The set design of Told by an Idiot’s My Perfect Mind looked clinical and was full of disparate objects: screens, a wind machine, table and chairs, and a thundersheet from which a ramp sloped downwards at an awkward gradient. I immediately drew a blank: how would these things come together coherently? The smooth hessian or stark white of the objects’ neutral colouring suggested negation, a purposeful reticence of design anticipating noise and vividness. A doctor with a dodgy German accent (Paul Hunter) opened the performance with a lecture on the scientific workings of the brain. But this doctor was fascinated more by when the brain goes wrong than when it ticked over undisturbed, demonstrating the former by rolling a ball down the slope into a tray of crockery. The sound of smashing did everything to alert the audience to the split-second violence of medical malfunctioning. How rapid, we were led to think, comes the disaster.

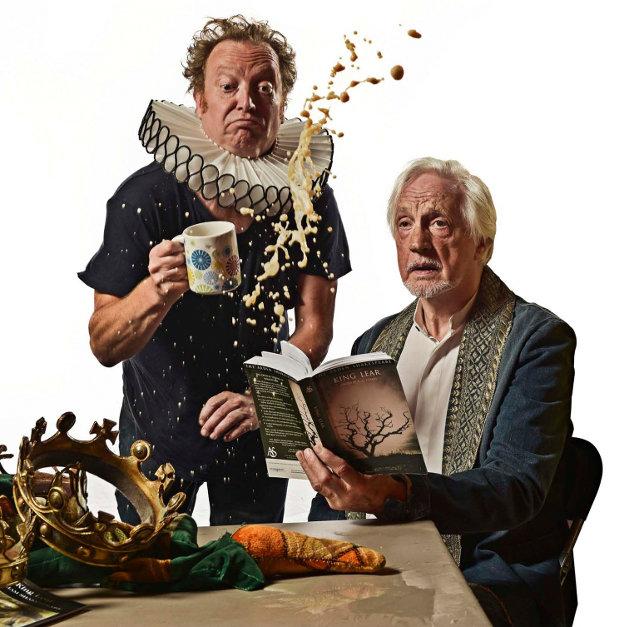

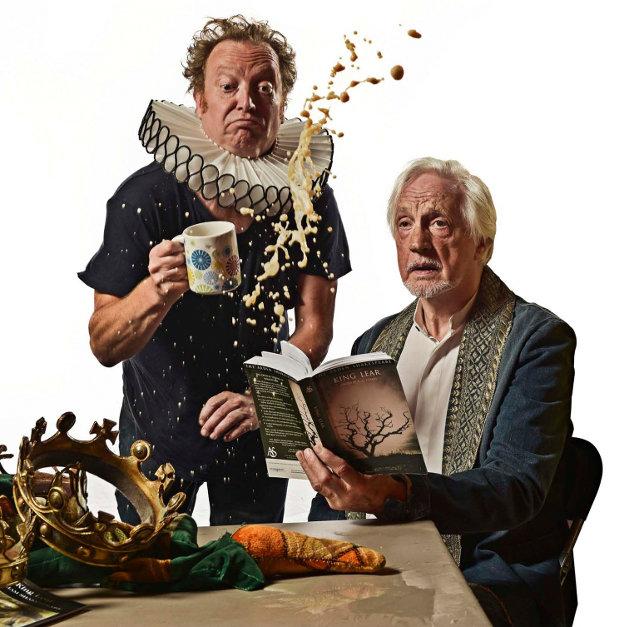

For Edward Petherbridge, the disaster arrived at the worst time (although there is never a right time). The cruel irony for this classical actor was being violently struck down by a stroke while rehearsing for King Lear in New Zealand. The irony was not only cruel but double, the production being the first occasion on which Petherbridge would have acted in the coveted title role. Despite the physical impossibility of fulfilling the demands of the performance, strangely, perhaps even miraculously, Petherbridge remembered all of Lear’s words. But though language was willing, the body was not. And while Lear inhabited his body, memory of the actor’s own life was cut loose from its moorings.

The life of the stroke victim is a broken narrative whose fragments are constantly wrenched free from oblivion. My Perfect Mind explored this scenario with gentle wit and pathos – and at times a little nervously too. Petherbridge was a stylistically astute if inevitably flawed interlocutor for the shape-shifting Hunter, who stepped in and out of character in comic attempts to bring the actor’s family and professional comrades back from the brink. As is to be expected from Told by an Idiot, Hunter’s clowning had an acute focus, which is just the kind of attention required of one goading the amnesiac back into the full bloom of memory. Such was the reliability of his prompting, the wide-eyed manner with which he hung on to Petherbridge’s every word and physical gesture, it was tempting to view Hunter as the kind of fool from whom Lear himself might have benefited. By contrast with Shakespeare’s mad king, though, this was a relationship in which listening was reciprocal. At times Petherbridge acted the fool himself, if only to prove to his companion that he can serve irony too, and that memory and logic were on the mend. Yet the improvisational air of some moments, in which a nervous pause interrupted the flow or a fact stuttered into existence, opened up the sense of a halting articulation fought at great emotional cost.

Although both actors hail from contrasting theatrical traditions and generations, their quirky coupling made total sense. There were touching echoes of Morecambe and Wise: their scrambling for props, their deft navigation of a set replete with physical obstacles, the frequent misfiring and recovery of lines, the puns and wink-winks. Given his stature as a classical actor, not to mention his acquaintance with some of the greatest performers of the twentieth-century (the audience was treated to some revealing anecdotes in relation to such figures), Petherbridge could almost be the lost guest of a Morecambe and Wise Christmas Special.

My Perfect Mind was eminently entertaining but the performance was no mere entertainment. One favourite detail for me amongst many was the tendency for a chair to slide a few feet down the slope no sooner had Hunter sat on it. Catching himself in time by grabbing the table’s edge, this moment of classic physical comedy made me laugh while reminding me that nothing was ever as stable as I might like to think. If I wasn’t quite on the edge of my seat, perhaps I should have been. And to be sure I was mesmerised by the hugely comic but peculiarly gripping rendition of Shakespeare’s storm scene (Morecambe and Wise again). It is testament to Told by an Idiot’s idea of putting on a show about not playing King Lear that I walked away from the theatre glowing but also with the melancholy thought of having made contact with a lost moment of glory.