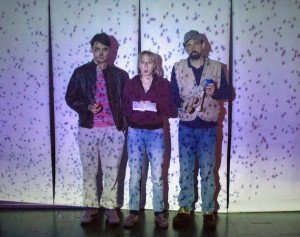

Our Dancing Feet at Oceana, Brighton. Photo Ray Gibson

Oh won’t you walk with me! Dorothy Max Prior reflects on recent promenade theatre work

West Street, Brighton on a chilly Saturday night in November. Reader beware, we are entering the brash and breezy land of street fighting, arcade gambling, and hen night shenanigans. Walking down this street is like entering a film set, or an impromptu street performance, where it is hard to believe that the scenes playing out haven’t been staged for our amusement. Here, a group of extremely drunk women in high heels and bunny ears stagger into the road, bringing traffic screeching to a halt. There, a pair of topless muscle-bound men in white tutus stride confidently along. Down we go, past the whizz-bang clamour of the one-armed bandits in the Regency Arcade and the smokers leaning against the peeling green-paint front of Molly Malones pub; the smell of take-away noodles, spilt beer, and vomit following us as we go; the sound of pounding rock, shrieking laughter, and breaking glass competing with the hooting of the cars that are trying to negotiate the sea of pedestrians veering into the road. St Paul’s church spire rises up in protest at the decadence and debauchery playing out all around it.

At the bottom of West Street, where it meets the blustery seafront, stands Oceana nightclub. Its capacity is two thousand plus, it is designed to look like an ocean liner, and it boasts a whole raft of differently themed spaces – the Tahiti Room, the Monte Carlo, the Boudoir, the New York Disco, the Reykjavik Icehouse. Visit the whole world in one night, as the publicity says. On this particular night, the venue is host to Our Dancing Feet, a multi-discipline site-responsive project from Zap Arts and Inroad Productions, featuring a cast of fifty professional and community performers and artists. The production includes a video mapping piece by Shared Space and Light, sited outdoors at the Clocktower, where the audience start their journey; an interactive installation piece by sound artist Thor McIntyre Burnie, sited in a bar at Oceania, linked by screen to a secret location inside the building, on which the audience can see a quartet of performers improvising to the audience’s instructions; and Our Dancing Feet itself, a promenade theatre piece that takes its audience on a journey through the venue’s many spaces.

Our Dancing Feet is based on a written script by Sara Clifford – a play, no less! In the hands of director Terry O’Donovan and the rest of the creative team, it is taken not from page to stage but from page to staircase, table, toilet, bar, dancefloor and corridor. Referencing the glory days of the Regent Dancehall, the audience are taken from the original site of the Regent (now a branch of Boots by the Clocktower in Brighton – where the video mapping piece is projected, reflecting on the site’s former life as a dancehall) down West Street (the site for street performances staged and unstaged) to Oceania, and are then led through the labyrinth that is this modern nightclub – hopefully appreciating the contrast between the setting of the play (1953, on the eve of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation) and the slightly tawdry bling and pizzazz of this contemporary successor to the dancehalls of yore.

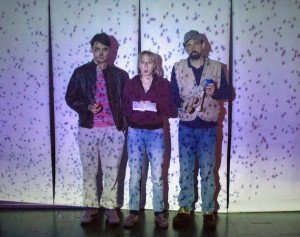

Our Dancing Feet, West Street, Brighton. Photo Ray Gibson

As one of the creative team involved in the production – and thus needing to get myself into place before the arrival of one of the split groups of audience members, or to usher community performers from one scene to the next down hidden staircases – my experience of the show is by necessity a fragmented one. Most of the time I feel like a rather large and clunky mouse, taking off my clippy-cloppy dance shoes so I can creep along a corridor below a scene on a staircase, not only unseen but also unheard. Ah, yes moving around unheard – there’s the rub. At the beginning of the show, I need to take a group of twenty young performers from their slot doing small street theatre vignettes on aformentioned West Street into the building and downstairs for their first scene in the Disco. During the dress rehearsal, they understand the not-being-seen part of the process, but as soon as they are out of sight of the audience, the whispering and throat-clearing starts – and as we head down the hidden staircase at the back of the building, the shoes clomp merrily down… Lesson number one in promenade performance: how to get around the building not only wearing an invisibility cloak but also silent as the night. By opening night, they’ve got it – quiet as mice.

I remember years ago interviewing Punchdrunk when they had just made Faust and were about to start work on The Masque of the Red Death. What’s the first thing you’ll do? I ask. ‘Play hide-and-seek throughout the building, in the dark’ says director Felix Barrett. Punchdrunk are current leaders of the promenade pack, having made their reputation on large-scale site-responsive performance. They’ve previously worked in many different ways: in outdoor and indoor performance; in street arts and in collaboration with the ENO; and in their site-responsive promenade work have played with small-scale intimate work like The Yellow Wallpaper through to their famous large-scale extravaganzas such as current success The Drowned Man. The format that they’ve used for many of their best-known works is to create an environment through which the audience promenade at their own pace, choosing to be diverted by performance scenes, or to loiter in empty rooms or corridors, investigating the installation pieces created in each space. Audience members are issued with masks which they are instructed to wear at all times – the troupe of masked people being thus distinguishable from the actor-dancers, but also becoming part of the scene – like a group of ghosts observing the action. The masks theoretically stop people nattering to friends, taking on board that they are part of a mise-en-scene, although that isn’t always the case. Punchdrunk’s work creates a setting where the ‘promenade’ is of the audience’s own choosing. There are always many different possibilities: to stay and witness a scene or to walk away in search of the next one; to move away from the action into the quieter corners, or to hot-tail after a chosen character to see where their journey takes us. Not only is the narrative fragmented, but it is also not deemed necessary to piece it all together. Two or three friends going their separate ways will find at the end of a show that their journeys have been radically different. For many people, this is a huge part of the appeal – the ‘Oh but didn’t you go through the fireplace into the hidden room?’ syndrome. Further to this, Punchdrunk often set up secondary performances within the show, to be discovered by some but not all audience members; or create real-life gaming challenges in which solutions to quests are informed by interaction with a linked website. For these and all sorts of other reasons, Punchdrunk’s work has broken out of the theatre ghetto and into the mainstream, bringing the notion of site-responsive and promenade performance into the public consciousness.

Dreamthinkspeak – Before I Sleep

Meanwhile, back at the arthouse, dreamthinkspeak have set up a contrasting example of the promenade form. Although they have experimented with other ways and means, their most commonly-used format is for a character (or characters) to welcome the audience into an opening scene, then to set the audience loose without a human guide, but for the space and the route through it to be very carefully orchestrated and manipulated – with sound and light playing a key part in drawing audiences through the space. In works like Don’t Look Back, Underground and Before I Sleep, we find ourselves drawn deeper in and further down by the sound of a violin playing around the corner, a muttering of voices, or a flickering of lights. Often we encounter performers behind glass, or in dark corners, or speeding past us at a distance. The notion of the remains, the trace, the echo of human action is a common motif in dreamthinkspeak’s work: the half-eaten feast, the slammed door, the receding footsteps, the toys abandoned mid-game. Often, film is used to give further layering and echoing. We see characters that we’ve glimpsed in the distance in close up; or we see filmed scenes that inform scenes we’ve witnessed live. Dreamthinkspeak have mastered the art of audience manipulation (in the best sense of that word). We find our way through the site, loitering at will, yet never feeling hurried – and we get a complete experience, the whole performance text, so to speak.

Promenade performance – partly due to the success of Punchdrunk, dreamthinkspeak, and other companies – has become increasingly popular over recent years. Why? No doubt there are many reasons, but surely one must be that with sitting down to focus on screens (computer, smartphone, tablet, game console, TV) taking up so much of our time, when we go out to play at the theatre, we don’t necessarily want or need to be sat on our behinds to be entertained…

Although we sometimes view the promenade theatre form as something fairly recent, those of us who’ve been around a while are aware that it has been steadily growing for decades. Pioneers of the form in the UK, such as The People Show and Geraldine Pilgrim, are still going strong. Geraldine Pilgrim’s most recent work is TOYNBEE. As Beccy Smith says in the opening to her Total Theatre review of the show: ‘Geraldine Pilgrim has been creating site-responsive performances and installations since long before Punchdrunk ever donned a mask or dreamthinkspeak first re-cast classic text into architectural form.’

Geraldine Pilgrim has previously made work in a many different extraordinary sites, from empty hotels to disused swimming baths and abandoned cigarette factories. In 2013, she was commissioned to create a work for Toynbee Studios, exploring the history of this philanthropic organisation and long-standing centre for arts, education and the promotion of social welfare. How to get the audience through the space is the biggest challenge of promenade performance, and in TOYNBEE a mix of modus operandi are used. At some points on the journey, ushers welcome us in or out of rooms. As the show progresses, each audience group is assigned a character from the show who appears at various crucial moments as that particular group’s guide, acting as a kind of liaison between audience, performers and space.

In Our Dancing Feet, a key element of the text of the play provides a natural solution to the problem of moving the audience around, at least for the first section of the show: there is a narrator character (Joan) looking back on her youth, and encountering her younger self (Joanie) – so it is an obvious and easy decision to have Joan draw the audience into her world and lead them through the space, encountering aspects of her earlier life brought to life by her memory. This device is used for the first 20 minutes of the production. When the audience arrive, they are discretely divided into groups and led off from a bar at staggered times, weaving through corridors and bars, meeting a bevy of characters who tell their dancehall stories through monologue, dialogue, visual tableaux, dance, or physical action. Through a frosted window we see a young women waltzing in slow motion on a tabletop. Beyond a glass door, a man in a glittering tuxedo dances a deconstructed mambo. Weaving through a crowded corridor comes a young man in an elegant suit, marking out a quickstep. Later in the production, the audience groups are brought together and one section of the audience encounters another group enjoying a dance class. The audience are later led by the voices of the main characters through a maze of corridors, toilets and back alleys in the darker recesses of the club, to then enter the main ‘ballroom’ enticed by a blaze of lights and the sound of jazz played by a live band. From here on in, the action moves around the enormous main space of Oceania, sometimes ‘onstage’ – that is, on the dancefloor – and sometimes by the bar, on the bandstand, or at the DJ booth. The audience are free to sit and stand where they like, and to move freely around to gain a new viewing point. In this final section of the show, the audience are ‘led’ from scene to scene by the shifts in location of the actors, helped by a sound and lighting design that moves the attention to the relevant place in this cavernous space.

Dante or Die – I Do

When we think of promenade work, we often imagine this type of larger-scale work, leading an audience through a labyrinth of spaces, and negotiating the demands of a big site – but the form also lends itself to more intimate encounters. Terry O’Donovan, director of Our Dancing Feet, is also founder/co-director of Dante or Die, whose promenade show I Do is soon (February–March 2014) will return to the Almeida in London, where it premiered in July 2013. Or at least, the show is presented by Almeida – it is actually sited in a hotel, and tells six different interwoven stories about the dawn of a wedding day, viewed in six different hotel bedrooms. It’s a very cleverly managed piece of work. The six scenes could be thought of six short stories in one volume. Each is intertextual with the other; each fills in gaps of knowledge that arise in other stories. Yet each is its own complete tale told well, presenting the perspective on the day of one character or group of characters. Thus we meet (the order depending on what wedding usher we are assigned to): the neurotic mother of the bride; a very nervous best man (O’Donovan himself, on brilliant comic form); the hilariously hung-over bride and bridesmaids; an angst-ridden groom having second thoughts; the elderly grandparents tussling with the complications of wheelchairs and easing stroke-bound limbs into dress shirts; and the Matron of Honour behaving not so honourably in a secret tryst in the bridal bedroom. Because each story is complete in itself, they can be presented in any order – and it is a sign of how well the show works that everyone who sees it is convinced that the order of scenes they witnessed is the right one! The stories are not only told concurrently, but are intended to be viewed as happening in the same 15-minute time-slot. So as we leave each room, we encounter a hotel chambermaid cleaning the corridors, and then see her moving back in time – iPod playing her music backwards as she reverses down the hall. A very clever note! I Do is now in its second successful year – I saw it in October 2013 in a hotel in Reading as part of the Sitelines Festival, an annual event dedicated to off-site and site-responsive performance work.

Touched Theatre – Blue

Also on the smaller scale is Touched Theatre’s Blue, which is a promenade piece staged in a succession of small rooms (these could perhaps be the smaller spaces and out-of-bounds areas of a theatre). At the Suspense Festival (London, November 2013), the work is presented in a series of usually unused basement spaces. Reflecting on Blue gives an opportunity to flag up that although much promenade work is specific to a certain site, it is the ‘promenade’ aspect that is the key element in Blue, not the specificity of the site. The show is adapted to each site but unlike, say, I Do (which needs to be set in a hotel) or Our Dancing Feet (which needs to be sited in a dancehall or nightclub) – Blue can be performed in any succession of small rooms. The content of the piece is distinct to the site: within the show, there is the construct that we are in a bar, or a fisherman’s cottage by the sea, or in someone’s kitchen. In this sense, the piece is closer to conventionally staged theatre in that we suspend disbelief about our surroundings and allow ourselves to be taken someplace else. Why then make it as a promenade piece? It’s a show about displacement, about being ‘lost’ and the constant upping and moving of the audience creates an ambience of actual transition that echoes the perceived experience of the absent main character – a missing girl. Ultimately, the show is less about her than it is about the people she leaves behind – which of course is always the case when someone is gone to us. They remain as an echo, a series of memories, an impression – there is no knowing what they actually think or feel themselves, or even if they are still able to think and feel. On a practical note, the audience is moved through the space by the characters, with elements of puppetry, film and sound (with an ingenious device of the soundscape emanating from a series of little boxes set up in each room) adding crucial extra layers of imagery and resonance to the text of the piece. Touched will be re-touring Blue in autumn 2014.

Meanwhile, Our Dancing Feet dances on – the second phase of the project is now (February 2014) in process, at the Winter Garden in Eastbourne. It’s a very different venue to Oceana – instead of a contemporary nightclub we have a splendid old building with a long history, replete with not one but two functioning ballrooms, a gilded and flock-wallpapered foyer, and numerous adjoining rooms, corridors and staircases – how the show gets reworked into this space is yet to be seen, and what the audience’s journey will be is yet to be discovered…

Our Dancing Feet was performed at Oceana, Brighton on 15, 16 & 17 November 2013. Written and conceived by Sara Clifford, directed by Terry O’Donovan, designed by Lucy Bradridge, choreography by Dorothy Max Prior. Produced by Veronica Stephens for Zap Art and Sara Clifford for Inroads Productions, in partnership with The Ragroof Players, Shared Space and Light, and Thor McIntyre Burnie. Additional street performances on West Street Brighton by performing arts students from City College, Brighton. Our Dancing Feet next plays at The Winter Garden Eastbourne on Saturday 22 March 7.30pm and Sunday 23 March 1pm & 6pm. The show is free but ticketed. To book please call the Box Office on 01323 412000 or email boxoffice@eastbourne.gov.uk. See the project website here.

Dante or Die’s I Do will be performed 26 Feb – 9 March at Hilton Docklands Riverside Hotel, tickets via www.almeida.co.uk

For more on Touched Theatre’s tour of Blue, and the opening of their latest show, Faust [redacted], a new adaptation of Dr Faustus, presented at the Little Angel Theatre 16 & 17 March 2014, see the company website.

Punchdrunk’s The Drowned Man: a Hollywood Fable, supported by the National Theatre, continues its London run until 6 April 2014. For dates and to purchase tickets, see here. For more about the company, visit www.punchdrunk.com

For more on dreamthinkspeak, visit the company’s website.

For information on Geraldine Pilgrim’s TOYNBEE and other work, see here.