The Iranian director Nassim Soleimanpour first came to prominence in the UK in 2012 when his play White Rabbit, Red Rabbit was first staged. This was a play with no rehearsals, no director, and a script that the solitary actor only saw the moment play began. At the time, White Rabbit, Red Rabbit was interpreted as an exploration of Soleimanpour’s own status in Iran: a conscientious objector and therefore banned from travelling. Soleimanpour himself, though, declared that he was more interested in the social phenomenon – that of obedience. In either case, the conceit of leaving the embodiment of the playwright’s script up to the actor and the audience in the moment of performance served as a fertile metaphor.

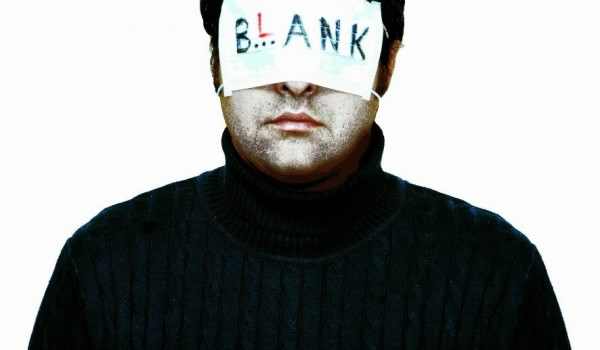

Soleimanpour’s latest play Blank uses the same device. Each night a different performer finds themselves in front of an audience, with only some blank A4 paper, a marker pen, and some tape. The stage manager produces the play from an innocuous brown envelope, and the play begins. There is some preamble, an explanation of the text’s ‘blank’ spaces in each sentence – spaces which the performer, and later on members of the audience, are to fill in.

Tonight’s performer is Franco-British comedian (or ‘professional idiot’ in his words) Eric Lampaert: 6’4”, whip-thin and (according to him) fresh from a wedding. Lampaert is a genial ‘host’, with an easy manner, and a good line in shifting between self-deprecation and gently scathing observation. In this context he deftly manages the negotiation of the empty spaces in Soleimanpour’s sentences, and ensures that Soleimanpour’s somewhat philosophical text, which imagines first the past and then the future, avoids becoming too solipsistic. Soleimanpour’s structure demands a certain collective endeavour on the part of the audience, though this is quite tightly guided – the audience only shaping the specifics of the story rather than the structure of the piece, so the actual task often feels more of a party game than an actual collective authorship. лицензия казино онлайн

Although this collective authorship serves as the basis for Soleimanpour’s reflections, the shift in Soleimanpour’s writing from the ‘narrative’ of the tale to the ‘reflective commentary’ is a little heavy-handed and in some ways the reflective paragraphs lay out too clearly what Soleimanpour wants us to understand about the nature of writing. In this way, the play becomes a little too didactic, and whilst an entertaining and at times moving experience, everything is on the surface a little too much.

Blank is presented at the Edinburgh Fringe by Aurora Nova