Talking with John Wright can be a little daunting at times. He is affable and approachable, but at the same time he always seems to have something on his mind. It is only when you start talking about theatre, that you realise it is probably this subject that has been distracting him. As soon as the topic is broached, his eyes seem to light up and he speaks with excitement, determination and passion on his own views of the theatre world.

John Wright has been teaching and directing for over twenty years. He was a co-founder of Trestle Theatre Company and continues to work with Told by an Idiot. He conducts workshops all over the world, travelling as far as Hong Kong and Singapore to direct for international companies. He's currently writing a book about his approach to theatre, and has recently returned from Edinburgh after directing the new company, The Way We Are Over Here, in The Lion, The Witch and a Bag of Chips at the Fringe Festival. Fortunately, I managed to catch him on one of his quiet days at home in North London. I wanted to ask him about his approach to theatre.

There are four main influences that John Wright holds dear. The first is Lecoq and his concept of ‘Toute Bouge' (that everything has a movement quality) and ‘Mime du Fond’ (the fundamentals of movement). The second is Monika Pagneux, who taught him the concept of 'complicite'. The third is Philippe Gaulier, who taught him how to play. And finally, there are the teachings of Moshe Feldenkrais; Wright spent four or five years working with Christopher Connelly, who set up the Feldenkrais School in Britain, exploring the idea of awareness through movement. When taking part in a John Wright workshop, one can usually expect some sort of floor-work derived from the Feldenkrais Technique. 'I nearly always start with some sort of physical softening for the actors,' he tells me. 'I have about fifty or sixty Feldenkrais lessons that I draw on and I've kind of made my own movement approach. I use it to find “complicite” – with yourself, with others, and with objects and space.'

Wright talks about 'complicite' as sharing the vision, being in the same game as everyone else. He uses the French word because it sounds a lot more like an adjective than a verb. Feldenkrais taught that you shouldn't look at the end, but only at the bits you create as you go along. He also encouraged his students not to criticise and believed that less is better than more. All of these principles appear in Wright's work, as he explains: 'The idea of subtlety, the power of passive as opposed to aggressive movement, the way in which the body learns to retain things – these ideas are fully embedded in my approach to acting. From here I progress to using impulses – the idea of “complicite” gives me an open canvas on which to exploit an impulse.’

When working with Wright, an impulse can come from anything you choose – a mask, a hat, a pair of shoes, from the breath, or from some sort of physical energy. In other words, anything that the actor might choose to bring into the rehearsal room, as he explains: 'My preoccupation as a teacher and as a director is with the performance text. The performance text is the invention, the physicality, the individual skill and quite unique personal qualities that actors bring into the room. My work starts from there. If you put the emphasis on the performance text then everything changes, because you bring the play into the group of actors, you don't bring the group of actors to the play.' The emphasis is on an attitude of openness and playfulness, so that investigation and experimentation can be brought into the rehearsal room. Wright's actors are given an opportunity to find things for themselves, as he says, The stress is always on discovery – that's the real tenet of my work.'

When talking about his approach to theatre, Wright often uses the words 'pleasure' and 'play', and he is adamant about their importance: 'If you start using words like these, immediately people think you're somehow devaluing things, that you are somehow trivialising things and turning the profound into the vacuous. But it doesn't happen that way. If an actor on stage is having a really wonderful time, that pleasure is infectious – it communicates with the audience, allowing him or her to go further, to take more risks.’

John Wright's work relies on the idea of fun. Performers who work with him should enjoy what they're doing and through this sense of 'play' find ways to free themselves and discover new ways of telling stories

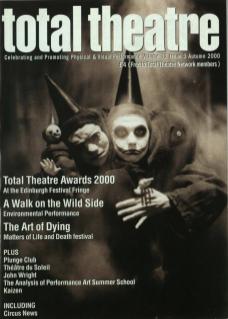

One of the primary methods of discovery in Wright's approach came to him almost thirty years ago, after studying different writings on Jacques Copeau. Copeau's method involved putting a handkerchief around the performer's face to make them feel less self-conscious. 'When I tried Copeau's method with a handkerchief, it was a disaster,’ Wright tells me. However, he took the idea a stage further and managed to persuade a technician he knew to make him a set of masks, which then became the foundation of a great deal of his early work, particularly with Trestle. ‘Being transformed by a mask took the ego out of everything we did,’ Wright explains. ‘We were then in a position of being able to make the masks, audition the masks, and make the set before we'd written the play.’

The idea of transformation comes up frequently as he talks about his mask work, the way that you can change species or sex, to appear more beautiful or more ugly than you actually are. Masks also give you the feeling of distance and of being hidden, which can be liberating. The mask is another tool Wright uses to find the impulses that he wants to exploit. He talks about using these impulses to constantly work beyond the self, to achieve a level of inspiration which takes you beyond what you think you can do (what the Balinese refer to as ‘taxu'). His latest ideas incorporate many of the discoveries he has made over the years.

‘The more I work with masks the more I'm going away from that. I'm using these elements, but I'm trying to take them out of the genre debate. Once you start using words like melodrama or tragedy, the resonance that comes with them tends to get in the way. So I'm looking at different ways of being on stage. I talk now about being better than you are, playing worse than you are, playing the way you are, and playing in a manner that is nothing like the way you are.’

‘Playing better' means playing the ideal – looking at the hero, the mother or the huntress – while ‘playing worse' explores the grotesque, being more stupid, more ugly, distorted from the way you are. ‘Being yourself’ is, as Wright says, just the idea of letting the text speak for itself, cutting away all the clichés, while ‘playing nothing like yourself’ envelops you in a cartoon-world, a world of fantasy, of shape and three-dimensional form.

For Wright these are new explorations, culled from old ideas and games, and reformed into a new discovery. As for teaching, he has decided to break free from the institute: 'I am basing my teaching in an entirely independent way. My main teaching is now entirely in my workshops, it's not connected to any institution. I still have a connection with Middlesex University, but Middlesex is now not a culture that has enough space to accommodate the detailed work on acting and performers that I teach. My work is now found in short intensive courses that I do all over the world, it's now found in my practice with my company and with other companies, so there's a constant cross-fertilisation between my teaching and my theatre practice.'

John Wright is currently setting up a ‘virtual school’ on the Internet, a means of networking the different workshops and production initiatives he takes part in all over the world.