January Blues? Not in New York says Terry O’Donovan, who is there to report on a flurry of festivals…

It’s January. The temperature is well below freezing, but that hasn’t stopped the international theatre-world from descending upon New York for a myriad of theatrical festivals, conferences and symposiums. Armed with a furry hat, leather gloves and a giant scarf I spent the first ten days of the year pounding the streets of Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens, dodging the discarded Christmas trees to see what the city’s festivals have to offer. COIL Festival, Under The Radar, Prototype – where to start?

COIL Festival, in its 10th year is a benchmark for the experimental company and performance makers, spanning dance, improvisation and installation-performance; curated by PS122’s artistic director Vallejo Gantner. The TEAM, who regularly perform their unique brand of Americana on UK soil (former Total Theatre Award winners for Architecting), have revisited their 2012 show, RoosevElvis, for COIL 2015 at the Vineyard Theatre. It’s a charmingly painful show, with as many laughs as moments of bittersweet tenderness. Annie, a reclusive meat factory worker, played with tender restraint by Libby King, spends her time speaking to Elvis at home whilst drinking bottles of Bud. After a disastrous road-trip with potential lover Brenda (Kristen Sieh), she sets out on a quest to get herself to Graceland, during which time she is ‘joined’ by Franklin D Roosevelt (played by Sieh) and Elvis (played by King). The story, about this painfully shy woman, is small and gentle, but exists within a landscape of huge American ideologies. It questions how the American dream functions in 2015 for those people who feel dwarfed by those who do succeed. The performances are utterly joyous to watch, with both women’s physicality and vocals utterly riveting, hilarious and heartbreaking. Slick set design coupled with outstanding film work helps to create an arresting performance that is a challenging, intelligent yet accessible.

A few blocks south, in an imposing church in the East Village called Danspace, Faye Driscoll invites us to take off our shoes and get cosy with her cast in Thank You for Coming. Some people get very cosy as her charming quintet of dancers entwine themselves amongst us, limbs getting into all sorts of orifices. One woman’s scarf ends up playing a role, someone else helps undress the men and pass them new items of costume. Thank You for Coming certainly makes you smile. The piece has three distinctive acts. The first, which takes place on a raised platform in the centre of the space sees the dancers desperately trying to stay connected to each other, whilst balancing in different positions, reaching out to audience members to hold onto. The second sees the ensemble perform a variety of scenarios through impressive and funny staccato movements. There are kisses and hugs, loves lost and won, rivalries, a slap on the face and the joy of human touch. Part silent-film, part wind-up toy, and performed to a soundtrack of our names being sung by Michael Kiley riffing on guitar, the sequence is unique and memorable. The cast chant our names, rejoicing in the mundanity of our lovely little lives. It’s a hopeful, celebratory piece that would make the hardest of hearts smile. The culmination of its three acts sees the company slowly create a huge collective experience with more than half the audience skipping together, revelling in a stage full of people of all shapes and sizes.

The Blind Date Project is more incongruous within the COIL programme. Within a festival of cutting-edge dance, performance and installation, it feels like a stand-up comedy piece that would be more at home at as part of a comedy-improv framework. Arriving in the back room of Parkside Lounge – a dimly lit, rough-and-ready downtown bar – we are invited to watch a blind date between Australian performer Bojana Novakovic and a different actor every night. Actress Larisa Oleynik was onhand to belt out karaoke and awkwardly make conversation with Novakovic on the night I was there. Although an interesting set-up, the piece lacks a drive that sets it apart from a vaguely amusing cringy first date. Unlike Tim Crouch’s An Oak Tree, which also employs the use of a different actor for each performance, the inclusion of this new actor is never pushed beyond the gimmick. I longed for the piece to give us deeper insight into blind dates and the modern culture of Internet dating.

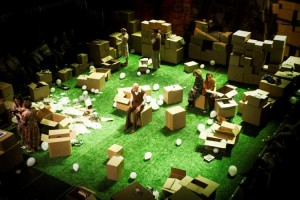

Under The Radar Festival has an impressively international programme, with work from Iran, Spain, Argentina, UK, Switzerland as well as homegrown talent. At another East Village performance institution, La Mama, Brazilian Compania Hiato’s O Jardim is a beautifully tender piece of work, which cleverly explores the futility of trying to frame our memories in order to remember them. A towering wall of cardboard boxes provides the backdrop for three generations of the same family’s story to be played out. Seated on three sides, each audience bank see each scene, whilst the other two are being performed to their respective groups. We hear echoes of the other scenes, but try desperately to focus on our specific scene, reading the Portuguese surtitles above the opposite bank of seats. Compania Hiato expertly use form to heighten the futility of the human need to connect and conclude. There are no easy answers, it is impossible to know what road a family’s trajectory will take, yet we are all drawn back to those things that connect us: a family garden (the title of the play), a tape left by your mother, a jumper that was given to you by your wife on the day you separated forever. We desperately try to connect these things, make sense of it all, in order to make sense of ourselves. What Compania Hiato creates wonderfully in O Jardim is a perfectly choreographed mess of a world in which we are desperately putting together the pieces. Performed with gut-wrenching precision and energy, the play is a revelation.

Under The Radar is curated by a team at The Public Theatre, a fascinating organisation that’s not afraid to mix Shakespeare with musicals and experimental performance. It plays host to director Daniel Fish who performs a new version of his 2012 production of A (Radically Condensed and Expanded) Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, which initially started life in Queens at The Chocolate Factory. The celebrated New York theatre director has taken recordings of the late David Foster-Wallace reading excerpts from some of his revered works, such as Consider the Lobster, Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, and A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, and from this has created a thoughtful piece with strong echoes of Forced Entertainment. Within a sea of tennis balls, four performers listen to Foster-Wallace’s voice through headphones and recount what they hear. Fish controls who hears what and when, so that at each performance the cast do not know exactly what pieces of text they will perform, or at what speed. This premise is an interesting way to try to achieve Fish’s objective of being utterly honest to the text so that the cast do not have any time to think about ‘acting’. In reality, it creates quite an odd performance style that can be frustrating rather than illuminating. When the only male performer, John Amir, races to keep up with the voice coming through his headphones he is obliged to speak so fast we have no chance to understand his frenzied utterings. When the text has room to breathe we’re allowed into Foster-Wallace’s wonderfully wry musings on cruise ships and a tennis player’s inane autobiography. The closing moments are the most poignant. A warm glow emanates from the pile of tennis balls as a performer voices the words of the writer’s widow, gently describing what he was like and how she will remember him.

Elsewhere in the city is Prototype, a festival for new opera-theatre and music-theatre, now in its third year. At St Ann’s Warehouse across the bridge in trendy cocktail-bar mecca Brooklyn, Carmina Slovenica (who are, unsurprisingly, from Slovenian) channel Samuel Beckett and Pina Bausch in Toxic Psalms: a dark vocal-choral performance that evokes concentration camps, unnerving violence towards women and human brutality. Performed by thirty-one young women dressed in decadent black gowns, the piece is littered with stunning images and incredible vocal harmonies. The chorus sings Eastern European medieval song as well as contemporary compositions, sometimes evocatively whispering them and at others shrieking with shrill cries evoking pain and fury. Using regimented gestural language throughout, the piece has a tendency to remain on one level and never quite emotionally moved me, despite its beauty. When the stage is littered in bright lemons and a sole woman arrives in a yellow dress it is a welcome jolt. Exquisitely lit by Andrej Hajdinjak, Toxic Psalms is a fascinating theatrical experience that continues to haunt long after the event.

These pieces are just for starters – you could see four shows a day and still not manage to catch everything. I didn’t even have the chance to catch companies such as Ockham’s Razor and Cirkus Cirkor at the Circus Now Festival. During my red eye back to Blighty, Taylor Mac is presenting A 24 Decade History with Under the Radar. The edibly brilliant performer is mashing up pop music from three decades, and the piece will eventually by 24 hours long – an hour for each decade. Let’s hope that version arrives on UK soil at some stage.

For now, I’m certainly in a New York State of mind. The festivals play host to a range of edgy performances that seem to be asking New Yorkers, and their visitors, to think twice about what they are seeing. In all of the pieces I saw, the space was completely changed – urging spectators to not get too comfortable, and to constantly question what’s being represented. What’s real and what’s not? The other defining themes are how the past is affecting the present: from Roosevelt and Elvis affecting a lost young woman in South Dakota, to a Brazilian woman desperately trying to understand and stay connected to her heritage, there seemed to be a preoccupation with placement in the world, and how that affects us emotionally. As I head back to London I wonder how the next year will pan out: what will I learn from my past, and how will the grand political and pop cultural events of the weeks and months to come affect me and my circle of friends and family in the decades to come? One thing I do hope is to be able book a flight back to New York for next January’s festivals… what a theatrically nutritious, if chilly, start to the year.

New York Festivals attended by Terry O’Donovan in January 2015:

COIL Festival 2015, an annual performance festival in its 10th year, ran at PS122 throughout January.

Established 11 years ago, the 2015 edition of The Public Theater’s Under the Radar, a festival tracking new theatre from around the world, ran 7–18 January 2015.

The third edition of Prototype opera and music-theatre festival ran 7–18 January 2015.