Protein Dance’s director Luca Silvestrini collaborates with musical director and performer Orlando Gough in a piece that seamlessly layers speech, movement, and a cappella singing into an all-encompassing spiritual experience. The all-singing, dancing, talking, and waiting ensemble of eight dash about our tables to serve the audience in a constantly churning kaleidoscope of floor patterns. Somewhat akin to the shapes plotted in Renaissance court dances, which sought to mirror the cosmos and find perfect harmony, the performers undulate and circle around side aisles of dining tables framing a central performance space. The studio is transformed into a dining room and then into a cathedral dedicated to the worship of food. Framed by a raised microwave at the altar and the kitchen clock at the opposite end, the acoustics tie this ethereal world together, bathing audiences in harmonies that make for tingling spines and dropped jaws.

Protein Dance’s director Luca Silvestrini collaborates with musical director and performer Orlando Gough in a piece that seamlessly layers speech, movement, and a cappella singing into an all-encompassing spiritual experience. The all-singing, dancing, talking, and waiting ensemble of eight dash about our tables to serve the audience in a constantly churning kaleidoscope of floor patterns. Somewhat akin to the shapes plotted in Renaissance court dances, which sought to mirror the cosmos and find perfect harmony, the performers undulate and circle around side aisles of dining tables framing a central performance space. The studio is transformed into a dining room and then into a cathedral dedicated to the worship of food. Framed by a raised microwave at the altar and the kitchen clock at the opposite end, the acoustics tie this ethereal world together, bathing audiences in harmonies that make for tingling spines and dropped jaws.

The subject matter starts in the everyday: the routine and the habit of eating. It quickly descends into the depths of the social and emotional conditions that are so tightly interlaced around the act of eating. Sometimes dark and referencing horror, often sensually infused with tantalising text and innuendo, and consistently silly, each scene is abundant with content. The Meat Song sees performer Donna Lennard leaving a smear of blood along the shiny, white tiled wall as she sings with the purest of voices. Full of quips and quibbles from juices to pomegranates to marinating loins, the songs cover a myriad of topics. The lyrics highlight the muddle of mixed messages surrounding food, from health facts to cooking instructions and forbidden items to the notion of choice, demonstrating the contradicting information that influences our relationship with food today. Little ditties such as Don’t Eat That, Eat This, feeding like birds to feeding a child, all form content for speech, movement vocabulary, and narrative. The dance of the slaughter house begins with two female performers’ heads on plates. It becomes macabre with a clumsy, ungainly weighted plod carefully intertwined with a sense of noisy chaos, a subtle tension between compliance and panic, voice and movement.

As a miniature course is served up to each table of viewers, we are invited to enjoy a sensory experience by our waiters. Rolling a cherry tomato down your face before you pop it reveals flirtatious, sensual, and silly responses as audience members join their fellow diners in a joint eating exercise following simple instructions. Each micro-meal, revealed under a bright white spotlight as if beamed down from a deity, provokes taste, textures, and social metaphor. Unwitting diners close their eyes, count down their chews, and are given permission to swallow or feed their neighbours in a cacophony of innuendo and metaphor.

The scene where performers Martin George and Louise Sofield sit across from each other on a table for two exemplifies the form of the piece as a whole both in structure and beauty. The two central diners are encircled by a chorus of breaths, notes, and words. Their conversations, thoughts, and reactions both spoken and unspoken are sung or danced in stark juxtaposition with the couple’s static posture and stilted silences. The meal frames larger issues as tempo and text increase and repeat, erupting in climatic tableaus and one-liners. After sudden silence and stillness, the scene transforms to that of an elderly man being spoon-fed. Now caring and the end of life is the focus with guttural noises, hiccups, and a poignant kiss giving this simple moment both beauty and gravitas. This sort of detailed build and seamless transformation is what the piece does well and often.

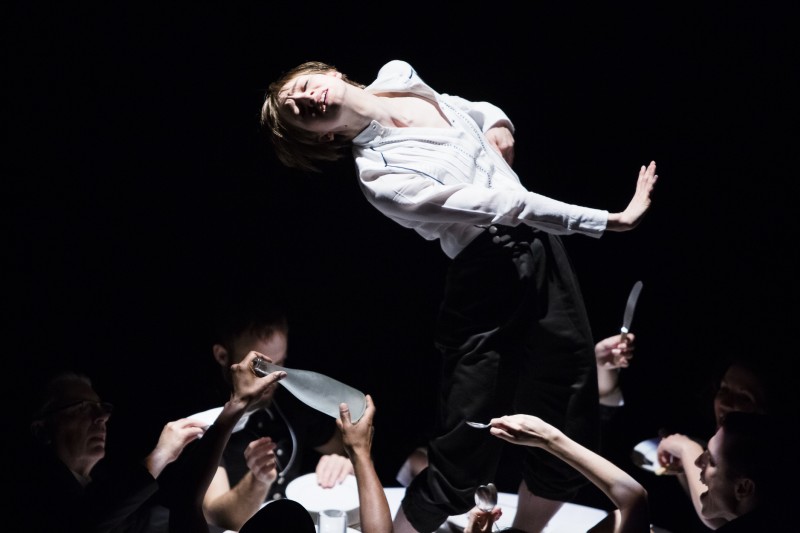

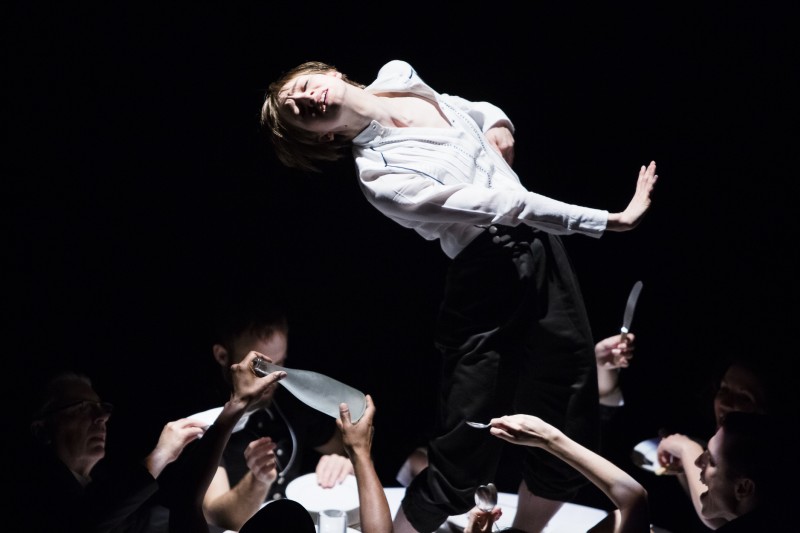

A series of rituals highlight personal stories where food is consumed under emotive circumstances, taking the audience through compelling highs and lows. The constantly revolving content feels like an indulgence in sensory experiences and the pleasure and sparkle in the performers’ eyes as they busy themselves around their diners make performer-audience relationship feel powerfully intimate. Often sexual or sensual, the scene climaxes bring to mind the sense of ecstasy that Baroque artists strived to capture, such as Bernini’s Ecstasy of St Teresa. This is reiterated by the spiritual references that are played upon throughout.

After the microwave dings and dessert is served, the piece ends with a prayer-like narration of a list of ingredients that it contains, deconstructing what has just occurred and clearing the plates ready for the next service. Senses heightened and appetites aroused for more, May Contain Food with its rich, fast moving text could easily be seen again. The acapella soundscape mastered by the ensemble is in constant transition meaning that voices move in and out of audience space and this ethereal surround-sound ties the work together. It may contain food but the product is far more than the sum of its parts.