A plain and unadorned space, a circle drawn on the ground, a light, a chair. And a body. A human body. A bag of bones.

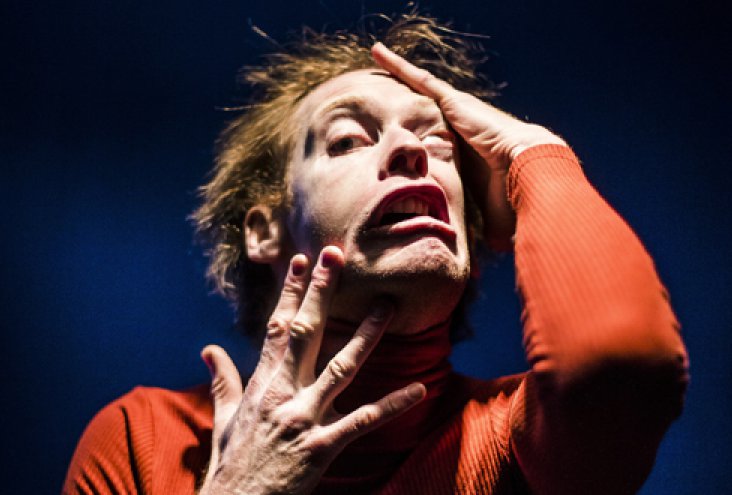

The body belongs to Thomas Monkton, seen previously at the Edinburgh Fringe and the London International Mime Festival with The Pianist. But Only Bones is a very different kettle of fish. Where The Pianist gives us stage full of kit and sees the performer explore a clownish relationship to objects – a grand piano, curtains, chandeliers, sheet music – Only Bones strips almost all else away and objectifies the body, Monkton reducing himself to modelling material. Except of course he’s not – with every clever trick, every brilliantly executed physical vignette, we are simultaneously enjoying seeing the body and its parts twisted and turned into all sorts of things, whilst yet appreciating the (super) human effort behind it. Ultimately, it’s a show about the human body, and being human.

So, what happens? We start off with socks, seemingly three socks on three feet, perched on the chair seat. But it is not three feet, it is two feet and a socked hand, in a kind of stand-off. Enter the other hand, bare, and things get even more bizarre. Now we have two hands like scuttling spiders. And a hand that tortures the other hand with red nail varnish. Now we seem to be looking at the back view of a headless man, his (jazz) hands enjoying a dance above his non-head, illuminated by an electric blue light.

Ah yes, the light! The bulb in the lamp above the performer’s head – or non-head – changes colour with each small scene. A deep maroon for underwater swimming (jellyfish or human!), for example. At first a straightforward change of state for each vignette, but then Monkton starts to subvert and play with this, getting rid of the deep water tank he can’t escape from by changing the bulb colour… There is also a lovely point at which the lampshade becomes a head, and a baby Anglepoise is cuddled – a perfect puppetry moment.

In many ways, the show is puppetry. No puppetry of the penis (thank the lord) but puppetry of the head, face, hands, arms, feet, legs, spine… This man’s ability to contort and manipulate his body is breathtaking.

There’s sound too – onomatopoeic moos and baaas in a silly (and very lovely) scene in which animals combine to form new hybrids, with some help from the audience. This moves into a kind of reverse beat-boxing or body percussion, in which sounds from inside have a forceful effect on the body. Eventually, all is resolved and here we are, looking at man, just a man, who is looking back at us.

Only Bones is a delightful show delivered by a highly skilled performer (who certainly knows his way around his own body) investigating the place where the circus arts of clowning and contortion meet puppetry and object theatre. Bravo, that man!