Body, blood, soul and divinity: Dorothy Max Prior takes part in a week-long exploration of secular ecstatic art, led by Nwando Ebizie and Jonathan Grieve of MAS Productions

Ancient gods have multiple purposes – they are complex, often contradictory, beings. Take, for example, Artemis. Goddess of hunting, but protector of wild animals. A virgin goddess who is nevertheless the patron of midwives and childbirth. So to create modern deities, let us look to the possibilities of creating flawed, ironic, contradictory creatures, at odds with the idealised monotheist God of the Christian religion.

It’s day two of our week together, and today we are creating contemporary gods and goddesses, using each other as modelling clay. Just as the Golem becomes a reflection of the needs, desires and anxieties of the person conjuring it from clay, and a portrait painted by an artist is always in some ways a self-portrait, so the deities we create become as much about us as about the person we are using as our model, even though this raw material, this person in front of us, comes complete with his or her gender, ethnicity, age, body shape, markings, piercings, hairdressings, and whatever else. We note the similarities and the differences between them and us. We are the same, yet we are different. We delight in the similarities and in the differences.

When we finish our modelling work, we look around at what’s in the room. Some images are clearly defined and labelled: for example, the Goddess of Contemporary Childhood is a girl in a short skirt, dishevelled hair, and messed-up make-up passed out on the ground, clutching a bottle – a good, straightforward commentary on modern life. Others are more complex, harder to pin down. The ethnicity of the model is often exploited, played with: a dark-skinned woman, cloaked and crowned, cuddles a black baby doll in one hand and a gun in the other whilst holding a scroll bearing a proclamation – a complex Mama Africa figure offering simultaneously the options of liberation through the power of the word, through nurturing of the young, and through violent political action.

We’ve arrived at these living statues through a process that has started with the Pocha Nostra exercise of ‘reverse anthropology’, developed by the legendary explorer of ritual, and exploiter of cliches of ethnicity and gender, Guillermo Gomez Pena. In this exercise, which can be challenging the first time you do it, one person is ‘scientist’ and one ‘specimen’. A process of exploration of the subject’s body leads to the ‘scientist’ carefully and respectfully looking, listening to, smelling, and touching the ‘specimen’. Over the week, we return many times to this exercise in different partnerships, each time building on it, so that the first stage of observation leads to manipulation, modelling, and re-styling the body in hand.

It is one of a number of Pocha Nostra techniques used throughout the week. Jonathan Grieve (co-facilitator of the week, with Nwando Ebizie) first encountered Guillermo Gomez-Pena at a lecture and performance at The Tate in 2003, later attending a workshop and performance with him at the Centre for Performance Research that summer. ‘His work was following similar lines to those we were pursuing in Para Active [the company he co-directed with Persis Jade Maravala] regarding social and cultural representation,’ he says. ‘Guillermo’s irreverent attitude brought out the anarchic side of my personality, which up to that point had been obscured by the over-seriousness of our approach.’

The seriousness he refers to perhaps stemmed from what he describes as a ‘teenage obsession’ with the work of Jerzy Grotowski, and the intensive training and practice he subsequently followed, through encounters with Zygmunt Molik and Jolanta Cynkutis in the early 1990s, and then later with Workcentre in Pontedera (Italy) and in Serbia. ‘But it was always as much about his thinking as the training,’ he says. ‘What has remained are the exercises plastiques and the emphasis on embodied impulses that manifest as physical action. However, I have abandoned any attempt to use the formal or stylistic elements that are associated with Grotowski.’

Our week of working together always includes at least two hours of full-on physical training in the mornings, stemming from the Grotowski plastiques and the principles of MCT – mutuality, contact, trust – but no doubt moulded into his own way of working by Jonathan. Both he and Nwando set high standards, but with a respectful approach. We are discouraged from zoning out, giving up, or stopping to take slugs of water constantly, instead encouraged to discipline ourselves to stay present and engaged with the physical action, although adapting moves if need be to suit our own personal abilities (much appreciated by this older performer, for one!).

I have only a very superficial experience of Grotowski’s training methods, but I’ve done a fair amount of Lecoq / Decroux based corporeal mime, and see analogies in the work. And indeed, crossovers with other training methods I’ve experienced: with Indonesian performer Parmin Ras, in Butoh practice, and in work with 5 Rhythms creator Gabrielle Roth. Perhaps it’s unsurprising that so many practices worldwide focus on the exploration of ways that different body parts can lead movement, and the power of metaphor and visual imagery in the process of movement practice – but I’m always delighted to encounter correspondences between forms across the globe and across artform practice. One memorable image that Jon uses is that of a stag caught in a bush, encouraging us to move our heads to free our antlers. In another moment, we explore the movement of the hands, and the encountering of different weights and resistances. We move giant ice blocks across the space, but then put our hands out to experience the sensation of expecting to find a wall behind a curtain only to encounter none there.

Often in the morning training there is a kind of gentle pass-the-baton between Jon and Nwando. They do this with the ease of a longterm working relationship – having both met in the Para Active days, just before Jonathan left the company, they re-met and resumed their work together in 2012, after a gap of six years. Having reconnected, they formed MAS, with the aim to create work from a wide range of influences, co-creating, with Jon as director and Nwando as performer in her alter-ego, Lady Vendredi. ’The moniker “secular ecstatic art” sums up the approach,’ says Jon, ‘we are creating an emotionally and politically charged vernacular theatre with a fluid relationship between artforms, combining the immediacy of music and the conceptualism of Live Art with theatre and ritual.’

When it’s Nwando turn to lead in the morning training, she often takes the movement work seamlessly from the Grotowski-inspired practices into her own extraordinary and exciting explorations of elements of Vodou (aka Voodoo, although the former is the preferred spelling) dance and ritual, learnt from here own teacher and mentor Zsuzsa Parrag.

We thus find ourselves gently undulating in movements inspired by the Yanvalou dance. In no way an attempt to imitate a trance-like experience, we are nevertheless striving to find a kind of opening of the heart – a release and connection that forges us into droplets of one ocean. And indeed, much of the imagery we are offered by Nwando is watery: feeling ourselves to be part of the rolling of the waves, a universal wave in fact, or placing ourselves under a waterfall and feeling the water wash over us. Again, I find myself reminded of corporeal mime (be the thing, don’t imitate the thing) and of Butoh (work from the inside out).

In other Vodou-inspired sessions, we explore movement and gesture inspired by the honouring of the Lwa (spirits) – and the Banda dance that evokes the disruptive spirits of the dead known as Ghede. These Ghede are mischievous creatures who embody and exploit all the known vices – and probably a few we haven’t yet discovered. When they arrive in the room they are loud, rude, rampantly sexual, and a great deal of fun, encouraging those in the land of the living to throw aside their inhibitions and let loose on the dancefloor. When using this material, Nwando is clear about her intention: ‘Most of the work we do with Vodou is purely training,’ she says, ‘we don’t seek to replicate Vodou rituals. We’re not creating folk art or purporting to present anything authentic.’ That said, there are some present in the group who feel a slight unease about tampering with the spirit world!

The Haitian Creole word Vodou comes from Vodun, a word meaning something like ‘mysterious invisible powers that intervene in human affairs’; or as more simply put in the Fon language, ‘spirit’. Haitian Vodou keeps alive the theology and spiritual practices of West African cultures, and Vodouists believe in a distant and unknowable supreme creator, Bondye (derived from the French term Bon Dieu, meaning Good God). As this supreme being does not intercede in human affairs, Vodouists instead communicate with (and sometimes worship) the spirits who are subservient to Bondye, the Lwa.

Although few people in the UK have had direct experience of working with Vodou, many have encountered the archetypes secondhand, through Carnival, or even through Mondo film and B-movies (which were Jon’s way in!). The one that everyone has heard of is Baron Samedi, often depicted as a grinning skull in a top hat, sporting a fat cigar and a glass of Bourbon. The Baron’s wife is Maman Brigitte, who drinks rum infused with hot peppers, and is symbolised by a black rooster.

Amongst the more esoteric higher spirits are archetypal figures whose attributes resonate throughout many cultures. Ezili is the spirit of love, beauty, jewellery and dancing who has a direct correspondence with the Afro-Brazilian Candomble spirit Oxum. One of her husbands is Ogou, known as Ogun, in Afro-Brazilian Candomble. He’s a warrior spirit, often syncretised with the Christian Saint George.

Of course there is a discussion far outside the reaches of this article about the extent to which such archetypal spirits, saints or deities are universal to all human cultures, and to what extent they originate in one part of the world then get transported – through trade and cultural exchange, or through slavery and missionary conquest. What we can reflect on here is how Nwando, who is herself of Nigerian heritage (West Africa is usually cited as the source of Voudou, exported to Haiti through the slave trade), has encountered Vodou and developed it in her own performance practice:

‘For me it is a precious gift that my teacher Zsuzsa Parrag was gifted by her teacher, who told her to teach it in Europe. It is a way to get in touch with the inner self, the space around one, the partners in the space (audience/performers). It takes you to your centre and outside of yourself. It connects with fundamental, truthful gesture, action and movement. It is evocative.’

Nwando says that Vodou came into her life almost by accident: ‘At least, I didn’t realise I was searching for it. As is the cliche for children of a diaspora, I was trying to connect to my roots in the ways I understand – through dance, through music, through social ritual. This took various forms – from making a dance-off music video with my family (the video Beat Freak which featured around 40 people, from 2 year olds to 80 year olds) to talking to relatives about social rituals and customs. Maybe I didn’t search hard enough, but I felt disheartened with what I found. Relatives feared the word “ritual” because of connotations with witch doctors and pre-colonial religion. I found it difficult in London to find much beyond a generic African Dance or Afro Fusion, which although brilliant fun, I found dissatisfying for the research that I’m interested in. Imagine if somebody went to Tokyo and taught “European” dance – where on earth would you start? How insulted would you be as a Spanish person to see somebody teaching Morris dancing as a representative of them as a “European”?’

In summer 2013, keen to seek out something more specific to their needs, Nwando and Jonathan made contact with Haitian Voudou practitioner/teacher Zsuzsa Parrag, arranged to meet her, and inspired by that meeting, invited her to work with them.

‘What I found when I started working with her makes me feel quite emotional – I couldn’t imagine my life without it now,’ Nwando says, ‘It’s strange to be taught a dance which immediately brings to my mind family members and the way they move. There is an emotional connection, a feeling of coming home, whilst at the same time it is very difficult to connect to, because there are movements that you just don’t do in other dance forms or in everyday life.’

Her love of Vodou, and desire to find a way to incorporate it into her work, is very much at the heart of the creation and development of her performance persona, Lady Vendredi:

‘Lady Vendredi is a continuing collaborative creation between myself and Jonathan Grieve. She comes through various dreams and ideas I’ve had since I was a child, conversations Jonathan and I had when we first started working together in 2012 – and he was interested in Blaxploitation films and New Orleans Voodoo/Hoodoo.’

The Vendredi character has evolved through three years of training, research and development. She is performance art persona in a theatrical world. Her various origins and influences forge her into some sort of comic book super hero with connections to Nwando’s mythologised ancestral past. Through each project she adds extra layers, gaining both gender-bending and ethno-bending dimensions. For example:

‘During our training leading to a performance at Latitude Festival in 2013, she (Vendredi) added the delivery of a preacher crossed with memories of my grandma at 3am prayers. She is my alter-ego and she is a place to put the ideas I reject from the current playing of Nwando (a priestess of a religion! A believer in the spirit world!) and the discoveries we make about the world around us (from experiences in a theatre-cult to current discourses on race, cultural appropriation, white supremacy). I’ve been told I look different when I perform her…’

This notion of creating a performance persona that is some sort of freak-show cum super-hero version of the self becomes a central focus of the second half of the laboratory week. Nwando shares some of the mapping that were part of her process with Jonathan in creating Lady Vendredi – a large sheet of wallpaper on the floor is covered in words and phrases linked with connecting lines. We are then encouraged to think about how we might map our own persona. We are asked to list everything that we like about ourselves and to think about ‘self-ploitation’. Never mind what we are in our deepest, most private selves – what have we got that is valued in the wider world, and thus ‘sellable’? Physical attributes, talents, abilities, party tricks, beliefs. We are looking for the exaggerated self; the objectified self. We are also asked to think about the personal traits that we (or other people) dislike in us; to consider the unacceptable versions of our self.

And so to work. My raw material is a very white body, Celtic white (of Anglo-Irish stock), so white it’s almost blue, with eyelashes so pale you can’t see them without mascara. Long strawberry blonde hair, thick as old rope. A mature female form, matronly even. I like to be seen and heard, always put my hand up first in class. I talk a lot. I get cross easily and I’m argumentative, but I’m also a great defender of people and ideas. I use words as weapons. I am generous with food and money. I know a lot of about popular dance, and know lots of party dances, such as the Charleston Stroll and the line-dance from Saturday Night Fever. I’m vain, and a bit of a show-off. I’m short-sighted (due to a visual disability, not correctable by glasses) and clumsy. I hate people asking me why I don’t wear glasses. I’m a dilettante, a Jill-of-all-trades. I have a confused sexual history.

Left to work on all this alone, with the help of a mountain of props and costumes, I feel some analogy to the process of creating a clown or Bouffon character, and find myself (almost inevitably) drifting towards familiar territory, creating a kind of kooky tart-with-a-heart party girl who is not dissimilar to performance personae I’ve created in other situations. Which is interestingly very different to the rather earth-mothery/golden empress personae that others had modelled me into.

In other corners of the rehearsal room, all sorts of interesting beings are taking shape, evolving from this diverse group of artists of varying ages, genders, and ethnicities. A male opera singer/physical theatre performer with an interest in exploring transgender possibilities is working on creating an Ave Maria-singing cloistered and veiled being whose pent-up hysteria would give Ken Russell’s nuns in The Devils a run for their money. A young Flamenco dancer is exploiting her persona as the ‘pretty ballerina’, swathed in white net and lace with a red rose between her death, and blood between her legs. Elsewhere, I spy an ultra-hairy Valkyrie, the performer sporting an extraordinary and wonderfully lunatic number of wigs and hairpieces, not all of them on her head; a White Supremacist swigging from a bottle and tormenting a tiny doll; a trench-coated photographer snapping wildly, desperate to join the performance action; and a kohl-eyed Arabic beauty with undulating hips who is strapping a gun to her body. Meanwhile, Nwando is honing a kind of reverse-Voudou/inverted Minstrel act, in which a joyfully dancing Lady Vendredi emerges from the mock-Minstrel blacked-up/whited-up drag.

On the final couple of days, these personae are refined further, and placed in juxtaposition with each other, creating interesting inter-relationships (the aria-singing madonna/whore/nun persona and the spoiled ballerina work beautifully together, for example – especially when then partnered with a cello-playing hippy traveller). Finally, a performance script is created for the Saturday evening, which will include live music performed by Lady Vendredi and her band, ecstatic dance, solo and ensemble performance, and plenty of audience interaction. Unfortunately, I wasn’t there for the final showing, due to other commitments – but plenty of others were there, including Thom Andrewes, associate director of ERRATICA. He had this to say about what he witnessed:

‘My immediate impression was that the show was about ritual and the creation of ritualistic spaces, in which ecstatic transformations of the body become possible. I think this was very clearly, strikingly and effectively achieved on various levels, while being simultaneously problematised/critiqued, which was ideal… The ritual actions at the opening of the show—dancing, sharing food and drink – established the rough realness of the performance, i.e., if this is a ritual, we are (to some degree) involved, and it is actually happening here/now, rather than the representation of a ritual performance that was/is happening elsewhere, for an imaginary audience for whom we are standing in. This was pretty integral to what I felt throughout as the possibility of participation, as was the number of plants/performers who seemed to blend in with the audience. It was never clear to me, even at the end, exactly who was in on the performance and how much they had been expecting. I haven’t been to many events/performances of this style/approach, but I’ve been to some, and this is perhaps the first time when it’s really worked for me. I suppose it had the real feeling of a “happening”, and it was all down to the possibilities of the “ritual” form as a general frame – which is highly theatrical, governed by arbitrary yet absolutely necessary rules/laws, and also present, real and co-existing with the audience—and to the commitment of the performers to everything.’

Thom also raises a question that is always central to our work throughout the week: ‘The question of cultural appropriation, or the fact that it might seem somehow inappropriate to recreate elements of African ritual practice with white performers for a predominantly white audience in Hackney (i.e., completely separated from its cultural context) is one that remains, but I also think it is a far more complex/interesting question than most people assume…’

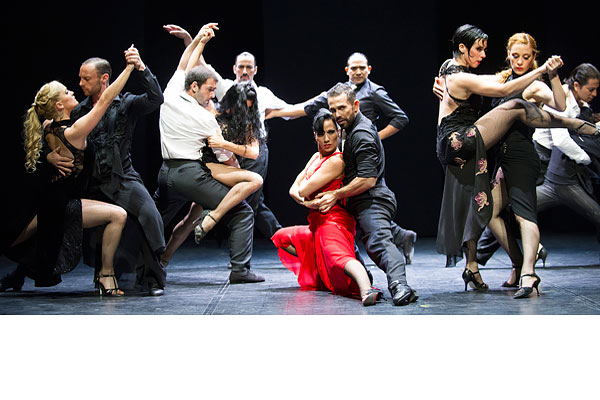

It’s something that has been explored in various ways throughout the week, and its something that comes up for me again and again in work and life. Some of the questions I’m interested in include: is there anything that belongs exclusively to one nation or culture? Argentina for example, claims tango as its own – but so does Uruguay. And tango itself is a hybrid form, bringing together rhythms, dances and musical instrumentation from Spain, Italy, Morocco, and numerous other places. Similarly, Flamenco might be thought to ‘belong to’ Spain but evolved from the coming together of influences from Kathak dance from India (brought to Europe by travelling Roma people), Arabic music, Jewish song, Andalucian folk dance and any number of other influences that converged in Southern Spain a few centuries ago.

Is there, in any case, actually any differences between ‘races’ and ‘cultures’ or is there only one race, the human race,with ‘culture’ a constantly evolving mix of influences and ideas, ever-shifting in time and space? For example, we talk of England as a Christian country, and our head of state is also head of the Anglican church, yet this religion so intrinsically tied to ‘British values’ was imported from the Middle East.

Can we ringfence religion, music, dance, language, ethics, and say ‘this is a value/idea/practice that belongs to this culture, but cannot be used by this one’, or do we all own everything? Who decides? If I want to ‘find my roots’ how far back is it reasonable to go? I’m white, Anglo-Irish – but with Jewish ancestors in there too. And that’s just what I know about. Who knows what else is in the mix. We all evolved from the same place, so I’m ultimately a daughter of Eve – and at some point, way back in time, my great, great grandmother (to the power of whatever number it might be) was a dark-skinned, black-haired African Savannah dweller. Did she once dance to the rhythms that informed the development of the Yanvalou dance that is core to Voudou practice? Or does this practice now ‘belong to’ Haiti, not to the Igbo of West Africa?

Jon acknowledges that these are thorny issues – and reflecting after the event, Nwando has these thoughts to share:

‘I think it’s really important, as an artist, that I have the freedom to self define – to not limit myself to people’s ideas of what I should be presenting, hiding or showing. Through the work we do I hold up the various contradictory aspects of my being (real, imagined, projected onto me by society, authentic, fake) and explore them.’

Jon adds: ‘My own approach is fairly simple and is summed up by this quotation from the psychologist Clare W Graves: “Damn it all, a person has a right to be who he is.” When that is tested against the complications of various power structures and dogmas, we get a range of diverse results.’

Thinking back over the week, so much has stayed with me. One of the most intense and fruitful sessions saw the creation of a whole-room shrine, in which each of us entered the space one by one, chose an object and placed it in the designated area, building and building until we’d created a wonderful, composite artwork that incorporated furniture, fabrics, props and objects of all sorts, including many that we’d brought ourselves to make use of. There, dangling from a shelf is one of my blue satin Latin tango shoes. On the other side, a handful of shells (the casings of long-dead sea creatures) collected from Brighton beach when my children were still small enough to go to the beach with me. Next to them, a lurid pink feather fan that I bought in Rio during Carnival (although like most Carnival products in Brazil, it was made in China). The stories these objects of mine represent are multiple and complex, and they are just a tiny fraction of the heap of objects arrayed here.

After we’ve finished our making – and with no signal or voiced decision to do so – we all find ourselves dressing in anything that we can find that we take a shine to (Jon is wearing a giant whoppee cushion costume, but that’s the least of it), and dancing exuberantly in a circle of call-and-response sounds and actions. It feels good and right – reverent and irreverent at one and the same time, an invented ritual that has arisen from the energy of the moment – but aren’t all rituals just that?

I will leave the last word with Nwando: ‘As I understand it, Vodou is an incredibly dense, non-dogmatic, ancestral, joyful practice of which most people outside of Haiti are wholly ignorant and many people (particularly black people) are afraid. As an atheist I have no fears of any religion but I do have a profound respect for ritual practices connected to mythology and am particularly interested in ones that contain ecstatic dance. And Vodou mythology is up there with the best myths you care to name!’

Footnotes:

Featured photo (Top) by Rafaela Rocha. Other images throughout as credited.

MAS: Secular Ecstatic Art – a week-long laboratory and performance took place at Apiary Studios, Hackney Road, London, 15–20 June 2015. It was facilitated by Nwando Ebzie and Jonathan Grieve of MAS Productions.

Battle Cry, a public performance by Lady Vendredi and participants in the week’s work, co-produced by MAS and NitroBEAT, took place at Apiary on the evening of Saturday 20 June 2015.

MAS Productions have announced that the ongoing Lady Vendredi project has received Arts Council England funding, and a new stage of research and development will culminate in a public performance at the Roundhouse, London, on 22 October 2015.

For more see http://www.nwandoebizie.com/ and http://www.jonathangrieve.com/