No Future? Edward Taylor celebrates 40 years of the Whalley Range All Stars, street theatre makers and animators extraordinaire, whose co-founders are now coming full circle back to their roots

We’re 40 years old this year (2022), but let’s face it, we’re a street theatre company – we’ve made the faintest of marks (if any) on the face of culture. I’m not comfortable blowing my own trumpet but when you’ve managed to reach the age of 40 someone has to do it.

The Whalley Range All Stars are Sue Auty and me (Edward Taylor). We met in 1981 at Leicester Marina where Horse + Bamboo were creating a site-specific show. Sue had also been working with Dogtroep from Amsterdam who (on the basis of some photographs of a show ) invited me over to work on a huge show at the Melkweg. This was followed by a summer tour of France, Belgium and Holland in 1982.

When our participation in that tour ended we were at a loose end, with a few ideas of shows we could do. We put together a sandwich-board show where a variety of paintings on hardboard animated a story involving a flat-fish that could talk. We performed it at Yerbury Park off Holloway Rd. in London. It got a nice reception from a small audience. One person asked who we were – at the time, Sue was living in Whalley Range and we’d had to compete with a band on a stage called Holloway All Stars so she quickly said ‘We’re the Whalley Range All Stars’. That name proved impossible to shake off.

I moved up to Manchester and we started to make shows where and when we could – 80% of the time we didn’t get paid so were lucky that signing on wasn’t as onerous as it is now and the cost of living wasn’t nearly as expensive. Otherwise…

The nearby Chorlton Tennis Pavilion, run by Victor Hyman, hosted a lot of our early shows including Halloween and Xmas specials. CP Lee (of Alberto Y Los Trios Paranoias fame) set up a venue for lunchtime theatre at the Britons Protection pub. Jeremy Shine was promoting alternative theatre all over Manchester. He gave us our first ever paid gig. He took over Manchester Festival, created the Castlefields Carnival and worked with Stella Hall to get the Green Room theatre and arts centre off the ground. Socialist councils put money into entertainment and art that existed outside of built venues, so there was a national circuit of gigs. There were a lot of opportunities and we were able to get paid for many of them. Both Stella and Jeremy have continued to support our work over the years.

Embarrassed by the levels of unemployment, Margaret Thatcher’s government set up the Enterprise Allowance scheme in the early 1980s. You set yourself up as a company and were given a year’s wages (£40 per week, as I remember) to establish yourself. We bought a transit van and rented a workshop which wouldn’t have looked out of place in a Tarkovsky film.

God forbid that I should ever mention Michael Heseltine, but his Garden Festival scheme provided welcome blocks of work for companies such as ours. Nobody working at those festivals seemed remotely interested in what they were booking so it was possible to experiment wildly with the plentiful audiences without any consequences. A far cry from the Millennium Dome in 2000 where our Headless People animation was sent off-site by the organisers in case we bumped into the government minister who was visiting that day and caused an unwelcome photo opportunity for the press.

Our early shows involved a lot of talking and my role became that of a stand-up comedian. We felt that the visual aspects of our work were being over-shadowed by the non-stop patter, so looked at ways we could avoid that.

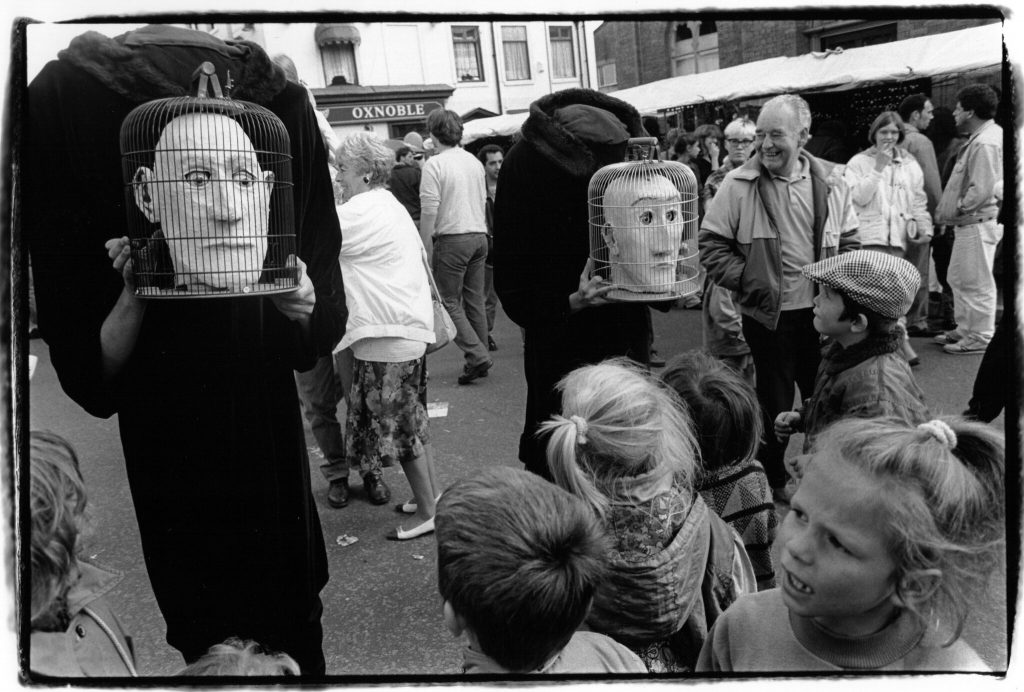

The aforementioned Headless People (made in 1992) was the first one we created where there were no words: two headless figures carrying their heads in birdcages. Greville White (RIP) created the ingenious mechanisms that caused the eyes to move and blink. It was revelatory to see and hear what the audience made of it when we didn’t nudge them in a particular direction by talking to them and thus giving them ideas. It was even more revelatory to take that show to Arkhangelsk in Russia and experience how the image provoked a very different and powerful effect on an audience not (yet) over-saturated with entertainment.

If the 80s were about creating 30-minute long narrative shows the 90s were all about experimentation.

We created a big clock on a freight box where we (me, Sue and Laurence Lane) were the automata performing on the hour. We put together a band of Ear Drummers playing improvised and rehearsed percussion pieces. We put our disembodied heads in glass cases in Manchester Museum’s vivarium, where our minimal movements complemented the frogs, toads and lizards who were full-time residents. We revealed the secret life of mannequins in shop windows. We made a musical box featuring a ballerina with a dancing face…

The Parade of the Senses in Manchester city centre converted each sense into carnival form; our Arctic explorers featured puppet husky-driven luggage; and Salford Art Gallery commissioned us to create an exhibition called These Foolish Things, based on cabinets of curiosity. That exhibition made with Steve Gumbley (a founder member of IOU and Welfare State) was a blueprint for many of the ideas we explored in the 2000s as well as a development of a street theatre show, The Cabinet of Unearthly Delights, which we made in 1987; and an exhibition, Curiouser & Curiouser, that we made for Oldham Art Galley in 1991.

We met Bill Gee (then promoting events at Canary Wharf) in 1998 at French street theatre festival Chalon dans la Rue. Over lunch he asked us what plans we had for the future. We mentioned a couple of ideas with no thought that we were pitching for a gig. Later that year he phoned us wanting to commission one of the ideas called Headcases. This was a series of big rectangular boxes on stilts with holes on the underside. You crouched underneath and put your head in one of the holes. Inside the box you’d see your head as part of a tableau reflected in a large mirror.

There were thirteen of these in total and we played around with what your head was doing as part of the image. One tableau involved finding yourself on a railway track which stretched into a dark tunnel behind your head. When we first presented it in Canary Wharf a particularly confident stage designer told me how we should have done it using sound and the latest film technology. I felt that by restricting the use of technology, we allowed our audience to come to their own conclusions. The final Headcase featured a live performer seen through a bead curtain. Several people thought it was a hologram rather than the ingenious use of the most basic materials possible.

This idea developed into Head Quarters – a sideshow where the audience sat in a strange booth, five people opposite five more people. A suspended box above them with holes on the underside was lowered onto their heads. Inside the box they found their heads in tiny beds in a weird dormitory. There was one performer behind each row of five who emphasised the night-time atmosphere with plumped-up pillows and bed-time toys. Pat Selden was the third performer, and Andy Plant made the booth.

This developed into Bedcases where five people were put into a large four-poster bed and wheeled into a tent. They found themselves in a slightly cramped bedroom. Five performers animated this space using a bookshelf with a life of its own, an oversized picture book, the sight of a flock of geese flying overhead and a lullaby. We commissioned Clive Bell to compose the soundtrack. Andy Plant designed and made the booth.

These two shows were vivid theatrical experiences for the participants but there’s only so many ten-minute-long shows for small amounts of people you can do per day. A lot more people saw the outside of these shows (which were intriguing rather than visually striking) than experienced what was going on inside. The next show solved the problem of balancing the outside and the inside…

PIG featured a 30-foot-long inflatable sow asleep on her side. You could hear her snoring and her nose twitched from time to time. A farmer invited ten people into the pen. They were given curly pigs’ tails to put on and directed towards the nipples. The nipples were removed and they put their heads into the holes. They watched a ten-minute-long show featuring two farmers and their daily routine, inside the pig’s belly, whilst anyone walking past saw ten piglets suckling at their giant mother. Penny Saunders of Forkbeard Fantasy designed the inflatable body; Andy Plant created the pig’s animated head which was made with the participation of Max Orton (RIP) and Ali Wood. Steve Gumbley was the extra performer and helped create the show.

This was an incredibly successful show and toured throughout the world.

If I may be so bold, one piece of advice we’d give to any emerging artists is to never sit on your laurels. Use the opportunity that a successful piece of work gives you and carry on making new shows to offer the promoters. The longer you put off making new work the more difficult and pressurised it becomes.

After a few years we handed touring duties of PIG over to a separate team so we could concentrate on making new work. Among this team were Jack Lockhart, Scott Tomlinson, Tom Hogan, Katy-Anne Bellis, and Chris Davies – all of whom worked with us on other shows.

Whilst PIG was still touring we went back to creating longer narrative-based shows. Compost Mentis was designed as a mess-making reaction to those short shows where everything needed to be re-set quickly. We worked with composer/sound artist Matt Wand who decomposed Clive Bell’s soundtrack, which featured Harry Beckett (RIP) on trumpet. (Harry was Charlie Mingus’ go-to trumpeter when he toured in Europe and is our only link to anything that’s cool.)

Brain Wave featured a large head in a garden shed, Ye Gods featured a model town with three fallible gods towering over it. These three shows were made with sculptor Bryan Tweddle and performer Peter Finegan. Their contributions have been invaluable in the development of our (errrm) mature phase!

I could go on, so I will.

We made Future – a three-day installation in a disused shop. A giant plant had burst through the first-floor window and you could see the roots through the ground floor window. From time to time the plant burst into flower. A team of five miners entered the shop and foraged for food. You could see the food they found being processed and packaged. The packaged food was then taken outside and raffled off to the audience. A vision of a future where nature has taken over the declining high street and we eat what we can find.

We made Imaginary Friends – ten performers and ten life-sized doppelgänger puppets playing in and with the streets. It was part improvised choreography and part a series of set pieces. Chris Davies composed the songs we sang. We worked with Babok, an Amsterdam-based performance company who share our adventurous approach and who have the same theatrical roots (Netherlands company Dogtroep).

We made Cake, an indoor table-top object theatre show for children, with Beka Haigh. We made The Best of All Possible Worlds, a very loose adaptation of Voltaire’s Candide which featured two Deaf performers. The decision to work with Deaf performers was a leap into the unknown but we make primarily visual work so there was no reason why we shouldn’t. Our decision was vindicated by the participation of Adam Bassett, Nat Mason and (in the second year of touring) Rebecca Dixon who all brought a completely new level of performing to our work.

We even got someone full-time in the office: Jez Arrow, who took care of finances and marketing.

There’s more – an afternoon of extreme pedantry revealed that we have created precisely 100 shows/installations and events. We toured to 25 countries over 5 continents.

(Why so pedantic? When we first started Warner Van Wely of Dogtroep advised us to tell people what we were doing otherwise no-one would ever know. So I wrote down every gig we did and at the end of every year I sent a report of our activity to North West Arts Board, back in the days when there were regional as well as a national branch of the Arts Council, who often as not hadn’t even funded us. Old habits die hard I guess.)

However this summer (2022) will be our last. A combination of Covid, Brexit and being an over-familiar 40-year-old has done for us. When we got Arts Council England (ACE) regular funding in 2003 after 20 years of scraps off the funding table they said to us: ‘How can we help you make your best work?’ When we re-applied in 2011 they said to us ‘How can you help us reach our aims?’ Ultimately we couldn’t help them and so were dropped from regular funding in 2015. In fairness ACE has kept on funding our projects, but the street theatre circuit is changing, the funding forms are asking too much of us – and we’ve also decided to look at other avenues for creating work rather than watch our tours get smaller and smaller.

So, on to new ventures:

Sue has just created Floooooooot – an indoor show for babies, working with classical flautist Kathryn Williams. I’ve drawn two comic-strip books about Godzilla which were published by the Lakes International Comic Arts Festival in Cumbria (copies are still available!).

We’ve also created two kamishibai shows – a Japanese form of story-telling using A3 sized colour drawings and narration. Sound familiar? Think of that sandwich-board show in Yerbury Park 40 years ago. Only these kamishibai shows reveal the experience we have gained from the following 40 years of work. Screen Argyll (run by Jen Skinner and Jack Lockhart) filmed one of the stories, Godzilla v. the Fatberg, and toured it around the Western Isles with the original 1954 Godzilla film. The audience were given masks from our Godzillatown installation to wear.

Sue and I came up with the ideas, kept the show on the road, and made large parts of each creation. But we are enormously in debt to all the performers, makers and musicians who helped make those ideas even better and richer. Our first extra performer was Terry Naylor back in 1983 and the team for Godzillatown (2021) are Pete Finegan, Katy-Anne Bellis, Tony Cairns and Chris Squire. There are too many people to mention here, but we thank them all.

It’s all very well making shows, but you need opportunities to show what you’ve made. We are forever grateful to the network of promoters and festivals, both in the UK and throughout the world, who nurtured us and booked us time and time again.

Conversations with other companies gave us tips on how to keep going. Andy Coombes of Bob + Bob Jobbins, Tim and Chris Britton of Forkbeard Fantasy, and Mary Turner (RIP) of Action Space Mobile were especially generous in that respect.

But the work? Well, someone had to do it.

Featured image (top): Whalley Range All Stars: Future (at SIRF 2014). Photo: Jez Arrow

For more about Whalley Range All Stars and the latest projects from Edward Taylor and Sue Auty, See https://www.wras.org.uk/

For future non-WRAS work please check the Facebook pages of Sue Auty and Edward Taylor Pictures.

To buy Edward’s comic books go to www.edwardtaylor.pictures