Summerhall are all-victorious in the Innovation, Experimentation and Playing with Form category of the Total Theatre Awards 2017

There is an irony, says Rachel Mars, picking up her Total Theatre Award, in making a show about competition and envy that goes on to win an award…

Her show, Our Carnal Hearts, is a total delight. The ‘thou shalt not covet’ commandment is investigated thoroughly: everything from the relatively harmless #humblebrag (let’s all sing a long to the Humble Waltz!) to the deeper, darker nastier parts of our psyche that wishes ill upon our dear friends and family when they are perceived to be doing better than us. This isn’t just a theoretical musing: Rachel bears her heart, revealing her own ‘spiky, sticky, shameful bits’ – including her hatred of her pretty blonde cousin with the angelic singing voice and her envy of artist friends who win cushy awards or commissions. The audience are implicated too: we are asked to picture a moment when we heard some good news about someone close to us, and wished them ill. We are then asked to share, which most refuse to – but a brave young man sitting next to me offers up his envy of his sister, who quits a challenging job in order to pursue a spiritual path. We are all asked to join in with him in shouting our congratulations.

Two narrative motifs weave through and eventually merge: the old Yiddish joke about a fairy who offers to grant a wish, but with the proviso that whatever you wish for, your neighbour gets double (it doesn’t end well); and the story of a high street plot that morphs from community park to car valeting shop to upmarket jewellers to nespresso boutique… Oh envy, thy twin sister’s name is aspiration. The text is marvellous – wise and witty and deliciously wicked – we wouldn’t expect anything less from Rachel Mars. But what pushes this show up from great show to award-winner is the eloquent way that the in-the-round staging, spoken word, and live music (composed by Sh!t Theatre’s Louise Mothersole) interweave. The piece is set to resemble a church service, with a choir of singers placed within the audience, and sermon mics on stands placed in each of the four aisles. The central space is used for ritualistic actions in this unusual service – these including the laying out of a geometric pattern of coffee grounds (Aleister Crowley eat your heart out) and the beating out of sins with a couple of rubber chickens. Hallelujah! We are saved!

Our Carnal Hearts was presented at Summerhall, and I saw it immediately after seeing what was to become another Total Theatre Award winner, Palmyra, which is also, in a very different way, an investigation of the sinful side of human behaviour. In this case, Thou Shalt Not Kill (not bully, nor beat, nor terrorise) is the commandment up for investigation.

The show is made and performed by Bertrand Lesca and Nasi Voutsas, who we could see as a next-generation Ridiculusmus (similarly a two-man outfit combining intense physical performance, spiky spoken text, and darkly comic clowning). Palmyra takes no prisoners. The scenography and choreography are totally intertwined, and there is a fantastic build of energy as our two protagonists spar and bully their way through an intense hour of crockery smashing, hammer wielding, and whizzing around on 4WD skateboards, in an exploration of ‘revenge, the politics of destruction and what we consider to be barbarian’. The audience are not allowed to remain neutral, and are coerced into taking sides: take the hammer, hide the hammer, give the hammer to him… Let’s call the whole thing off!

Palmyra provoked an interesting discussion at the judging meeting about who owns stories and who has the right to tell them, with some feeling that Syrians and those living close to ISIS-held territories might perhaps have a very different response to this show, which takes the destruction of the ancient site of Palmyra and its use as an execution arena as its starting point. There is also the question of whether, without the title and programme notes, the audience would even get the connection. But it won out in the end because the majority view was that this is a dramaturgically complete, beautifully structured and brilliantly performed piece of theatre. My own view? Humour and satire are vital tools in the fight against violence and terrorism. And the message of Palmyra is a sound one: Let him without sin cast the first stone – we all have the capability for violence within us, it’s how we handle it that counts. This is a show I had some reservations about when viewing but which has stayed with me, provoking new thoughts and responses long after the last piece of crockery has fallen. And ‘What’s happened here, then?’ could qualify as the best opening line of the 2017 Fringe.

Both of the above won Total Theatre Awards in the Innovation, Experimentation and Playing with Form category. There was a third winner here too: Selina Thompson’s salt. Which also involves things getting smashed – but this time it is an enormous block of Himalayan rock salt.

salt. is an autobiographical piece – but that tag doesn’t do it full justice. It is a piece that weaves together stories from a personal journey (a literal journey at sea and a metaphorical journey into the self) with an investigation into the legacy of colonialism and the African slave trade, via a journey tracing the route of the Transatlantic Slave Triangle that joins Britain, Ghana and Jamaica. Selina’s story of her sea journey, a quest to sit inside the history of the people – Selina’s ancestors – ends up being extraordinarily difficult, but provides an extra dramatic element to the artwork, in that something that could have been dismissed as a reflection on a long-gone past takes on a contemporary immediacy due to the artist’s appalling experiences of still-with-us racism. In an article Selina Thompson wrote for Total Theatre Magazine last year, in the early days of making the piece, she had this to say, by way of introduction:

‘On 12 February, I got on a cargo ship, and sailed from Antwerp in Belgium, to Tema in Ghana. I left there, and flew to Kingston in Jamaica, before sailing back to Antwerp via North Carolina. I returned on 12 April…

While I was away, myself and my film-maker had to split up, my grandmother died, my biological sister got in touch. While I was away, my hair was searched in customs, I tore the cartilage in my left knee, I listened to people stand outside my door and comment on the fact that I was “already as black as one of the niggers”. While I was away I showered outside while hummingbirds flew above my head, a French bulldog burst into my room and stole my luggage tags, and a load of flying fish jumped too high and landed on the ship I was sailing in.’

The show (which I saw in preview at the Attenborough Centre in Brighton) is a revelation. Selina Thompson, in her ‘act of remembrance and grief’ demonstrates a phenomenal ability to combine sharp writing with a winning personable delivery that breaks the fourth wall: embodied in the fact that we need to wear goggles when the salt rock is smashed; we are most definitely here together in this shared space.

In one of the most harrowing moments in the piece we stand with Selina before the Gate of No Return at the former trading fort Elmina Castle, Ghana, facing the Atlantic ocean and seeing with her the thousands of men, women and children forcibly removed from their homeland to work and die in the New World plantations. These moments of gravity are counterbalanced with gently humorous accounts of her telephone conversations to her Dad back in Birmingham, who takes some of the stories of the journey with – well, I’ll not resist the obvious and say with a pinch of salt.

Beyond the strength of the script, the scenography of the piece (with design by Katherina Radeva) provides a staging that is perfect for the story. A neon sign, a few plants, a simple and elegant white dress – it doesn’t take much, but it is all more than enough, a deceptively simple and elegant design. The enormous rock of salt is centrepiece, broken up with a pick-axe as the show progresses,the larger chips off the block to be laid out in representation of the people populating the story. We are one, it says to me – one race, the human race, united in our mineral essence, drops in the ocean.

All three of these winning shows are by young artists, and all were presented at Summerhall – which perhaps merits some comment.

Summerhall continues to be the venue that is the most likely to host the more experimental work being made, with the door always open for innovative international theatre. They do not shy away from the phrase ‘avant garde European theatre’ in their programme notes. The ever-enterprising Big in Belgium programme can be found there (Ontroerend Goed’s Lies making it on the the Awards shortlist), and the Northern Stage programme of new writing (which include Selena Thompson in its line-up) is to be found there, as it has been for a number of years. The future is taken care of in the form of a four-year residence at Summerhall for Rose Bruford College of Theatre and Performance.

This year, Summerhall also hosted the CanadaHub programme in its sister venue the King’s Hall, which included the brilliant Mouthpiece (reviewed here) and a very lovely piece of music-theatre featuring multi-instrumentalist Ben Caplan – Old Stock: A Refugee Love Story.

The 2017 programme also featured many companies dear to the hearts of Total Theatre Magazine’s editorial team – including many previous Total Theatre Award winners or shortlisters: Ridiculusmus, Sh!t Theatre, FK Alexander, Dancing Brick, Richard Gadd, Action Hero, RashDash, Orkestra del Sol, and Julia Croft (whose Power Ballad was shortlisted for the Total Theatre Emerging Artist Award 2017). Which is quite a list – and only a fraction of the shows on offer.

On the day that the Fringe closes, I sit at home, well away from Edinburgh, with my Summerhall programme and I grieve for all the shows I didn’t get to see there in the brief two weeks I spent in the Burgh during August 2017. Never mind, there’s always next year…

Summerhall is a year-round venue and gallery, housed in the former Royal (Dick) Veterinary College in Edinburgh. www.summerhall.co.uk

Selina Thompson’s salt. was seen in preview at the Attenborough Centre for Creative Arts (ACCA) at University of Sussex. www.attenboroughcentre.com

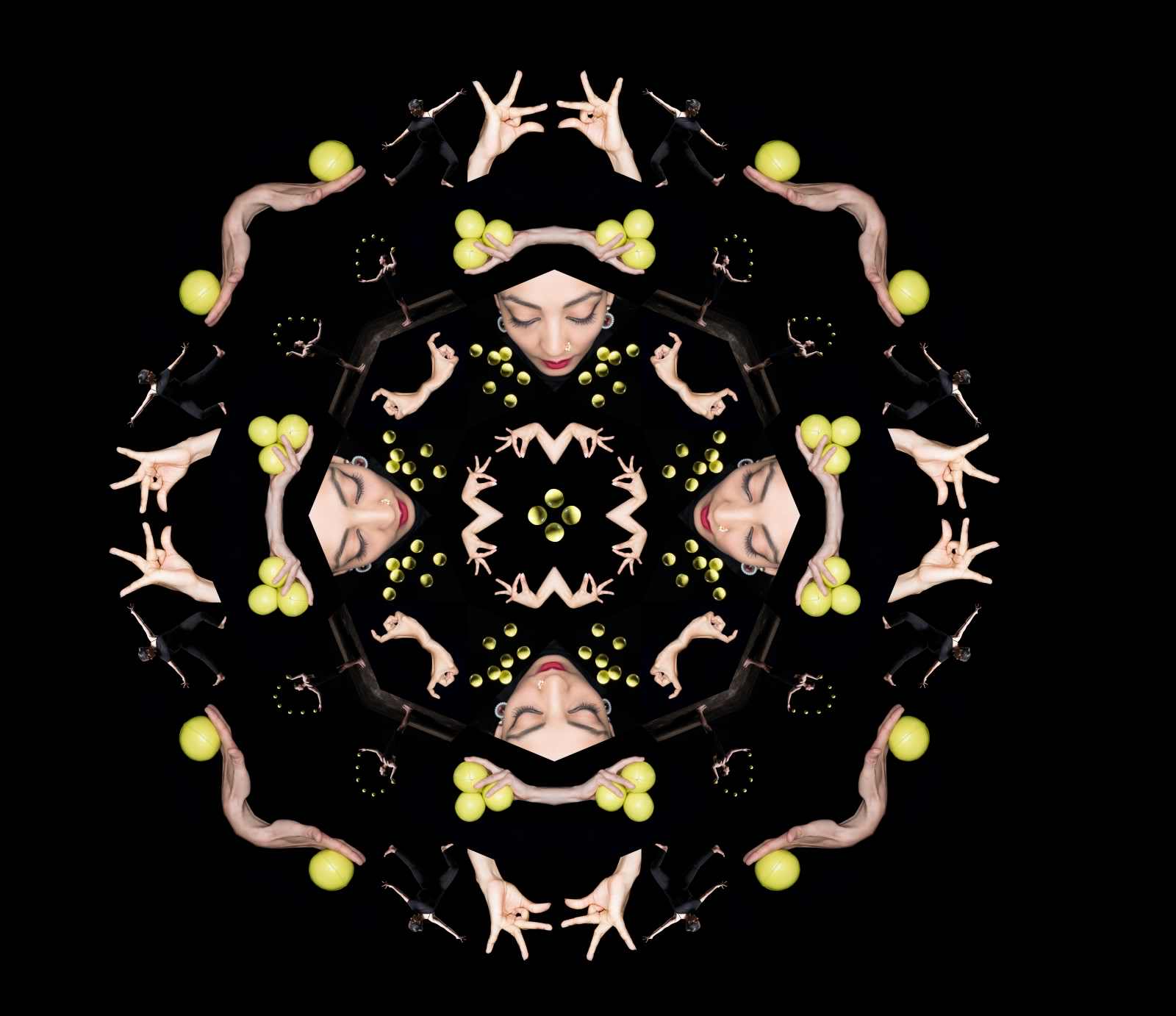

Featured image (top) is Selina Thompson: salt.