Pain, humiliation, pressure, panic… Kunal M Rajput enters the world of Dark Clown, courtesy of the legendary Peta Lily, and lives to tell the tale.

Few encounters in an artist’s life truly unsettle the ground beneath their practice, but Peta Lily’s Dark Clown did so for me. I attended Dark Clown – An Experiential Talk at the first Bouffon Festival in London in October 2025, where Lily delivered a performance-lecture of remarkable precision and intellectual depth. What struck me first was her command of the room, a performer guiding an audience with the charm of her performance and the sensitivity of a teacher. The experience was unlike any session-performance I had attended. It was not only that the aesthetic reached for darker tonalities within the clowning palette. It was that the event forced a reconsideration of what theatre asks of its audiences, what it demands of performers, and how actor training equips practitioners to meet both craft and conscience.

Lily trained with master teachers including Jacques Lecoq, Philippe Gaulier, and Monika Pagneaux, amongst others, and she has spent decades practising the craft, performing and training performers around the world whilst refining what, since its inception in the early 1980s, she has called Dark Clown. Her care with language is striking. She reminded the audience that her form is not violent-clown or horror-clown but an extension of clowning’s expressive range and dramaturgical possibilities. Dark Clown draws on the technical foundations of red-nose clowning such as rhythm, elasticity, and timing, yet it relocates the clown into situations specifically designed to release what she calls ‘Marginalised Emotions’ such as pain, humiliation, pressure, panic, oppression etc. The laughter that emerges is not simple release. It is what she calls ‘Troubled Laughter’, a tightening of breath that blends relief with a sense of shame. Imagine actors in the near-death scene of the movie Final Destination being able to make the audience laugh at their life-or-death moment.

The origin of the form illustrates its philosophy. In 1980 at the ICA, Lily watched a scene in a show in which a prisoner was compelled to perform for his captors within a totalitarian regime. He sang, moved, and struck his head with a metal tray. The scene was both grotesque and absurd. The audience laughed, although they sensed they should not. Lily mentions that she felt a sharp sensation in her body in that moment of laughter, which she later named ‘troubled laughter’. This physiological detail is not anecdotal alone. Neuroscience suggests that spectators mirror rhythm and breath, meaning theatre’s impact is not limited to thought but resonates through the body. Bertolt Brecht’s Verfremdung or alienation effect sought to unsettle audience’s thought, whereas Dark Clown unsettles audience’s breath. The performer becomes a conductor of audience physiology: coaxing, pressing, and releasing. In doing so, they implicate the audience. Spectators feel complicit in what unfolds and understand, at a visceral level, the moral stakes.

This, I believe, is the political potency of the practice: not argument delivered through rhetoric, but argument felt through the body.

Some young actors may initially perceive Dark Clown as ethically uncertain or harsh, but Lily avoids anything gratuitous. She begins sessions with content notes and wellbeing guidance, emphasising that Dark Clown is a disciplined craft rather than a pursuit of shock. She distances it from horror tropes and cynical clowning. Instead, it opens a path toward emotions that often sit at the margins: distress, shame, panic, humiliation, dread, and existential unease. Safety remains central. The actor does not need to rely on personal trauma. Imagination and craft carry the work.

Lily’s methodology is pragmatic and specific. One strand focuses on comic technique, such as motif, rhythm, and contrast, which are rooted in red-nose clowning. Another strand trains performers to inhabit impossible circumstances with conviction. The final strand demands the capacity to calibrate and respond to an audience in real time. This structure offers actors significant advantages: it allows them to explore intensity and extremity without mining personal trauma. Instead, it encourages imaginative commitment rather than self-exposure, while still maintaining the inner sense of play of the red-nose clown.

A crucial requirement of the form is believable suffering. Dark Clown relies on audiences accepting the reality of distress or pressure: if the portrayal seems false or indulgent, the implicating effect collapses. Lily contrasts her practice with shock-based performance, which often centres on the performer’s thrill. Dark Clown is not built on transgression. It is built on calibration. She cites a circus scene where a small clown receives repeated electric shocks while a larger clown controls the dial. The audience laughs even as the discomfort grows, and the guilt that follows sharpens rather than erases the humour. This tension is not a desire for cruelty. It is a deliberate dramaturgical device that prompts spectators to question their visceral reactions.

I believe this implicating effect is political at its core. Political theatre is often expected to present arguments to be effective, yet Dark Clown shows that political insight can emerge through physical sensation. A tightening of the diaphragm, a flicker of guilt, an altered breath: these physiological responses create a different cognitive terrain. A room that laughs with unease becomes alert, unsettled, and no longer a passive witness. This shift echoes one of theatre’s oldest functions: the transformation of human consciousness. Here the transformation arises from discomfort, and Dark Clown offers a contemporary way of producing that cathartic shift. It brings shame, horror, and release into an interplay that shapes the audience’s moral sense, all through the implicating effect at the heart of the practice.

The form is also rich for actor training. Many drama schools now treat emotional vocabulary in training as too subjective or risky, but Dark Clown provides a structured mechanism for actors to engage rigorously with difficult feeling-states. Dark Clowning exercises such as competitive crying rituals, guilt-based panels, or prisoner-games are not sensational tricks. They serve as rehearsal grounds for ethical decision-making and for sustaining extreme contradiction while holding an audience’s attention. They prioritise the performer’s wellbeing while extending their expressive range.

Dark Clown is, above all, a craft of attention. It refines rhythm and escalation, teaching actors how to intensify moments without slipping into melodrama. It also sharpens the ability to sense and respond to an audience’s breath, encouraging performers to maintain an internal clown even within naturalistic work, keeping spontaneity alive. These skills are transferable, allowing performers to escalate tension without excess, implicate without exploiting, and make an audience feel the moral cost of laughter in problematic contexts. In this sense, Dark Clown teaches play and stakes within dramaturgy as much as comic technique for an actor.

If theatre hopes to poke and provoke us, Dark Clown is clearly one of the important instruments. It brings discipline to discomfort and responsibility to provocation. It guides audiences toward uncomfortable truths without abandoning care for the performer. Troubled laughter becomes a mirror that reflects complicity and empathy at once. At a time when performance often feels cautious or overly cerebral, Dark Clown brings feeling back to the centre of craft and restores theatre’s essential promise: to unsettle, to move, and, when the moment is right, to implicate us.

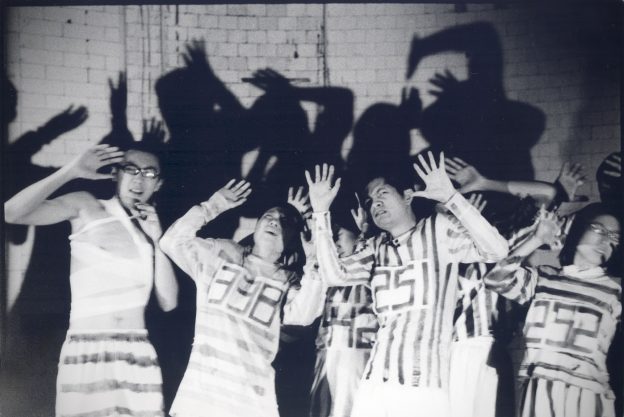

Featured image (top): Hamlet or Die, devised and directed by Peta Lily for Hong Kong Mime Lab 2000. Photo Esvigo.

For more on Peta Lily’s work, see www.petalily.com

For her blog on Dark Clown see here.

You can follow her @petalily on Instagram and Facebook.

Kunal Rajput attended Peta Lily: Dark Clown – An Experiential Talk at the world’s first Bouffon Festival at The Pen Theatre, London, 16 October 2025.

Kunal Rajput took part in Peta Lily’s Clown and Dark Clown Workshop in August 2021.