One Step Before the Fall arrives at the London Mime Festival glittering with accolades from the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. It won the Herald Angel Award and was nominated for a Total Theatre Award for Physical/Visual Theatre. Inspired by Mohammad Ali’s battle with Parkinson’s the piece is a dense physical and musical exploration of the triumphs and loss that can result in such an extreme pursuit of pushing the body to its limits.

One Step Before the Fall arrives at the London Mime Festival glittering with accolades from the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. It won the Herald Angel Award and was nominated for a Total Theatre Award for Physical/Visual Theatre. Inspired by Mohammad Ali’s battle with Parkinson’s the piece is a dense physical and musical exploration of the triumphs and loss that can result in such an extreme pursuit of pushing the body to its limits.

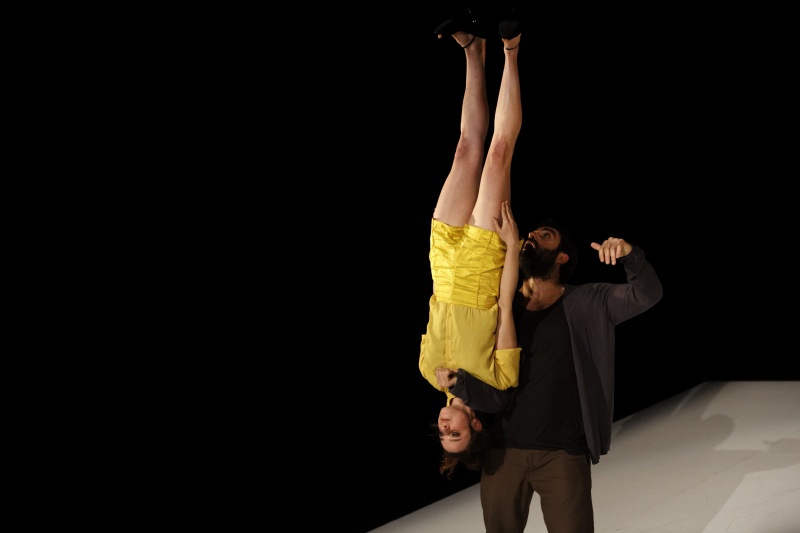

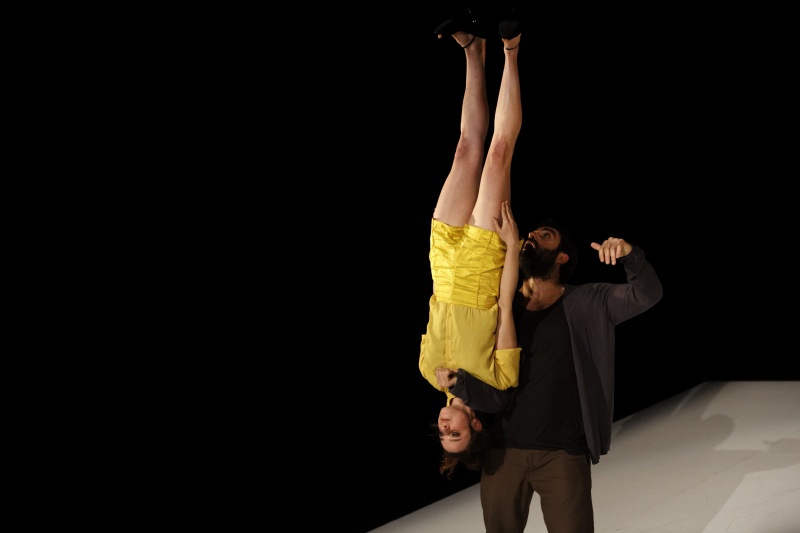

It’s not hard to see why the assessors handpicked it for the ‘physical’ award. Veronika Kotliková’s central performance is a grueling tour de force. Alone inside a boxing ring, her muscled body ripples as she flings herself across the stage in powerful thrusts and leaps. Most mesmerizing are the opening sequences in which she frantically shakes her limbs or head so fast that the image blurs in front of your eyes. As a symbol for a fraying mind, Kotliková’s frenzied movement achingly conveys the mind slowly breaking down, beautifully embodying a recording of Ali’s speaking which is almost completely incomprehensible.

Whilst it may appear to be a solo show, Once Before the Fall is in fact a duet. Kotliková is joined onstage by Czech Grammy winner Lenka Dusilová who creates a dizzying soundscape that propels, brutalizes and sometimes comforts. Standing behind a MacBook, guitar slung over her shoulder she is an unnerving figure, constantly fiddling with sound levels, fine tuning her vocal and musical loops. During one sequence her voice beautifully layers upon itself, hauntingly and gently growing in delicate sound. Reminiscent of French singer Camille, it’s a highlight of the piece, with both women beautifully but torturously in harmony with each other.

Elsewhere both sound and physicality became too repetitive and angry to clearly propel the action further, instead becoming so ear-splittingly loud it made me wince. Although I’m aware that that is more than likely the desired effect, these prolonged moments distilled the action, often being so intense that the piece became impenetrable.

An interesting addition to the Mime Festival, the performance is not an easy watch, but a powerful exploration of a fascinating and deeply upsetting condition.