A big white yurt stands in a quiet Edinburgh square off the beaten track of the Fringe. This is the Chapiteau, and inside is a floor of soil and a circle of wooden benches. We are here for the circus – although this isn’t any sort of regular circus – it’s a piece of word-free circus theatre by French company T1J exploring the troubled childhood of sculptor Jephan de Villiers, whose work mostly takes the form of wood-carving. We know this last fact because someone announces it pre-show, in the midst of the housekeeping notes about mobile phones and photography.

Not ideal, as it is good to get one’s theatre content from the piece of theatre presented, not from a pre-show announcement. So it is hard to say whether that starting point and theme would have been clear or not without being told, as once told you know, and that is that. Perhaps it is because this sculptor is better known in France than in the UK so it is felt that we need this context? Anyway, no matter – what is clearly presented, using puppetry, acrobatics and visual imagery, is a story of a small child who wavers between wonder at the world and distress; an exploration of childhood joy and pain.

We start with an axe-man chopping into a large log – really chopping, pieces flying off into the audience. A puppeteer and her puppet (carved wood, attached to her feet, with her hands as his) appear. The puppet-boy is a kind of Pinocchio figure who is intrigued by his own wooden-ness and seems to want to become flesh and blood – stroking the leg of his puppeteer (Morgan Aimerie Robin) with obvious interest in the warm, living material that it is moulded from. The puppet-boy wanders round the space, peering through thick-lensed glasses at anything that takes his childish interest – my bag is stolen and rummaged through, my water given to someone else. When his glasses drop off, he steals someone else’s.

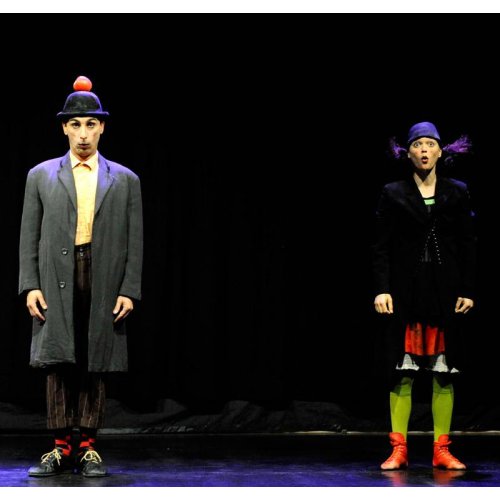

Playing around and sometimes against the puppet-boy are a trio of acrobats, two men and a woman (Michael Pallandre, Adria Cordoncillo and Caroline Leroy), whose lifts and balances are enacted up close to the audience, giving everything an edgy feel. Perhaps because of our proximity, we really feel the relationship between earth and air in their work. Standing in a three-person column, they reach to the ceiling of the yurt, giant-like. Feet planted in spoil, head reaching to the sky. Tree branches, ropes and planks are brought into play – as is a creaking metal-framed hospital bed that comes hurtling into the space, and is the stage for a pretty distressing scene of puppet and puppeteer separation. This is a show about childhood, not a children’s show (the company programme advices 16+ although this isn’t upfront in the Fringe marketing) – although there are fair few young children in the audience, and they seem, on the surface anyway as there are no tearful exits, to be coping OK. Ah, the power of puppetry to tell harrowing tales in a safe way! There is also mask used – lovely carved round faces echoed in tiny sculptures placed in the soil.

The mix of puppetry and circus is an unusual one. It works, mostly – the skilled acrobatics playing out all the outer obstacles and inner worries of the child who is growing up in a violent world; the wooden boy puppeteered with tender care. The visual aesthetic of the piece is rough and earthy: Hessian, wood, unbleached calico, brown wool. And of course the soil, which by the end of the show covers the acrobats’ limbs.

I must also mention the live music – beautiful cello by Florence Sauveur. And my favourite moment from the show, when the acrobats carry her aloft, and she continues to play…

T1J (Theatre d’un Jour) are an established group, led by Patrick Masset – they’ve been going for 20 years and have played at festivals worldwide, including the acclaimed Festival d’Avignon. They seem to like eclectic mixes – their next show will apparently be a mix of opera and circus.

Although I don’t see L’Enfant Qui as a wholly successful show – I’d have liked the dramaturgy developed so that we didn’t need an explanation of what we were about to see – I applaud it wholeheartedly for its ambition merging of form.

L’Enfant Qui is shortlisted for a Total Theatre Award for Circus at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2014.