i Argilès, artistic director of Fira Tàrrega says ‘We think that Catalan artists are very good at small- or medium-scale street arts and installation work. They are particularly good at telling local stories that are of interest at the global level. There is a concept that encompasses that: glocal!’

Dulce Duca: Sweet Drama

But what of the artists themselves? What do they think? Juggler and physical theatre performer Dulce Duca, programmed in Out There Festival 2019 with her new show Sweet Drama, is well placed to answer:

‘I think that Catalonia has become an international artistic meeting point where many cultures cross. It’s a very rich environment with this mix of artists from all over the world. They are open to receiving new artists and to supporting them. I came from Portugal, I lived in France for five years, and then in Catalonia for the last nine years, where I’ve felt really included. I have to say that Institut Ramon Llull have supported a lot of artists to develop their work and to tour internationally – and that has helped the world to get to know Catalan artists…’

Dulce’s first major international show, Um Belo Dia, was presented at a previous edition of Out There. Her second solo, Sweet Drama, has been developed in collaboration with SeaChange Arts’ artistic director Joe Mackintosh, and premiered at Out There 2019.

It starts with a mock no-show as the stage manager announces that Dulce is late. The phone rings – mobiles become a motif of the piece – and we learn that she’s on her way. And here she is – running around the corner in a gold dress, red tights, and strappy high-heeled gold sandals. We learn that she’s dashed away from her friend’s wedding reception to do this show. There’s a storyline about a missing present – a commissioned painting that hasn’t been paid for, which eventually resolves in a live painting scene – but the piece is less about story than character. Dulce is a great clown, and in this piece she has created a comic character that is simultaneously deplorable and lovable. Like all good physical comedy performers, she mixes technical skill and clowning to great effect. Her core skill is juggling, and she finds ingenious ways to explore the comic possibilities of a set of clubs and a pair of half-on half-off tights. The high-heeled shoes come off, and on go – a pair of high-heeled roller-boots! The piece is a collaboration with local skateboarders who are well-integrated into the piece, and Dulce is a generous performer, letting them showcase their skills.

Dulce is particularly pleased with this aspect of the piece:

‘I am especially proud of what I am doing with the skateboarders. In my opinion they are jugglers – they manipulate skateboards with their feet. They have a very similar dedication. I want to be a catalyst, so the audience can see the greatness of what they do. I’ve been studying them and working with them to understand how can we fit together, and what can we share and evolve. It’s a very rewarding experience.’

Pau Palaus: Petjades

Just round the corner from Dulce’s Great Yarmouth skatepark is the idiosyncratic King Street, which runs parallel to the waterfront – an interesting mix of secondhand furniture shops, grocery stores, pubs and cafes. Yarmouth has a large immigrant population, with Polish and Portuguese speaking communities (from both Portugal and Angola) particularly in evidence in the groups of people sitting outside the shops and cafes. Into this environment come two men, and a cello. The cello is mounted on a trolley, and a gently melancholy tune is being played by a man in a brown wool coat and floppy felt hat. A younger (or perhaps he’s just more child-like) man in a teal-coloured coat and flat cap is pushing the trolley along. This is Catalan company Pau Palaus, and their promenade show Petjades is a beautiful and moving piece of work about migration – evoking both historical experience (the piece was inspired by Second World War stories) and the current so-called ‘refuge crisis’. How much has actually changed, we wonder? The narrative is simple, but everything in this word-free piece is executed with precision, and the interactions with the audience are handled with the expertise of experienced performers.

The fifth show in Out There’s Catalan programme is PakiPaya’s TocaToc, a two-person circus-theatre show (set in their own big yellow tent) which explores romantic relationships between men and women. ‘Two people meet, they say hello, they hug, they say goodbye, they leave…’ says the voiceover, and the words are acted out in numerous physical motifs – mimed, clowned, then abstracted into dance, and used as the catalyst for a number of skilled aerial doubles act on a specially-designed cradle structure. At first, the doubles acts are comic, with slaps and kicks and comic drops onto a mattress. The final one is tender, loving and totally beautiful. Before we get to that point, we work through very many comic scenes that exploit and celebrate popular culture, with our two performers dashing through a whole wardrobe of costumes, and exploiting the potential of their specially designed space – a unit with two doors is run around, stood on, and popped in out of with excellent comic timing and clown sensibility, and the aerial truss/cradle and ropes are used with expert ease.

Cia Paki Paya: Toca Toc

As with other European festivals, such as Spoffin or Spraoi, the relationship between Out There and Catalan companies is one that has been developed over a number of years. This special relationship has been brokered by the ‘Catalan culture abroad’ organisation, Institut Ramon Llull, working with Trapezi festival. Amongst other forms of support, the Institut has an Artists’ Mobility grants programme that gives support to Catalan artists to present or tour performing arts work. Four of the five companies seen at this year’s Out There festival were supported by residencies in Great Yarmouth, before presenting their work in the festival.

It is clear from the work seen not only at Out There festival 2019, but also at other festivals and events across Europe, that Catalonia remains a fertile bed of excellence and experimentation, producing high quality and innovative performing arts work, and continuing to both honour its own traditions and to look outwards to the wider art world.

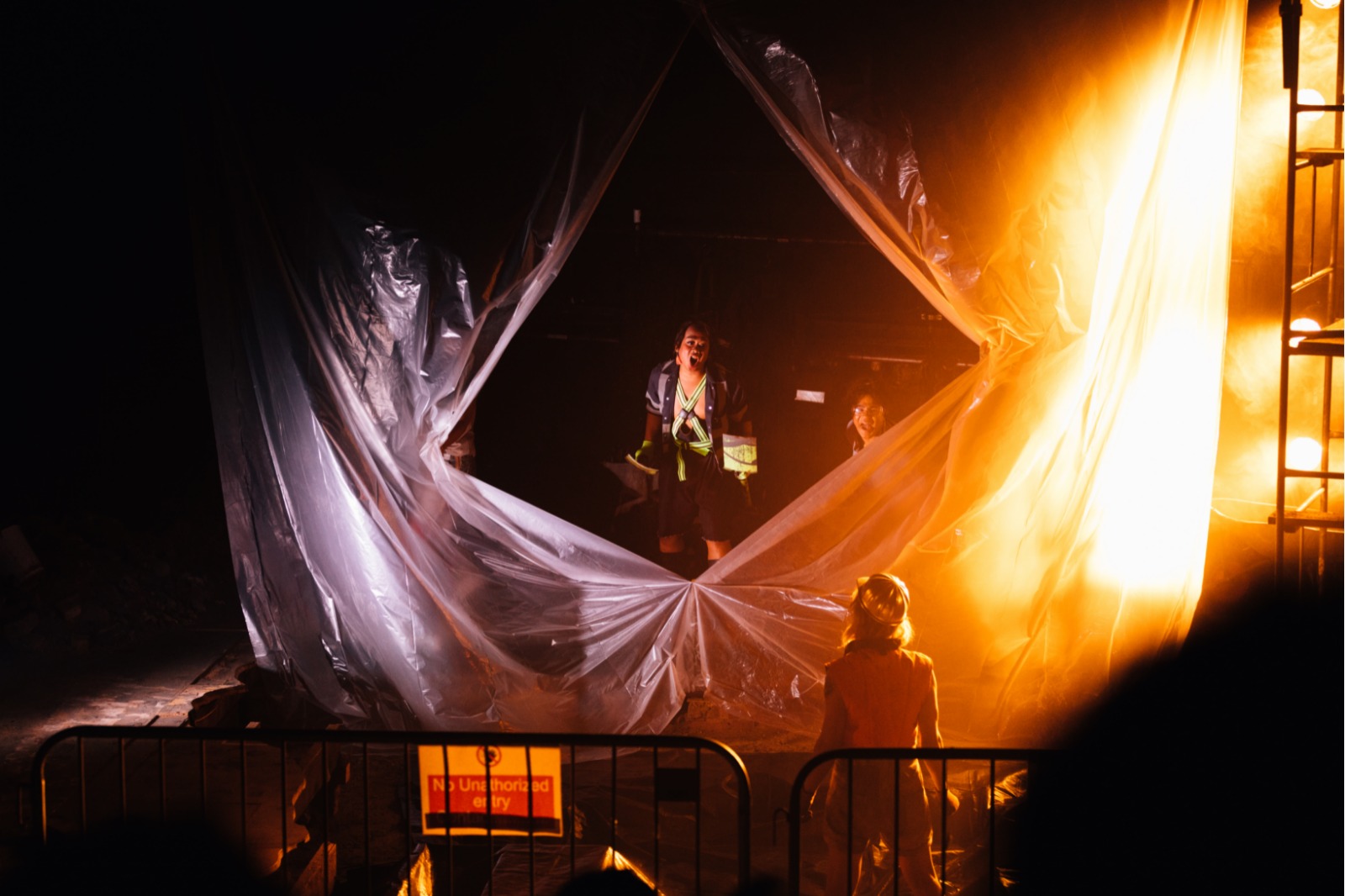

Featured image (top of page) Catalan street theatre company Kamchàtka

This article is published by Total Theatre Magazine in collaboration with Institut Ramon Llull

Institut Ramon Llull is a public body founded with the purpose of promoting Catalan language studies at universities abroad, the translation of literature and thought written in Catalan, and Catalan cultural production in theatre, film, circus, dance, music, the visual arts, design and architecture. For more information see https://www.llull.cat/english/home/index.cfm

Out There International Festival of Circus and Street Arts in Great Yarmouth is produced by SeaChange Arts which is headed by artistic director Joe MacIntosh and executive director Veronica Stephens. https://seachangearts.org.uk/

The Out There 2019 programme took place 13–15 September, and included five Catalan companies:

Collettivo Terzo Livello, Documento; Dulce Duca, Sweet Drama; Pau Palaus, Petjades; Cia PakiPaya, Toca Toc; and Cie Soon (Manel Rosés and Nilas Kronlid), Gregarious.

www.outtherefestival.com

Trapezi is a circus fair focusing on Catalan productions, as well as international shows. This year it celebrated its 23rd edition. It is held in May in Reus, a city in the province of Tarragona. https://www.trapezi.cat/en/

Fira Tàrrega is an international performing arts market with a special focus on outdoor arts and the public space. It is held every year in September in Tàrrega, in the province of Lleida. https://www.firatarrega.cat/en_index/

Spraoi International Street Arts Festival takes place in Waterford, Ireland, every August: http://www.spraoi.com/

Spoffin Festival, is held in August in Amersfoort, The Netherlands. It celebrated its tenth year in 2019: https://spoffin.eu/

La Central del Circ, based at the Parc del Fòrum in Barcelona, is a creation centre which also makes its resources available to circus professionals for training, practice, and continuing education: https://www.lacentraldelcirc.cat/

The Actors Space is an international training centre for theatre and film, located in a place of outstanding natural beauty near Vic, one hour from Barcelona. https://www.actors-space.org/

La Fura dels Baus was founded in 1979 in Moià, Barcelona. The company are known for their pioneering urban theatre, use of unusual settings, and blurring of the boundaries between audience and performers: https://www.lafura.com/

Els Comediants is a collective of artists, actors and musicians who create collaborative work. The company was founded in 1971, and its base is in Canet de Mar (near Barcelona): http://comediants.com

Castellers of Catalonia