Dorothy Max Prior sees vessel, the new production by Total Theatre Award winner Sue MacLaine, and talks to the writer about the personal and the political, about power and privilege – and about whose voices get heard and whose silenced

Let’s talk about what defines my reality

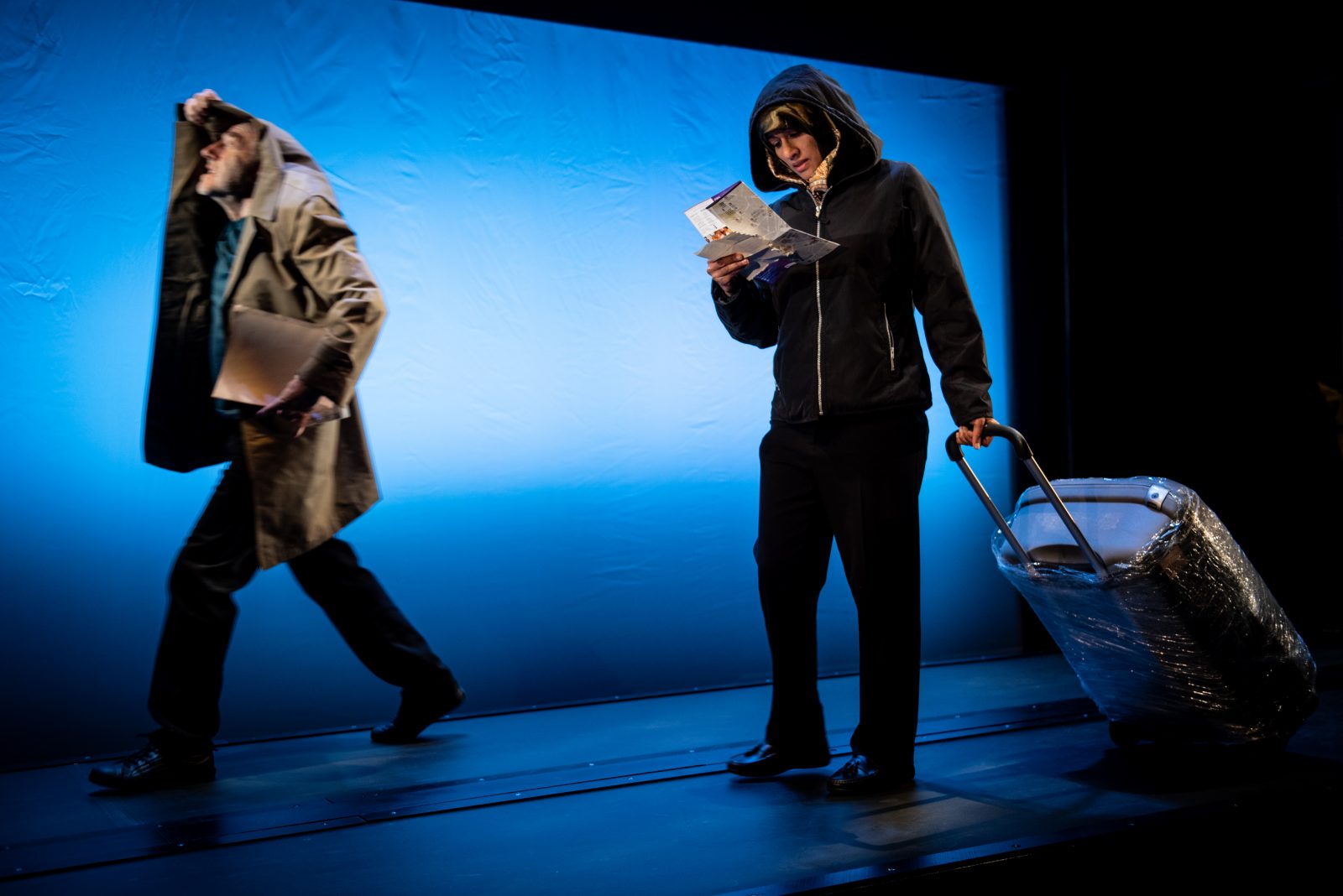

Four women, each sat on a chair, each chair inside a circle. Circles that have morphed from squares, delineating their personal space. They are alone, but together. The floor and the wall behind them are a rich rusty orange. Their attire is simple but not overly frugal; plain-coloured dresses in a luscious palate of blue-greens. Turquoise, leaf green, peacock blue, cyan. Jewel colours. Tapestry colours. It makes for a pretty picture. Birkenstock-style felt shoes on their feet. A metal water bottle by each chair. A book in each lap. They sit in silence, watching us watching them, looking out and smiling gently. There’s a low-key drone and murmur of voices in the background, as if coming from elsewhere, the sound only just at an audible level. A veil has been drawn back. The invisible made visible. We are allowed in.

We are in the world of vessel, the latest production by Sue MacLaine.

Read. Pray. Sew. Counsel.

The inspiration for vessel is the medieval practice of Anchoritism, which saw women choosing a life of confinement within a locked cell housed within a church. Once admitted to the cell, the women were dead to the world, and thus were often given funeral rites as they entered. In some cases, they dug their own graves within the cell, scraping the earth with bare hands. But they were not imprisoned for a life of mortification; they were there through choice, for a life of contemplation. Much of the day would have been spent in silent prayer, but there was contact with the outside world via a small window or ‘squint’ allowing for those outside to consult with, and take advice from, the Anchorite, who was seen to be closer to God through her choice of abstention from the hustle and bustle of the world.

What might the modern equivalent be? A life without Twitter and Facebook and Gmail and mobile phones, perhaps? A life in which personal space was valued, cherished? In which listening to others, rather than being heard – forcing through ‘your truth’ – was seen to be of paramount importance?

While the world spins out of control outside, take refuge. Women only spaces. Political separatism so that people can find their voice. Withdraw in order to look after and heal yourself. But don’t withdraw to hide, to pull the covers over your head and hope it all goes away. Withdraw in order to understand better, to re-arm, to learn to be a better ally.

These are some of the musings that have informed Sue MacLaine’s powerful new piece. It is a work that is determinedly not autobiographical. It is about us all. It is about speaking out about violence and oppression. It is about fostering a new inclusivity in politics and in everyday life. It is about emotional literacy. It is about understanding that the personal and the political are always in dialogue.

Let’s talk about the view from where you are sitting and the view from where I am

The women speak. Individually, at first, solo voices; then overlapping, in cannon, in chorus, in rounds. The words are important for their semantic meaning, but there is also the semiotic qualities of the sounds; the rhyme and rhythm, alliteration and repetition. They speak, they listen to each other speak. They face front to speak, they turn their heads towards each other to listen. Chairs are sometimes angled in. Sometimes there are gestural responses to another woman’s words. As the words flow out from mouths as sound, they also flow in visual form across the orange backdrop as projections – creative captioning giving us clear, concise rows of white text placed above a talking head; or forming arrow-heads shooting out at us as a multitude of voices overlap; or arranging themselves into a Merz-like concrete poem breaking a silence.

Ideas around personal space, public space, political space, patriarchy, prostitution, power, and privilege are played out. Oh, and while we’re at it, who does the washing up? The public and the private. Who’s to say what is more important, the big issues or the supposedly little things? The domestic narratives. The spotlight is on agency, privilege and representation. Who gets to speak? Who gets listened to?

Writer and director Sue MacLaine, talking to me after the first previews of the show at the Attenborough Centre for Creative Arts, cites the inspiration of the writings of Judith Butler, and in particular her collection of essays entitled Precarious Life: Who has value and who doesn’t? Why does our focus go here and not here? Whose life is worth anything? Princess Diana is killed and the world weeps. But what about the 800 dead babies and children found in graves in the grounds of a home for unmarried mothers in Tuam, Ireland? Who weeps for them?

Who’s life is grieve-able?

Let’s talk about mass-mediated tragedy. Let’s talk about that

Let’s talk about taking a stand, taking the stand

Vessel is performed by a diverse cast of four women – Karlina Grace-Paseda, Tess Agus, Angela Clerkin and Kailing Fu. Sue MacLaine, writer and director is not amongst them; has chosen not to be in this show. ‘I can do my job better from outside,’ she says. The performers are also credited as collaborators. ‘We arrived on day one of rehearsal with all of the text and more’ says Sue. Quoting the legendary comedian Les Dawson (‘I can play all the right notes but not necessarily in the right order’) she speaks of the intensive process in those early weeks of workshopping the text with the actors. In the original script, no lines were assigned. The painstaking process started of working out not only who would say what, and when, but how all the voices and physical actions would be choreographed into one harmonious whole. Not, says Sue, that everyone needed to have exactly the same number of words to speak – but she wanted ‘everyone present and engaged at all times – speaking or in silence or in movement’.

She came in with a new version of the script almost daily in those first two weeks: ‘They were incredibly generous…’ she says of her actors, adding that she really enjoyed that process of asking ‘what do you think?’ – adding, I knew what I thought, but I wanted to know what they thought.’ These conversations inspired the subsequent revised script. Whole sections of text were cut. Luckily, Sue enjoys the editing and revising process: ’I like cutting things as much as I like writing them.’ She quotes Cindy Oswin quoting Ken Campbell when she worked with him in the original production of The Warp. ‘Say it or cut it’ said Ken. Sometimes a line might be good, but the rhythm of the line is ‘not helpful to the actors’. If words or phrases are tripped over when read aloud, it’s a sign they need to go elsewhere or be cut – ‘cutting through choking’ you could say.

Let’s talk about taking more than your fair share

Who gets to speak, and who gets listened to, is a recurring theme in the text of vessel, and an ongoing preoccupation of Sue MacLaine’s research. ’Do I have to be everywhere and visible?’ she ponders, ’Might it be better to keep my gob shut? Don’t disrupt the discourse!’ Repeatedly, Sue mentions her desire to be a good ally, and this being key to current forward-thinking politics. Whose revolution is it? Who have we excluded from the table? One person’s liberation can be another person’s oppression… Those of us with privilege need to look to what is being asked of us, rather than rush through the door with our own solutions. She quotes as an example the right of Deaf people to have Deaf-only spaces where they don’t have to negotiate the hearing person’s desire to communicate. LGBTQ+ people need safe spaces where they can operate without having to explain themselves, away from the gaze of those who see them as ‘other’.

As a BSL interpreter and longterm ally to Deaf people, Sue was keen to find a way for every performance of the show to work for people with or without hearing. The show thus uses creative captioning throughout, designed by digital artist Giles Thacker, which works harmoniously with the lighting and set design by Ben Pacey, creating a complete and interweaved scenography.

Inclusivity, genuine inclusivity not tokenism, is of paramount importance to Sue in the making of her work. In the casting calls for the show, it was stressed that the company were looking to put together as diverse (in every sense of the word) a group of women as possible. The cast chosen ranged widely in age and ethnic heritage, and included people with and without physical disabilities.

‘What is my “in” to empathy?’ asks Sue. ‘My “in” to action; to becoming an ally?’ Sue talks of ‘not becoming enamoured by our own oppression’ and whilst respecting the individual needs of us all, looking beyond the purely personal to a political perspective that gives more space to neglected voices. When weighing up the pros and cons of rival rights, Sue’s go-to question is, ‘Does this do harm?’

Let’s talk about knowing when to leave and knowing that you can leave

Vessel is a piece of many words, but soundscape and choreographed physical action are also crucial to the dramaturgy of the piece. The sound design is by Owen Crouch, who has built a complex multi-layered world of sound that ebbs and flows throughout the piece. Sometimes it is so low it’s hardly there – a kind of hum or murmur in the background, as if heard through three-foot-deep stone walls. At other times, the sound rises to occupy the space, most noticeably in the word-free choreographed section that ends the show. Sue talks of her desire to have a Butoh-esque relationship between sound and physical action, in which the two operated in tandem rather than one illustrating, or providing the impetus for, the other. Terry Riley is also cited as an influence on the sound design.

Owen, together with designer Ben, and projections artist Giles, were involved from the early days of the project. Choreographer Seke Chimutengwende was the last of the creative team to join, the introduction coming via project dramaturg Jonathan Burrowes. Sue speaks of her admiration for his generosity of spirit. ‘He and I have a similar aesthetic’ she says, ‘He is a less-is-more man, who likes to take his time.’

At the point at which Seke joined, Sue had a pretty clear idea of the structure of the piece, and what she wanted from a choreographer. She knew, for example, that having delivered a barrage of words to the audience for most of duration of the piece, she wanted it to end with a movement section. Although there is a choreographic sensibility throughout the piece – every opening of a book, every turn in a chair, or turn of a head, is carefully planned – it is this final 8-10 minutes of vessel in which Seke’s work comes to the fore.

Seke’s choreography for this section was informed by the gestures created by the women in rehearsal – movement motifs that needed to work for everybody. Every body. Here and elsewhere in the piece, gestural movements derived from sign language feature, Sue saying ‘I wanted to create an etymology from within sign language’. The sign for imagination features strongly. This, says Sue, because of ‘the power of the imagination to transform’. At one point there were over 700 Anchorite cells, and, she says, ‘although the Anchorites follow their practice in isolation, they are joined together in an imaginary community.’ She is also interested in the role of imagination to make the cell not a cell, but a site of spiritual growth.

Other sign-language informed gestures derive from signs related to history, and signs for delineating time. She demonstrates one of these, calling it ‘the Back to the Future sign – the past coming into the present, the present going back into the past’. Another denotes a moveable timeline, expressing the carving up of time.

The final few minutes of the show give us a powerful blend of dramatic gestural movement and intensive waves of sound; the accumulated power of the words we’ve heard washing over us for the past 45 minutes still ringing in our ears.

Four women, four unique individuals, in their own space yet also in a shared space. Each engaged in a spiritual struggle ‘on behalf of herself and the wider world’. Their radiance shines out.

Photos by Hugo Glendinning.

Vessel is currently (autumn/winter 2018) touring the UK, dates below.

The Attenborough Centre, Brighton (preview) 25 & 26 October, 2018

Battersea Arts Centre, London 6–24 November, 2018

DaDaFest, Liverpool, 3 & 4 December, 2018

For more information about the company, including further dates for vessel in 2019 to be announced, see www.suemaclaine.com