Forced Entertainment’s latest theatre piece plunges us into a whirling world of mock-magic as we witness three performers perpetually failing at a mind-reading feat. Real Magic, premiering at the Attenborough Centre of Creative Arts (ACCA) in Brighton, sees two of Forced Entertainment’s founder members, Richard Lowdon and Claire Marshall, joined by Jerry Killick, who has worked with the group on numerous earlier shows including Bloody Mess and And on the Thousandth Night, the latter also being presented in the same week at the ACCA.

The three performers are dressed in bright yellow chicken outfits, and the show purports to be part mind-reading feat, part cabaret act, and part chaotic game show. One acts as presenter, one as contestant, the third is the ‘thinker’. ‘So, the way it’s going to work is this – think of a word,’ says one fluffy yellow chicken to another. ‘Richard is thinking of word. What word is Richard thinking of, Claire?’ The third holds a large piece of cardboard to the audience with a word written large on it. Caravan. Algebra. Sausage. ‘Is the word Hole, Richard? No, the word’s not hole, Claire’. Second and third guesses are permitted: ‘Money?’ Electricity?. Inevitably, the correct words are never guessed, the same few incorrect answers are always given. There is struggle and comical repetition. Roles are swapped.

After some time, our three protagonists become bored. How to keep going? Why keep going? Is Jerry feeling good? Is Jerry feeling confident? They are trying to be nice, to keep it all going, to be part of the party. Optimism – a consensual conspiracy to keep going. There is count-down ticking. There is canned laughter. Chicken costumes become half on and half off. They are down to their underwear. A glittery gold dress is hauled on. A suit and shaggy wig is brought into play. It’s vividly monotonous, yet varied, constantly evolving – recycling in a mutated way. It is gentle in its audaciousness. We want them to be a winner for us. We laugh at Jerry’s enactment of Rodin’s The Thinker, thinking so hard. Jerry is thinking all over Richard, yet Richard just does not get it. I reflect on how sometimes the answer to our predicament is right in front of us, and we just cannot see it. We try to do our best, try to play the game, to help each other, to be part of something, yet fail and fail again and become more and more exhausted, finding and clinging to little strategies to keep going. When words, interactions and guesses fail, a strategy they have is resorting to ‘the dance’, with which to bide time. The dance is done in a row, dressed in the fluffy yellow chicken costumes.

Real Magic is a super-brutal machine that is inescapable, the rules of which cannot be changed. We are gripped by the chaos and earnestness, witnessing constant attempts and resilience, time and time again, variations within a theme. It’s daft, it’s relentless. A game of expectation and anticipation. A constellation of tensions that become shifting forces within the moment. We see different roles we play in life, the varying balances and interplay we have with each other. The different costumes that we put on. Even if they did get the answer correct, what would they win? There are no prizes to be won. Is there a hope they would be better off? More valued? Celebrated? Why don’t we, the audience, call out the correct answer? It is written right there on the card in front of us. Why does it keep our interest? We want to witness a winner? We ‘enjoy’ the awkwardness? We know it is just a game? The audience are riveted. The audience are smiling, complicit to this game of never getting it right, more and more reckless. We believe in them, and somehow invest in them. Even with help, they still get it wrong. Perpetually starting again. We believe in their belief. The three players are a set of individuals who somehow thrive, and find their way, within a structure that they cannot change. The event exists as a real event that is unfolding. There is a fierceness, breaks and twists and turns, and plays of language and words, solutions and gifts coming from the interplays. Irreconcilable differences.

It becomes an emotional journey, watching this show. It opens up stories within your own life. Repeat and repeat again. Each day we start and end and go through sets of actions and interactions in our various roles. Can anything really be changed? We are enchanted, we are bothered, our attention shifts and drifts away, we make connections and disconnections, we zoom in and out of focus, we laugh, we squirm, we reflect on something about our own lives and attitudes, will we ‘get it right’ this time? Even if the answer is staring us in the face? Arrive at a particular point? Gain something? Be better, be wiser, be richer, be more loved? We are surprised, riveted and somehow delighted. Futile attempts and fade in memory and hope teases us. We live, and we live with limits…

Director Tim Etchells, in the post-show Q & A, says that the first third of Real Magic is a reconstruction of the feeling – how it all felt, to be making & improvising this work. Like other Forced Entertainment shows, Real Magic although appearing so in the moment, is not improvised, It is very tightly scripted/choreographed, and there are targets to hit to make it work.

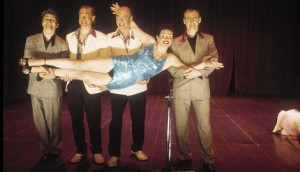

Forced Entertainment: Showtime. Photo Hugo Glendinning

Real Magic is another in the long, ongoing series of Forced Entertainment shows that uses the tropes of ‘variety’ ‘showbusiness’ and ‘theatricality’ – former examples include Showtime (1996), First Night (2001), Spectacular (2008), and The Thrill of It All (2010).

I have seen many of their shows and installations/artworks, from the brilliant Speak Bitterness of 1994 onwards, and I notice in all Forced Entertainment’s work the examination of the delicacy of life, the exploration of the interplay of the individual with other people and forces – connections, disconnections, twists, turns. Cycles and repetitions. Having hope, yet optimism being stunted. Living, acting, and operating within a system – and always the question of how much agency we really have. Forced Entertainment make performances that excite, question, challenge, and entertain their audience, with a penchant for confusion as well as laughter. The company explore what theatre and performance can mean in contemporary life , in a continuing process of conversation and negotiation.

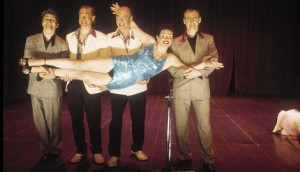

Forced Entertainment: And on the Thousandth Night.

Photo Hugo Glendinning

And on the Thousandth Night is an older piece, created in 2000 for Festival Ayloul in Beirut, drawing on one section from Forced Entertainment’s epic twenty-four hour performance Who Can Sing A Song to Unfrighten Me? (1999). Taking its title and part of its inspiration from One Thousand and One Nights, And on… is presented at ACCA as a 6-hour durational work, exploring the live relationship between a story and its public, and between a story and its tellers.

As the audience enter, the eight performers – all six founder members of Forced Entertainment, including director Tim Etchells, plus Jerry Killick and Nicki Hobday – are ambling about the stage, like pre-match boxers, each wrapped up in a simple red swathe of fabric that represents a regal cloak. Each wears a cardboard crown. As the audience settles, each performer takes a chair and they form an orderly line downstage, directly facing the audience. (This line of chairs downstage is another Forced Ents trope, repeated in many shows.)

And so it starts. Once upon a time there was a king, who had three daughters… Stop – the narrative is interrupted. Once upon a time there was a queen with six sons… Stop. Once upon a time there was a speck of dust, floating in a room, for years… They each listen intently to each other as a story is begun, then cut short, the moment being taken to change course. Some performers retreat upstage to take refreshment, but stay involved through their intent listening. Sometimes a story is extraordinary. Another one is just daft, another familiar, another horrific, another banal. Sometimes the narrative rises up very quickly, and then is done with swiftly: Once upon a time there was a shadow that had nothing to attach itself to.

Can the eight performers deliver every time? Will they run out of story? Be interrupted just at a crucial point of the tale? Stay energised? Remain articulate? The work feeds on folk and fairy stories, news events, and personal experiences. Tales help us better understand the way of the world that we live in, yet we can never get to the end, nor arrive at a conclusion. I stayed for the full six hours, wondering how something that wouldn’t permit an ending, would end. In fact, the six hours ends quite beautifully, like a steam train slowing down and arriving back into its station. Once upon a time there was a heart that did not stop beating. Once upon a time there was an ear that did not stop listening. Once upon a time there was an eye that did not stop looking. Once upon a time there was a pulse that did not stop pulsing. Once upon a time there was a brain that did not stop thinking. Stop. The eight storytellers leave the stage, leaving behind their red capes and crowns, draped and disowned upon their chairs.

The performance is about absent things that you summon into the space. An audience coming together is a place of measuring. And on… works with a Music Hall-style direct address to the audience – and all the performers are all the time are listening to the story being told, their response seemingly making or breaking that story. The nature of storytelling, and an exploration of how we tell stories, is an ongoing line of research for Forced Entertainment, manifesting in very many different ways – from the stripped-down minimalism of The Travels to the exuberant organised chaos of The World in Pictures.

Seeing this classic show from the FE repertoire alongside the company’s latest work, Real Magic, is interesting. They are very different works, but it is easy to draw parallels; to see a continuum in their work. Both are performed direct to audience, have similarities in form, a sense of play, being ‘in the moment’ of creating and breaking, using kitsch theatrical dressing-up costumes and cardboard. Both inspire feelings of being challenged; provoking questions, causing confusion alongside delight and wonder. Both leave you with a feeling of having been entertained and moved. Both share emotional landscapes that never ever resolve. Most crucially, both fulfil the company’s aim of creating work that is ‘something that needs to be live’. Haunting, enticing, surprising, as ever, Forced Entertainment proves to be a curious joy and a magical gift.

Forced Entertainment: First Night. Photo Hugo Glendinning

Forced Entertainment started working together in 1984. They are an ensemble of six actor-creators: Robin Arthur, Tim Etchells (artistic director), Richard Lowdon (designer), Claire Marshall, Cathy Naden, and Terry O’Connor. Their work embraces theatre, performance, gallery installations, site-specific pieces, books, photographic collaborations, and videos.

They are based in Sheffield, and tour worldwide. www.forcedentertainment.com

Forced Entertainment: Real Magic premiered at the Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts (ACCA) 10 & 11 November 2016. Miriam King attended on Friday 11 November.

And on the Thousandth Night, a durational performance, was presented on 12 November, 4pm to 10pm.

As part of the Forced Entertainment residency, the ACCA programme also included a talk with Forced Entertainment’s artistic director Tim Etchells and Dr Sara Jane Bailes of the University of Sussex (12 November 2016), and a screening of Uncertain Fragments, a video essay by Hugo Glendinning and Tim Etchells about the company’s work, focused around the creation of their 2001 show First Night.

www.attenboroughcentre.com

Featured image (top): Forced Entertainment: Real Magic. This and all other photos are by longterm Forced Entertainment collaborator Hugo Glendinning.

www.hugoglendinning.com