Brendan Stapleton charts the influence of Commedia Dell’arte in live and onscreen performance over the past century, and praises a recent documentary about the legendary Joan and Barry Grantham

Commedia Dell’arte in its pure form began in Italy midway through the 16th century, and flourished for two hundred years. From there, it provided the impetus for the growth of many other forms and practices, including mime, pantomime, clown, slapstick, and physical comedy. We can see the influence of Commedia Dell’Arte in much of today’s live and onscreen performance. But let’s first go back to the roots.

The familiar figures of Pierrot, Harlequin and Columbine recall the burgeoning Commedia Dell’arte scene beginning in Italy midway through the 16th century. Growing up in the market place at the service of quack medicine men and such-like, it developed into a powerful entertainment for the common people – a culmination of various styles of performance skills, including acting, dance, mime and acrobatics. The indigenous culture that now existed in 16th century Italy was seen as a freeing of theatrical expression, returning to the use of characterisation that was far older, dating back to the obscure ancestry of Ancient Greece and Rome. Commedia, in its original form, flourished for two centuries before mutating and being absorbed into other forms such as mime and pantomime – although in its pure form, it has continued to exist right up to the present time (although sometimes undercover as we’ll see later).

Coming up to the beginning of the 20th century and the advent of film as an artform: Commedia was a clear influence on silent physical comedy. Laurel and Hardy were both Zannis, and Charlie Claplin was a classic Arlechino (all types of servant clowns). Later, Britain’s favourite of this genre was undoubtedly Norman Wisdom, whose slick and well-timed comic skills even conquered the United States where the ‘low birth’ loser was considered endearing.

We can see, therefore, that Commedia becomes integrated into each new artform or genre that evolves without necessarily being recognised for what it is.

The contemporary influence of Commedia Dell’arte can best be exemplified by none other than Cirque du Soleil. The French mime artist in their show Alegria is similar to the Marcel Marceau clown character Bip. In contemporary circus, theatre and Outdoor Arts festivals, we can see very many performances that owe a great deal to Commedia.

In recent theatre work, we can note the Richard Bean’s play One Man, Two Guvnors, an English adaptation of Servant of Two Masters (Il servitore di due padroni), a 1743 Commedia dell’arte style comedy play by the Italian playwright Carlo Goldoni. The play replaces the Italian period setting of the original with Brighton in 1963. The play, with Commedia inspired clown work directed by Cal McCrystal, opened at the National Theatre in 2011, then moved to the West End and Broadway and subsequently toured worldwide, bringing an awareness of Commedia to a wider audience (although Bean’s play was influenced by, rather than being a contemporary example of, true Commedia).

Yet often the provenance of such characters and performances isn’t acknowledged. When I choreographed Mike Bennett’s Glambusters, inspired by the early 1970s Glam Rock movement, I referenced many classic Commedia characters, but even the people who created the production would not have noticed or recognised these allusions.

We can also note that Commedia has also spawned many seemingly new performance practices that are in fact as old as the hills.

A good example of forgotten traditions was the emergence of the ‘living statue’ at street festivals worldwide in the 1990s – supposedly a new development. It had, in fact, been used by street theatre clowns and mimes for decades, and harped back to the travelling troubadours of days of yore, who excelled in portraying or parodying characters from their own cultures. In another personal example, I played a 1920s mannequin in the film Whoops Apocalypse, starring Rik Mayall, in 1985; and I subsequently performed as a dancer and footballer statue in a 1994 Opera North commission for the Munich Biennale in Germany, and the Manchester City 100th Anniversary Celebration.

In 2005, whilst working on a video-installation and performance with Greek visual artist Sophia Kosmaoglou, we sourced our human ‘still life’ image from the Victorian 19th century tableau vivant – the staging of scenes from popular paintings and sculpture where the participants hold postures and expressions for up to twenty minutes. This form can even be traced back to Goethe’s 1809 novel Elective Affinities in which he describes such a performance as ‘this living reproduction [that] far exceeded the original, sending the audience into raptures’.

So there are just a few examples of Commedia breaking into the world of contemporary performance. Let’s now look to our TV screens.

A good example from TV is the BBC’s television sitcom Faulty Towers where we see the master-servant relationship explored, and encounter various eccentric characters that reference the stock characters and archetypes of Commedia. John Cleese is El Capitano/The Captain and the Spanish waiter Manuel The Servant – his depiction of social ineptitude is physical comedy par excellence. The Major is a Captain Doddery; the character Polly (played by John Clesse’s wife, Connie Booth, who was co-writer of the sitcom) a mischievous Columbine.

We can also note the influence of Commedia in 1970s sitcom Are you being Served? The character John Inman portrayed, with his ‘I’m free’ catchphrase, portrays a good example of the physical comedy set-pieces taken from Commedia that we call lazzi, with comedy footwork customising his character. Also in the 1970s, Bruce Forsyth had a specific foot sequence in his introduction and in the Kenny Everett Video Show proved he was the king of the unpredictable lazzo.

Traditional Commedia with its masks and costumes might exist in a cultural backwater, but many of the stock characters of the form are constants in the cultural landscape, despite changing tastes in comedy and family entertainment: film, dance and physical theatre shows feature Pierrot characters that can be any gender; and the brilliant comedy of Pantomime dames, which were undoubtedly ahead of their time when they emerged centuries back, owe much to Commedia.

Commedia is still seen as a ‘minority art’ for contemporary ‘eccentric practitioners’ who exist as an subcultural underground movement. Yet occasionally a name surfaces from that underground…

Barry Grantham, described by British Commedia Dell’arte, expert Richard Handley as ‘a national treasure’, has a lifetime’s experience in Commedia D’ell’arte, Vaudeville and Eccentric Dance that took him and musician wife Joan from their early days treading the boards in ballet and musical shows, through years working the British Variety circuit, on to many decades of teaching, directing, researching and developing both Commedia and Eccentric Dance.

A recently released film entitled Barry and Joan, directed by performer and filmmaker Audrey Rumsby, who has trained with the Granthams, gives due credit to both halves of this creative partnership. Born into a theatrical family, Barry was imbibed with the traditions of Commedia Dell’arte, developing his work with traditional acting, mask, ballet and physical comedy; performing from an early age and teaching at the family’s dance school. He met his multi-talented wife, Joan whilst they were working together on a West End show. As the publicity for the film says:

‘He was an incurable performer who loved to cross-dress. She was a dancing piano genius. She spotted his legs when they met in a musical. Seventy-five years later, they are still married, performing, and teaching.’

The film is demonstrative of this wonderful work-life partnership and highlights the couple’s contribution to Commedia, Eccentric Dance and British Music Hall.

Barry Grantham has concurrently made a name for himself as a writer and teacher with an advanced understanding of Commedia Dell’arte. Barry notes that the Clown or Fool is the natural and historical bridge between all the singing dance-mime and circus visual gags and associated imagery on the stage, television and film. Barry Grantham has been studying the revival, re-creation and development of Commedia, and moving the knowledge of the form forward with his research, teaching, performing and lecturing. With an awareness of how the form has fallen out of fashion in contemporary performance circles, Barry says that one can choreograph Commedia Dell’arte but it is not wise to refer to it as such because in the modern context it is so often misunderstood.

Let’s hope that Audrey Rumsby’s film goes some way to redress this, bringing awareness of the value and power of the true Commedia dell’arte style. It is refreshing to see in the film how many young drama students are bowled over by Barry and Joan’s work, pledging themselves to pursuing the work in their future theatre practice.

Perhaps a minority artform, and often misunderstood, Commedia Dell’arte is nevertheless alive and kicking – its influence apparent everywhere in contemporary live and onscreen performance.

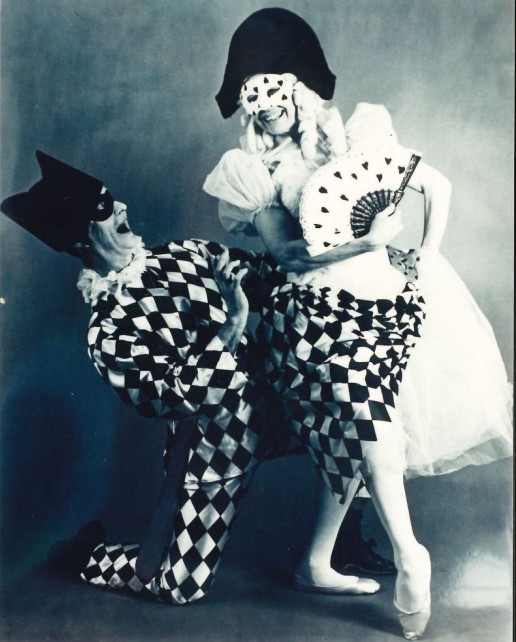

Featured image (top): Still from the film Barry and Joan, featuring director Audrey Rumsby as Pierrot with Barry Grantham.

For more about Audrey Rumsby’s film Barry and Joan, see https://barryandjoan.com/

The film is released on DVD in November 2022, and can be ordered here.

Barry Grantham’s two volumes on Commedia Dell’arte, Playing Commedia and Commedia Plays are available from Nick Hern Books: https://www.nickhernbooks.co.uk/barry-grantham Barry Grantham (with Bill Tuck) is now running the Zannizine – an online magazine devoted to Commedia, and his novel of the 17th century Commedia player Mezzetino is almost ready for publication. Joan is working on Joanie’s Song Book.

For more about Brendan Stapleton’s work see

www.brendanstapleton.com