Dorothy Max Prior goes to Fierce Festival in Birmingham and finds a city re-imagined

A speaking garden, a deconstructed car, a nail bar, and a sit-down meal with a bunch of pre-teen boys. Passive consumption not an option – we’re here to engage, to interact.

The opening weekend of Fierce Festival 2014 took its audience out and about into all sorts of far-flung corners of Birmingham and beyond. Getting from one site to another proved to be something of a psychogeographic experiment, one big drift into ever more peculiar environments: all large cities are an architectural pick-and-mix, but Birmingham beats anywhere else in the UK hands-down for its extraordinary mix of streets that morph into shopping centres, buildings stranded on traffic islands, and desolate subways and footbridges that don’t seem to lead anywhere in particular.

But the feeling of being a bit-player in a film about urban displacement just added to the artistic adventure, and after 24 hours, I felt I had some grip on the geography of the place – despite the suspicion that some strange dream-war morphing of space was happening.

So, approaching the documenting of this visit from a geographical perspective, I’m going to start at the centre and work out.

Phoebe Davies: Influences. Photo James Allan

Bang in the heart of the city, in Centenary Square off Broad Street, is the new library, which is celebrating its first birthday in October 2014 – a great aircraft hangar of a building with a postmodern-playful silver and yellow exterior, its circular inside space kitted out with LED–lit escalators that offer a panoramic view of the rainbow arcs of bookshelves inside and the hotch-potch cityscape outside. This Fierce Fest opening weekend is also Birmingham Literature weekend, and Fun Palaces weekend – so a row of desks promoting the various artistic wares on offer are lined up in the foyer. What I’m here for is Phoebe Davies’s Influences: The Nail Bar. How it works: you turn up, get assigned to a nail bar art worker (one of a team of teenage girls), and given a menu of nail wraps – a series of ten nail-sized portraits of women being honoured (for the Fierce season, women from Birmingham and the Midlands). Who to pick? I consider Mashkura Begum, director of the Birmingham Leadership Foundation, who is ‘passionate about championing young leaders’, or Jasvinder Sanghera, founder of Karma Nirvana, an advocate for women experiencing forced marriage or honour-based abuse but in the end I plump for Justice Williams, a writer and editor who has set up her own social enterprise scheme to support disadvantaged youngsters affected by gang culture. Getting the wrap is a pretty minimal experience, but if you ask, you can get the rest of your nails painted too – although, it has to be said, this isn’t done that meticulously, which is a bit of a disappointment! I’m not a manicure sort of person, so I had high expectations. But that, I know, isn’t the point: this is a piece that is less about the execution of the chosen interface – nail art – than the process of engagement with the community involved in the workshops that lead up to it. Phoebe Davies works with local community leaders (in this case, the Birmingham-based Sister Act) to locate or create a working group of young women. The group meet to debate female expectations and current attitudes to feminism, and to learn how the artwork will evolve. Out of that process comes the research and choosing of suitable candidates for the nail wraps. All this we are encouraged to speak about with our assigned nail art worker. As the piece has been performed in many different locations, there is also the value of the accumulation of research across the country.

Mammalian Diving Reflex: Eat the Street. Photo James Allan

From 13-year-old-girls to 12-year-old boys, a whole world apart. The next location on our city map is Piccolino’s restaurant, in a pedestrianised and somewhat sterile area just around the corner from the library, which has been taken over for the Saturday lunchtime slot by Eat the Street, a project brought to Fierce by the always enterprising Canadian company Mammalian Diving Reflex (other works include Haircuts by Children and The Children’s Theatre Awards). The premise is simple: a group of children (in this case, year 7 boys) are trained up as restaurant critics. They have notebooks and cameras, and audience members are invited to sit with them to share the experience of dining and critiquing. The outcome is wonderful: I can’t remember the last time I had so much fun at a dinner party. I struck lucky with Jack and Shea who, if they don’t become famous footballers (they are both in the school team) or rock stars (they both play in a band), will almost certainly become a famous comedy duo. Our intrepid twosome quiz their fellow diners (‘You looked extravagant’ says Shea, explaining why I was encouraged to join his table), regale waiters who forget to bring the garlic bread, amuse us with stories of the most unusual things they have eaten (kangaroo, it turns out) or of Instagram faux pas, and eventually start a revolution against the fixed menus for children, chanting ‘ ‘SET MENUS ARE PANTS’ when they are told they can only choose between vanilla or chocolate ice-cream, and can’t have the cracked caramel copa with amoretti biscuits. I’m an enormous fan of this company – and dear reader, am in fact a recipient of a Mammalian Diving Reflex Children’s Award – a lovely chocolate trophy won at the Norfolk and Norwich Festival a few years ago. ‘The only problem with the chocolate trophies,’ says company director Darren O’Donnell, ‘is that they get eaten by mice’. A suitably surreal note on which to end a delightful dining experience.

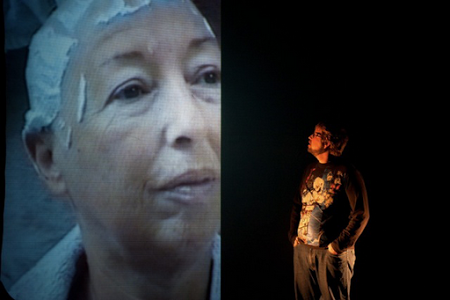

Tania El Khoury: Gardens Speak. Photo Jesse Hunnford

Circling outwards: to the north-west of the city is the old Jewellery Quarter of St Paul’s, a pretty area with cobbled streets and warehouses put to new uses as hotels, restaurants or vintage clothing shops. Here, in the AE Harris building (an old metal factory) is where we find Tania El Khoury’s Gardens Speak, an interactive installation which honours the lives of ten Syrian martyrs. In a waiting room, audience members are asked to take off shoes and socks, and to put on a hooded plastic mac. We are invited to choose a card from a basket – mine gives the name Abu Khaled – and led into the dark installation space. A large soil-filled plot bears ten gravestones, written in Arabic. First task is to identify our assigned martyr, shining torches onto names written in the unfamiliar script. Once found, we kneel at the ‘grave’ and dig, ear to the ground, unearthing the story coming from a buried speaker. To hear what’s being said, you need to really scrabble down in the earth, then to lie down, ear close to the ground. It’s dark and damp and the smell of the soil evokes powerful memories: my parents’ burials; gardening with my children. Abu Khaled, I hear, is just 40 years old at the time of his death. He (or rather, the storyteller playing him) calls me ‘my child’, which I like – even though I’m old enough to be his mother. We are all children of God. Abu, I learn, is a shopkeeper, not a soldier – a kind family man who gives crisps and cola to the local kids, killed instantly by a piece of shrapnel as he closed up shop for the night. I’m hearing this story on the day the news of Alan Henning’s murder is announced, and both become linked in my mind – the unbearable sorrow of those who remain, the terrible loss of these two lives, both kind and gentle men in their 40s more interested in caring for children than in fighting wars. One man whose name and image is currently racing around the newspapers and TV channels of the world; one whose name is little known, buried in a grave in a private garden in Syria – apparently funerals are often targeted by Assad’s troops and graves desecrated, so burials are frequently kept secret. Tana El Khoury’s use of the term ‘martyr’ for her subjects reminds us of the original meaning of the word: one who bears witness, or gives testimony. Her work has honoured lives which would otherwise be unknown to us – as the horrendous statistics of the dead and displaced of Syria continue to dominate the news, it is good to be placed in direct engagement with the human stories behind the terrible stats. There’s an odd tug between reality and artifice in this voicing of words placed in a dead man’s mouth, but although it is a fictionalising of a story that can never be told by its protagonist, I feel I have met Abu Khaled.

Jo Bannon: Exposure. Photo Manuel Vason

Right across the map, in the south-east corner of the city, in a raggle-taggle area of coach stations, disused buildings, and muralled walls is The Edge, a rough and ready artist studio space that is put to use as the Fierce Festival Hub: pop-up café, late-night bar, and a venue for some of the work – including Jo Bannon’s Exposure. Small-scale one-on-one performance with autobiographical content is probably the fastest-growing form of practice within contemporary live art. Anyone who has been to the National Review of Live Art will have experienced scores of these encounters. All this a prelude to saying that it is a pleasure to see the form used well. Exposure tells a small but perfectly formed story – a story of looking and being looked at, exploring the difference between looking and seeing. Using recorded text (Jo Bannon’s words, which she chooses to relay mediated rather than live, for reasons she explains to the listener), and an interplay between darkness and focused bright light, the piece reflects on the artist’s life as someone born with almost no pigment in her retina (‘albino’ in the common parlance). The childhood experience of being stared at in public spaces, of being aware that she is different to her sister, the subject of scientific study, is subverted as we are invited to look, to see, to be looked at, to be seen. Not to flinch from seeing and from being seen for what we are. Just 5 minutes long, but a timeless experience, rich and resonant.

Dina Roncevic: Car Deconstructions. Photo James Allan

Even further afield, at a car mechanics’ workshop in Digbeth, an area of old warehouses and brick railway arches that is fast becoming a destination for artists and makers, Croatian artist and car mechanic Dina Roncevic and her team of 10- to 12-year-old girls are busy with Car Deconstructions, which is pretty much what it says on the can. The girls have received some rudimentary training in mechanics and coachworks, and over three days dissemble a car down to its component parts. In the front of the garage, a pile of wheels, fenders, nuts, and bolts is building up. Behind the pile is the car, with a crew of girls in boilersuits happily pulling bits apart, under Dina’s guidance. In a cage to the side, a laconic male mechanic focuses on his paperwork. (I presume he’s not necessarily part of the artwork, but his silent, unconcerned presence feels important.) Issues of social identity and gender roles are at the heart of the artist’s work. It’s a conceptually and visually interesting piece, and one which I think would be good to return to a number of times to witness the process from whole car to dissembled parts, although sadly I only have time for one short visit. I perhaps ought to add, on a personal note, that my father was a car mechanic, so I felt no sense of discomfort or alienation in this ‘masculine’ environment – on the contrary, it felt like home.

Forced Entertainment | Tarek Atoui: The Last Adventures. Photo James Allan

And finally, beyond the city limits… Warwick Arts Centre might perhaps stretch the boundaries of Birmingham a little further than most would consider reasonable, but this was for the UK premiere of Forced Entertainment’s The Last Adventures, so a hefty contingent of Fierce attendees made the perilous rush-hour journey by train to Coventry, then stuffing into a convoy of taxis to wend their way at a painfully slow rate out of the city and across the university’s rambling campus. It was a close shave but we got in just as the show went up.

The Last Adventures sees the return to the large-scale and epic for Forced Entertainment, who have created the piece in collaboration with Lebanese sound artist Tarek Atoui. It features a cast of 12 (company members Richard Lowden, Claire Marshall, Cathy Naden and Terry O’Connor, and a team of guest performers, including Mark Etchells) and each new location adds in a guest musician – in this case, Japanese electronica/’cosmic noise’ artist KK Null. As far as I can gather, Tarek Atoui has created the base score, and each invited collaborating musician is free to create whatever sound design they wish to place over this, with a very short rehearsal period for the elements to be integrated. Shades of Merce Cunningham and John Cage, perhaps? Certainly, the concept reminds me of Cage’s Music-circus, in which no notes or forms of music are prescribed in the composer’s set of instructions to guest musicians.

At the start of the piece, we see two performers sitting on chairs, facing the other ten, also sat on chairs, classroom style. There is a long call-and-response section, a typical Forced Ents list of things that are both foolish and philosophical: ‘A bridge cannot apologise’ says a caller, and back comes the parroted response: ‘a bridge cannot apologise’. Sometimes there are tongue-in-cheek word plays and inversions: ‘People eat animals’ and ‘animals eat people’. Sometimes a line is repeated as a kind of chorus: ‘Everything that can go wrong will go wrong. Everything that can go wrong will go wrong. Everything that can go wrong will go wrong’. Shards of intense electronic sound cuts through the words. After a while, people leave, one chair after another taken away. The voices stop. A forest of plywood trees takes their place. And from then on in, there is no more text – there is sound from KK, and there is visual imagery and physical action, as the company play out a seemingly chaotic treatment of familiar storybook tropes and archetypes – kings and soldiers, princesses and dragons. In one of the strongest scenes, a childish war-game erupts – all overcoats, tin-pot helmets, broom-handle bayonets, and red ribbons streams of blood. It’s stupid, funny and heartbreaking all at once. This is a show in which the company’s dressing-up box plays a central role, raided for trusty old favourites familiar from earlier shows. The skeleton costumes get an airing in a really lovely scene that plays (again, in childhood war-games mode) with obedience and disobedience. A favourite moment sees the arrival onstage of a wonky robot, standing in an uncertain way downstage before careering round wildly, losing its head, and eventually crashing. Meanwhile, Medieval maidens skip around the space, and a disjointed dragon weaves through them. The forest of trees with legs comes and goes, as does a set of similarly animated 2-D waves and clouds. The deliberately low-key, hamster-wheel-treading performance mode of the ’dancing scenery’ animators becomes tiresome after a while – no doubt tedium is the point, but it feels like we’ve been here before, and the joke wears thin. Perhaps in the massive space that the work was created in (an old coal mine in Germany), there may have been a different visual effect – a kind of Myth of Sisyphus depiction of endless travail, perhaps – but here (despite this being a good-sized stage) it just looks cramped. For the most part, KK’s contribution is a brilliant aural assault of electronic drones, and ear-splitting screeches that erupt beautifully from moments of silence. Occasionally, sampled sounds are used, and these feel rather too illustrative. It is hard to know how much of Tarek Atoui’s work remains in the current version of the piece, or whether at this stage his contribution is more the conceptual idea of an ongoing collaborative relationship between Forced Entertainment and each guest musician. It would be good to see the piece a second time with a different guest musician to really understand the nature of the collaboration better. It would also be great to see it staged in the UK in a similar environment to the space in which it was created. Theatre stages just feel too limiting for this scale of work. Location is everything!

Fierce Festival, 2–12 October 2014. Dorothy Max Prior attended the opening weekend, 3–4 October 2014. For all events and information see www.wearefierce.org

Go wild in the country! A reflection on artistic escape from the bright lights, big city – and a tale of two Feasts An ensemble of actors are gathered together to research the basic components of their craft in a workshop setting. The director gains inspiration from Japanese Noh Theatre and Commedia Dell’Arte. He expresses a desire to work with a bare stage, free from the trappings of cumbersome naturalistic stage sets. He views his work as a spiritual process that re-establishes theatre as a sacred space, and he is feeling increasingly frustrated with the demands of making work in a cosmopolitan setting. He longs to escape from the city…. The scene described above would not be too unusual today, but far from the usual expectations and practices of the theatre of its day, for this is Paris 1913. The director is Jacques Copeau, and the company is the Vieux-Colombier, which he has set up as a research project with the intention of restoring theatre to a purer art form of poetry and vision, based on the actor’s skill and inner strength. His influence on the physical and devised theatres of the twentieth century is phenomenal: from Copeau we can trace the line of influence through Antonin Artaud, who worked with Jean-Louis Barrault, one of Copeau’s dedicated pupils. Another of the dedicated troupe was a young working-class man called Etienne Decroux, who was to become known as the father of modern mime. Copeau’s daughter Marie-Helene befriended a young gymnast called Jacques Lecoq and through her, Lecoq had his introduction to theatre. The most radical phase of Copeau’s work took place when he decided in 1924 to leave the Parisian theatre world; to turn his back on the venues and producers and set-builders and first nights in the quest to find a different sort of theatre. Taking members of both the Vieux-Colombier company and its school he moved to Burgundy to create a theatre community that lived and worked together, celebrating birthdays with ritual, growing their own organic food and creating theatre pieces which were toured in the commedia dell’ arte tradition – playing outdoors in village squares, an integral part of the rural life that they had embraced.

Go wild in the country! A reflection on artistic escape from the bright lights, big city – and a tale of two Feasts An ensemble of actors are gathered together to research the basic components of their craft in a workshop setting. The director gains inspiration from Japanese Noh Theatre and Commedia Dell’Arte. He expresses a desire to work with a bare stage, free from the trappings of cumbersome naturalistic stage sets. He views his work as a spiritual process that re-establishes theatre as a sacred space, and he is feeling increasingly frustrated with the demands of making work in a cosmopolitan setting. He longs to escape from the city…. The scene described above would not be too unusual today, but far from the usual expectations and practices of the theatre of its day, for this is Paris 1913. The director is Jacques Copeau, and the company is the Vieux-Colombier, which he has set up as a research project with the intention of restoring theatre to a purer art form of poetry and vision, based on the actor’s skill and inner strength. His influence on the physical and devised theatres of the twentieth century is phenomenal: from Copeau we can trace the line of influence through Antonin Artaud, who worked with Jean-Louis Barrault, one of Copeau’s dedicated pupils. Another of the dedicated troupe was a young working-class man called Etienne Decroux, who was to become known as the father of modern mime. Copeau’s daughter Marie-Helene befriended a young gymnast called Jacques Lecoq and through her, Lecoq had his introduction to theatre. The most radical phase of Copeau’s work took place when he decided in 1924 to leave the Parisian theatre world; to turn his back on the venues and producers and set-builders and first nights in the quest to find a different sort of theatre. Taking members of both the Vieux-Colombier company and its school he moved to Burgundy to create a theatre community that lived and worked together, celebrating birthdays with ritual, growing their own organic food and creating theatre pieces which were toured in the commedia dell’ arte tradition – playing outdoors in village squares, an integral part of the rural life that they had embraced.

A man spins round and round: a whirling dervish with one arm raised; a Mensch-Maschine; a clockwork toy. His image is reflected in the Spiegeltent mirrors all around him, so that the lone figure seems to have a ghostly chorus of identical automata. Shadows are cast onto the roof of the tent, another chorus of echoes. A woman enters the space, standing at the other end of the narrow runway that divides the space in two – a witness watching him and watching us, the audience, who are sat in traverse. We are close enough to hear her breathe; to see her eyelids flicker; to note the muscles of her body tightening and relaxing. And then there are four, who burst into a sequence of acrobatic tumbles, twists and turns using the whole length of the ‘catwalk’ staging, the contact mics attached relaying the percussive thuds of feet that hit the heartbeats of the soundtrack. And so we’re off and running into the second ensemble show by young Australian circus company Casus, whose first show Knee Deep has toured extensively worldwide with phenomenal success. In Finding the Silence, the company build on the key qualities of the first piece – top-notch core skills, complicity, tender relationships, a desire to approach equipment and objects on their own terms, without seeking to establish unnecessary or fussy theatrical metaphors – and yet strive to continue the artistic investigation, to step out into brave new worlds. The first radical and brave decision is to play the show on this narrow runway, the audience on both sides breathtakingly close to the leaping, stretching, climbing bodies. I’m astonished to learn afterwards that this, the European premiere of the show, is actually the first time they’ve performed it in traverse – it was presented end-on when premiered earlier this year in Australia. I’m here in Canterbury on the opening night, and the atmosphere is electric – every move seems to be set on a precipice. I’d urge Casus to keep the traverse, terrifying though it is – it feels so wonderfully challenging, so radically different. And there are many great and wonderful risks taken on this precarious performance space – not least a duet between two blindfolded men, aided and abetted by their seeing seconds… Feel the fear and do it anyway could be the leitmotif of this show. The intense physical action throughout is given an oddly dreamlike quality by the show’s soundtrack, a great, organic ocean of sound which pulses with subdued beats and riffs mixed with samples of at-times almost subliminal voices and sounds. Having seen Jerk, the solo show by Casus’ only female member and co-founder, Emma Sarjeant, I can appreciate some affinity between these very different shows: both seem to be playing out the internal conversation and/or subconscious perceptions and emotions of the performers who, despite the intense, visceral earthiness of the work, often have an air of other-worldliness about them. Sometimes we seem to be in the realms of the gods, and at other times firmly on earth. There are recurring images of cradling and supporting – as, for example, in a gorgeous duet between Jesse Scott (who also directs this show) and Lachlan McAulay. Acrobatics, handstands/shoulder stands, and balances or counter-balances of one sort or another are the company’s core skills and there’s plenty of dazzling examples on show here, all thrillingly close so we really feel the force as well as see the fabulous shapes created – for example, in towering three-high stands, walks across heads, and perpetual-motion cartwheels. The piece conjures up associations with Meyerhold’s Biodynamics, the team creating images with their bodies of turning cogs or machine parts that arise and dissolve fluidly. Planks and benches are dragged onto the runway, the human bodies interacting with the objects in ways that seem to make them all one harmonious whole. At one point, the heaped-up pile of wooden junk surprisingly turns itself into a teeterboard. At another, there’s a particularly beautiful handstand-on-a-bench sequence by Emma Serjeant and Casus’ new boy Vincent Van Berkel, who has stepped into the shoes of injured founder member Natano Fa’anano magnificently. Far more than a stand-in, he has carved a niche for himself in the company, and contributed magnificently to Finding the Silence. It’s not all acro – there’s aerial too, including some perfectly fine solo trapeze, and (more interestingly) some imaginative foot-sling work from Jesse. But the best is an ensemble corde lisse sequence that plays on the company’s strengths – the soft and tender gender-challenging relationships between the four of them played out, as bases and flyers merge and swap in a gorgeous tangle of rope, limbs and torsos. What a beautiful meeting of very different bodies these four performers create! There are some wobbles and failed moves – although, perhaps perversely, I love the humanity of these moments. In a show that sets itself up to investigate individual vulnerabilities and inner fears, such moments feel poignant – emotional successes rather than physical failures. I’m pretty sure the circus-savvy audience here at the Spiegeltent agree: they are as quiet as mice throughout, still and attentive, rather than cheering the tricks – there’s almost a collective holding of breath let out in a tumultuous round of applause at the end. (And a nod of appreciation here to the Canterbury Festival, who programmed not only Finding the Silence, but also two other shows by Casus: Emma’s Jerk, and the three-man piece for young audiences, Tolu. Great to see a circus company really embraced and supported in this way.) So, so much to like and admire – yet it is early days. It is stating the obvious to say that a complex circus show this young needs to bed in – particularly if the staging is changed so dramatically. Although in saying this, I’m hoping that it loses none of its dynamism and risk in its settling-in process. There are criticisms, but they are minor. The odd, jodhpur-style patched costumes are a distraction. There are a few transitions that need reworking, and the general frame and shaping of the piece needs a bit of dramaturgical carpentry here and there. But that’s all to be expected at this stage of the process: Casus have a corking new show launched, and the world is their oyster.

A man spins round and round: a whirling dervish with one arm raised; a Mensch-Maschine; a clockwork toy. His image is reflected in the Spiegeltent mirrors all around him, so that the lone figure seems to have a ghostly chorus of identical automata. Shadows are cast onto the roof of the tent, another chorus of echoes. A woman enters the space, standing at the other end of the narrow runway that divides the space in two – a witness watching him and watching us, the audience, who are sat in traverse. We are close enough to hear her breathe; to see her eyelids flicker; to note the muscles of her body tightening and relaxing. And then there are four, who burst into a sequence of acrobatic tumbles, twists and turns using the whole length of the ‘catwalk’ staging, the contact mics attached relaying the percussive thuds of feet that hit the heartbeats of the soundtrack. And so we’re off and running into the second ensemble show by young Australian circus company Casus, whose first show Knee Deep has toured extensively worldwide with phenomenal success. In Finding the Silence, the company build on the key qualities of the first piece – top-notch core skills, complicity, tender relationships, a desire to approach equipment and objects on their own terms, without seeking to establish unnecessary or fussy theatrical metaphors – and yet strive to continue the artistic investigation, to step out into brave new worlds. The first radical and brave decision is to play the show on this narrow runway, the audience on both sides breathtakingly close to the leaping, stretching, climbing bodies. I’m astonished to learn afterwards that this, the European premiere of the show, is actually the first time they’ve performed it in traverse – it was presented end-on when premiered earlier this year in Australia. I’m here in Canterbury on the opening night, and the atmosphere is electric – every move seems to be set on a precipice. I’d urge Casus to keep the traverse, terrifying though it is – it feels so wonderfully challenging, so radically different. And there are many great and wonderful risks taken on this precarious performance space – not least a duet between two blindfolded men, aided and abetted by their seeing seconds… Feel the fear and do it anyway could be the leitmotif of this show. The intense physical action throughout is given an oddly dreamlike quality by the show’s soundtrack, a great, organic ocean of sound which pulses with subdued beats and riffs mixed with samples of at-times almost subliminal voices and sounds. Having seen Jerk, the solo show by Casus’ only female member and co-founder, Emma Sarjeant, I can appreciate some affinity between these very different shows: both seem to be playing out the internal conversation and/or subconscious perceptions and emotions of the performers who, despite the intense, visceral earthiness of the work, often have an air of other-worldliness about them. Sometimes we seem to be in the realms of the gods, and at other times firmly on earth. There are recurring images of cradling and supporting – as, for example, in a gorgeous duet between Jesse Scott (who also directs this show) and Lachlan McAulay. Acrobatics, handstands/shoulder stands, and balances or counter-balances of one sort or another are the company’s core skills and there’s plenty of dazzling examples on show here, all thrillingly close so we really feel the force as well as see the fabulous shapes created – for example, in towering three-high stands, walks across heads, and perpetual-motion cartwheels. The piece conjures up associations with Meyerhold’s Biodynamics, the team creating images with their bodies of turning cogs or machine parts that arise and dissolve fluidly. Planks and benches are dragged onto the runway, the human bodies interacting with the objects in ways that seem to make them all one harmonious whole. At one point, the heaped-up pile of wooden junk surprisingly turns itself into a teeterboard. At another, there’s a particularly beautiful handstand-on-a-bench sequence by Emma Serjeant and Casus’ new boy Vincent Van Berkel, who has stepped into the shoes of injured founder member Natano Fa’anano magnificently. Far more than a stand-in, he has carved a niche for himself in the company, and contributed magnificently to Finding the Silence. It’s not all acro – there’s aerial too, including some perfectly fine solo trapeze, and (more interestingly) some imaginative foot-sling work from Jesse. But the best is an ensemble corde lisse sequence that plays on the company’s strengths – the soft and tender gender-challenging relationships between the four of them played out, as bases and flyers merge and swap in a gorgeous tangle of rope, limbs and torsos. What a beautiful meeting of very different bodies these four performers create! There are some wobbles and failed moves – although, perhaps perversely, I love the humanity of these moments. In a show that sets itself up to investigate individual vulnerabilities and inner fears, such moments feel poignant – emotional successes rather than physical failures. I’m pretty sure the circus-savvy audience here at the Spiegeltent agree: they are as quiet as mice throughout, still and attentive, rather than cheering the tricks – there’s almost a collective holding of breath let out in a tumultuous round of applause at the end. (And a nod of appreciation here to the Canterbury Festival, who programmed not only Finding the Silence, but also two other shows by Casus: Emma’s Jerk, and the three-man piece for young audiences, Tolu. Great to see a circus company really embraced and supported in this way.) So, so much to like and admire – yet it is early days. It is stating the obvious to say that a complex circus show this young needs to bed in – particularly if the staging is changed so dramatically. Although in saying this, I’m hoping that it loses none of its dynamism and risk in its settling-in process. There are criticisms, but they are minor. The odd, jodhpur-style patched costumes are a distraction. There are a few transitions that need reworking, and the general frame and shaping of the piece needs a bit of dramaturgical carpentry here and there. But that’s all to be expected at this stage of the process: Casus have a corking new show launched, and the world is their oyster.