Crash! A body lands from a height – it’s a wake-up start to the show. The body belongs to a young woman who seems a little bit dazed but OK, shakes her head a few times, tumbles with ease across the small stage. Then – jerk! Some kind of synaptic snap occurs, and she’s thrown into confusion. Where is she? She remembers crossing the road, her mobile vibrating, it’s her brother and she doesn’t want to talk to him, she finds it hard to talk to him, she’s bought some socks for her dad because all the ones he has have holes in them, people say he drinks too much, she can see this guy Gill who she likes. Her first thought is: someone has screwed up; her second thought is, oh it’s me that’s screwed up; her third thought is, I don’t want Gill to see this…

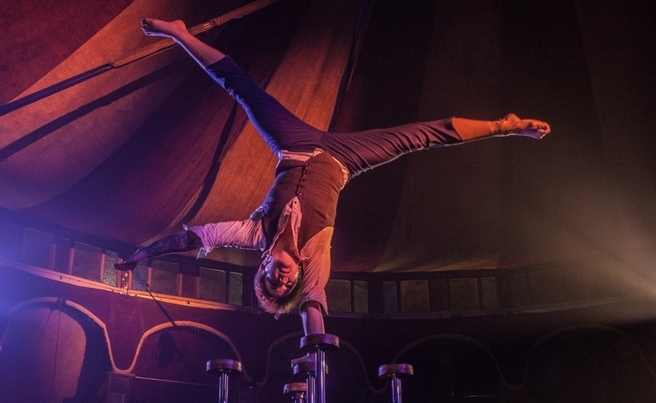

Jerk, presented by Australian circus company Casus, is a solo show performed by the extraordinary, awe-inspiring, ridiculously talented Emma Serjeant and expertly directed by British physical theatre luminary John Britton. Although in its early days as a show, it is already an outstanding piece of circus-theatre.

Creating good circus-theatre is an enormous challenge. How to weave narrative and circus skills together in a believable way? In particular, how to integrate circus equipment into that narrative? Jerk is a text-book example of how to get it right.

First, keep the narrative simple, poetic, a snapshot of one moment in time that explodes outwards into a world of possibilities – a short story rather than a novel. The story is not obscure – it becomes obvious pretty early on that our heroine has been the victim of a road accident – but where is she now? In recovery? In a coma? Facing the moment of death? It’s unclear – by which I mean unclear in a good way: there’s room here for the audience to be part of the creative process, to work at interpreting the story.

Rule two: use the intrinsic qualities of the circus equipment to aid the telling of the story. Aerial equipment offers the play on fear of falling and crashing, so fall and crash; hand-balancing equipment is wobbly, so wobble and twitch; tiny hoops can contain and trap the body, so are an excellent metaphor for a body trapped in a nightmare physical experience.

Next, find ways to use skills that you have in an innovative way at the service of the story. Emma Serjeant’s huge arsenal of circus skills includes a command of the speciality nail-up-the-nose trick – here re-invented with other objects in a flashback party scene of drug-taking and puking that simultaneously evokes a suggestion of hospital breathing tubes and feeders forced into a struggling body. Clever, so clever!

Last but not least, remember that the audience is part of the theatrical equation. Emma, in character as Grace – the smart and pretty girl who is a successful photographer and whose idea of rebellion is leaving the dishes overnight – draws us into her story through direct address from the stage, and later leaving the stage to take Polaroid photos that capture the moment, reinforcing the core ‘snapshot moment in time’ motif running through the show.

Text is used beautifully, sparingly in the show – a mix of recorded and live spoken word. A concealed radio mic picks up words, breath, the sound of contact with equipment, this all weaving in and around an evocative soundtrack that is always in service to the physical action. Lighting design uses straightforward archetypal colour-association to add to the storytelling (and there really is nothing wrong with being obvious in these matters) – blue is cold confusion, red is a dreamworld of past memories.

It is really hard to fault this show – it feels raw and fresh, and its brand-newness is visible, but that is fine by me. It will no doubt grow and change through performance, but I hope it doesn’t change too much. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. It runs for just under an hour and every moment feels vital, alive. As the show ends, I walk out into the Spiegelgarden, feeling like a rabbit caught in the headlights, dazzled by this extraordinary experience.

Casus’s previous show Knee Deep was shortlisted for a Total Theatre Award at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and currently (May 2014) is also presented at the Spiegeltent as part of the Brighton Fringe. Jerk is a radical departure for the company, a brave experiment that has paid off, and proof that circus and theatre can, in the right hands, combine to become a powerful force.