‘It is necessary to look at how beings and things move, and how they are reflected in us.’ – Jacques Lecoq

In La Grande Salle,

where once sweating men came fist to boxing fist,

I am flat-out

flopped over a tall stool,

arms and legs flying in space.

Beneath me the warm boards spread out

like a beach beneath bare feet.

I'm on my stool, my bottom presented

to milling passers-by.

Someone takes the offer

and starts a naughty tap-tapping.

‘Who is it?’ I cry gleefully. ‘Who is it?’

Tap-tap... it raps out a rhythm... tap-tap-tap.

Then it walks away and

I turn upside-down to right side up.

‘Who was it?’

I see the back of Monsieur Jacques Lecoq

as he leaves the Big Room

with his envoy of third years in tow.

Brawny and proud as a boxer walking from a winning ring.

He turns, and through creased eyes says

‘It was me.’

– Kristin Fredricksson

Steven Berkoff writes: Jacques Lecoq dignified the world of mime theatre with his method of teaching, which explored our universe via the body and the mind. He taught us respect and awe for the potential of the actor. Through his techniques he introduced to us the possibility of magic on the stage and his training and wisdom became the backbone of my own work.

He taught us to cohere the elements. To release the imagination. He also taught us humanity. He was the antithesis of what is mundane, straight and careerist theatre. He taught us to be artists.

Andrew Dawson & Jos Houben write: We last saw Jacques Lecoq in December last year. We visited him at his school in Rue du Faubourg, St Denis, during our run of Quatre Mains in Paris. We sat for some time in his office. His desk empty, bar the odd piece of paper and the telephone. On the walls – masks, old photos and a variety of statues and images of roosters. Dressed in his white tracksuit, that he wears to teach in, he greeted us with warmth and good humour. He was genuinely thrilled to hear of our show and embarked on all the possibilities of play that could be had only from the hands. No ego to show, just simply playful curiosity. He clearly had a lot of pleasure knowing that so many of his former students are out there inventing the work.

Later we watched the 'autocours'. This is where the students perform rehearsed impros in front of the entire school and Monsieur Lecoq. It was amazing to see his enthusiasm and kindness and to listen to his comments. He said exactly what was necessary, whether they wanted to hear it or not. He saw through their mistakes, and pointed at the essential theme on which they were working – 'water', apparently banal and simple. But there we saw the master and the work. Wherever the students came from and whatever their ambition, on that day they entered 'water'. Lecoq opened the door, they went in. They will never look at the sea the same way again and with these visions they might paint, sing, sculpt, dance or be a taxi driver. That was Jacques Lecoq.

Kenneth Rea writes: In the theatre, Lecoq was one of the great inspirations of our age. Not only did he show countless actors, directors and teachers, how the body could be more articulate; his innovative teaching was the catalyst that helped the world of mime enrich the mainstream of theatre. His techniques and research are now an essential part of the movement training in almost every British drama school. Thousands of actors have been touched by him without realising it.

As a teacher he was unsurpassed. Magically, he could set up an exercise or improvisation in such a way that students invariably seemed to do their best work in his presence. (Extract reprinted by permission from The Guardian, Obituaries, January 23 1999.)

H. Scott Heist writes: ‘You throw a ball in the air does it remain immobile for a moment or not? That is the question. Like Nijinski, the great dancer, did he remain suspended in air?’ These are the prepositions of Jacques Lecoq. Some training in physics provides my answer on the ball. But about Nijinski, having never seen him dance, I don't know. Remarkably, this sort of serious thought at Ecole Jacques Lecoq creates a physical freedom; a desire to remain mobile rather than intellectually frozen in mid air... What I like most about Jacques' school is that there is no fear in turning loose the imagination. As a matter of fact, one can see a clear joy in it.

Jon Potter writes: I attended Jacques Lecoq's school in Paris from 1986 to 1988, and although remarkably few words passed between us, he has had a profound and guiding influence on my life. For me, he was always a teacher, guiding the 'boat', as he called the school. I met him only once outside the school, when he came to the Edinburgh Festival to see a show I was in with Talking Pictures, and he was a friend – pleased to see and support the work.

He had a unique presence and a masterful sense of movement, even in his late sixties when he taught me. I remember him trying exercises, then stepping away saying, ‘Non, c'est pas ça.’ Then, finding the dynamic he was looking for, he would cry, ‘Ah, ça c'est mieux.’ His gift was for choosing exercises which brought wonderful moments of play and discovery. He had a special way of choosing words which stayed with you, and continue to reveal new truths. The phrase or command which he gave each student at the end of their second year, from which to create a performance, was beautifully chosen.

He taught us to make theatre for ourselves, through his system of 'autocours'. Every week we prepared work from a theme he chose, which he then watched and responded to on Fridays. He taught us accessible theatre; sometimes he would wonder if his ‘sister’ would understand the piece, and, if not, it needed to be clearer. He believed that everyone had ‘something to say’, and that when we found this our work would be good.

I feel privileged to have been taught by this gentlemanly man, who loved life and had so much to give that he left each of us with something special forever.

Shôn Dale-Jones & Stefanie Müller write: Jacques Lecoq's school in Paris was a fantastic place to spend two years. The training, the people, the place was all incredibly exciting. To meet and work with people from all over the world, talking in made-up French with bits of English thrown-in, trying to make a short piece of theatre every week. We thought the school was great and it taught us loads. And it wasn't only about theatre – it really was about helping us to be creative and imaginative. Its nice to have the opportunity to say thanks to him. He will always be a great reference point and someone attached to some very good memories.

Philippe Gaulier writes: Jacques Lecoq was doing his conference show, 'Toute Bouge' (Everything Moves). The show started, but suddenly what did we see, us and the entire audience? Lecoq had forgotten to do up his flies.

I was the first to go to the wings, waving my arms like a maniac, trying to explain the problem. My gesture was simple enough pointing insistently at the open fly. No reaction! I went back to my seat. Everybody said he hadn't understood because my pantomime talent was less than zero. Pierre Byland took over. He was much better than me at moving his arms and body around. No reaction! Lecoq's wife Fay decided to take over. Nothing! So she stayed in the wings waiting for the moment when he had to come off to get a special mask. When the moment came she said in French, with a slightly Scottish accent, ‘Jacques tu as oublié de boutonner ta braguette’ (Jacques, you for got to do up your flies). Problem resolved.

When Jacques Lecoq started to teach or to explain something it was just impossible to stop him. Nobody could do it, not even with a machine gun. And if a machine couldn't stop him, what chance had an open fly?

David Glass writes: Lecoq's death marks the passing of one of our greatest theatre teachers. If you look at theatre around the world now, probably forty percent of it is directly or indirectly influenced by him. He had a vision of the way the world is found in the body of the performer – the way that you imitate all the rhythms, music and emotion of the world around you, through your body.

In the presence of Lecoq you felt foolish, overawed, inspired and excited. His eyes on you were like a searchlight looking for your truths and exposing your fears and weaknesses.

His work on internal and external gesture and his work on architecture and how we are emotionally affected by space was some of the most pioneering work of the last twenty years. Perhaps Lecoq's greatest legacy is the way he freed the actor – he said it was ‘your play’ and ‘the play is dead without you’.

In a time that continually values what is external to the human being. Lecoq strove to reawaken our basic physical, emotional and imaginative values. Through his hugely influential teaching this work continues around the world.

Desmond Jones writes: Jacques Lecoq was a great man of the theatre. I cannot claim to be either a pupil or a disciple. I attended two short courses that he gave many years ago. In that brief time he opened up for me new ways of working that influenced my Decroux-based work profoundly.

Decroux is gold, Lecoq is pearls. It is right we mention them in the same breath. I did not know him well. I wish I had.

John Martin writes: At the end of two years inspiring, frustrating, gruelling and visionary years at his school, Jacques Lecoq gathered us together to say: ‘I have prepared you for a theatre which does not exist. Go out and create it!’

Thank you Jacques, you cleared, for many of us, the mists of frustration and confusion and showed us new possibilities to make our work dynamic, relevant to our lives and challengingly important in our culture. You changed the face of performance in the last half century through a network of students, colleagues, observers and admirers who have spread the work throughout the investigative and creative strata of the performing arts.

Lecoq was a visionary able to inspire those he worked with. He challenged existing ideas to forge new paths of creativity. But the most important element, which we forget at our peril, is that he was constantly changing, developing, researching, trying out new directions and setting new goals. He was not a grand master with a fixed methodology in which he drilled his disciples. He was a stimulator, an instigator constantly handing us new lenses through which to see the world of our creativity.

Workshop leaders around Europe teach the 'Lecoq Technique'. What a horror – as if it were a fixed and frozen entity. Fay Lecoq assures me that the school her husband founded and led will continue with a team of Lecoq-trained teachers. Theirs is an onerous task. The great danger is that ten years hence they will still be teaching what Lecoq was teaching in his last year. Teaching it well, no doubt, but not really following the man himself who would have entered the new millennium with leaps and bounds of the creative and poetic mind to find new challenges with which to confront his students and his admirers.

So next time you hear someone is teaching 'Lecoq's Method', remember that such things are a betrayal. What we have as our duty and, I hope, our joy is to carry on his work. Not mimicking it, but in our own way, moving searching, changing as he did to make our performance or our research and training pertinent, relevant, challenging and part of a living, not a stultifyingly nostalgic, culture.

“I have always had a dual aim in my work: one part of my interest is directed towards the Theatre, the other towards Life." – Jacques Lecoq

Carolina Valdes writes: The loss of Jacques Lecoq is the loss of a Master. The idea of not seeing him again is not that painful because his spirit, his way of understanding life, has permanently stayed with us.

Jacques Lecoq always seemed to me an impossible man to approach. I had the privilege to attend his classes in the last year that he fully taught and it always amazed me – his ability to make you feel completely ignored and then, afterwards, make you discover things about yourself that you never knew were there. That distance made him great. It was nice to think that you would never dare to sit at his table in Chez Jeannette to have a drink with him.

Monsieur Lecoq was remarkably dedicated to his school until the last minute and was touchingly honest about his illness. He was clear, direct and passionate with a, sometimes, disconcerting sense of humour. What he taught was niche, complex and extremely inspiring but he always, above all, desperately defended the small, simple things in life. He was essential.

Franco Cordelli writes: If you look at two parallel stories – Lecoq's and his contemporary Marcel Marceau’s – it is striking how their different approaches were in fact responses to the same question. Marceau chose to emphasise the aesthetic form, the 'art for art's sake', and stated that the artist's path was an individual, solitary quest for a perfection of art and style. Lecoq, in contrast, emphasised the social context as the main source of inspiration and enlightenment.

Lecoq never thought of the body as in any way separate from the context in which it existed. However, before Lecoq came to view the body as a vehicle of artistic expression, he had trained extensively as a sportsman, in particular in athletics and swimming. He became a physical education teacher but was previously also a physiotherapist.

But this kind of collaboration and continuous process of learning-relearning which was for Marceau barely a hypothesis, was for Lecoq the core of his philosophy. For him, the process is the journey, is the ‘arrival', the trophy. (Reproduced from Corriere della Sera with translation from the Italian by Sherdan Bramwell.)

Simon McBurney writes: Jacques Lecoq was a man of vision. He had the ability to see well. This vision was both radical and practical. As a young physiotherapist after the Second World War, he saw how a man with paralysis could organise his body in order to walk, and taught him to do so. To actors he showed how the great movements of nature correspond to the most intimate movements of human emotion. Like a gardener, he read not only the seasonal changes of his pupils, but seeded new ideas. During the 1968 student uprisings in Paris, the pupils asked to teach themselves. Thus began Lecoq's practice, ‘autocours’, which has remained central to his conception of the imaginative development and individual responsibility of the theatre artist.

Like an architect, his analysis of how the human body functions in space was linked directly to how we might deconstruct drama itself. Like a poet, he made us listen to individual words, before we even formed them into sentences, let alone plays.

What he offered in his school was, in a word, preparation of the body, of the voice, of the art of collaboration (which the theatre is the most extreme artistic representation of), and of the imagination. He was interested in creating a site to build on, not a finished edifice. Contrary to what people often think, he had no style to propose. He offered no solutions. He only posed questions.

Last year, when I saw him in his house in the Haute Savoie, under the shadow of Mont Blanc, to talk about a book we wished to make, he said with typical modesty: ‘I am nobody, I am only a neutral point through which you must pass in order to better articulate your own theatrical voice. I am only there to place obstacles in your path so you can find your own way round them.’ Among the pupils from almost every part of the world who have found their way round are Dario Fo, Ariane Mnouchkine in Paris, Julie Taymor (who directed The Lion King in New York), Yasmina Reza, who wrote Art, and Geoffrey Rush from Melboume (who won an Oscar for Shine).

Jacques was a man of extraordinary perspectives. But for him, perspective had nothing to do with distance. For him, there were no vanishing points. only clarity, diversity, and, supremely, co-existence. I can't thank you, but I see you surviving time, Jacques; longer than the ideas that others have about you. (Extract reprinted by permission from The Guardian, Obituaries, January 23 1999.)

"Believing or identifying oneself is not enough, one has to ACT." – Jacques Lecoq

Dick McCaw writes: September 1990, Glasgow. Pascale, Lecoq and I have been collecting materials for a two-week workshop – a project conducted by the Laboratory of Movement Studies which involves Grikor Belekian, Pascale and Jacques Lecoq. The big anxiety was: would he approve of the working spaces we had chosen for him? He arrives with Grikor and Fay, his wife, and we nervously walk to the space – the studios of the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama. He enters the studio and I swear he sniffs the space. He remains still for some while and then turns to look at me. ‘Parfait!’ And he leaves.

Later that evening I introduce him to Guinness and a friendship begins based on our appreciation of drink, food and the moving body.

Summer 1993, Montagny. He has invited me to stay at his house an hour's travel from Paris. We have been talking about doing a workshop together on Laughter. We plan to do it in his studios in Montagny in 1995. He takes me to the space: it is a symphony of wood – old beams in the roof and a sprung floor which is burnished orange. He beams with pleasure: ‘Tu vois mon espace!’ We looked at the communal kitchen and were already dreaming of a workshop, which would devote equal attention to eating and to working.

During dinner we puzzle over a phrase that Fay found difficult to translate: ‘Le geste c'est le depot d'une emotion.’ The key word is 'depot’ – deposit? depot? Jacques said he saw it as the process of accretion you find in the meander of a river, the slow layering of successive deposits of silt.

June 1998, Paris. I have been seeing him more regularly since he had taken ill. He insisted throughout his illness that he never felt ill – illness in his case wasn't a metaphor, it was a condition that demanded a sustained physical response on his part. I had asked Jacques to write something for our 10th Anniversary book and he was explaining why he had returned to the theme of Mime: ‘I know that we don't use the word any more, but it describes where we were in 1988. You know mime is something encoded in nature. If two twigs fall into the water they echo each other's movements.’

Fay asked if that was in his book (Le Corps Poetique). ‘No,’ he replied vaguely, ‘but don't you find it interesting?’

September 1998, on the phone. Jacques and I have a conversation on the phone – we speak for twenty minutes. This is the first time in ten years he's ever spoken to me on the phone, usually he greets me and then passes me to Fay with, ‘Je te passe ma femme.’ We talk about a project for 2001 – about the Body. Yes, that was something to look forward to: he would lead a 'rencontre'.

Jacques, you may not be with us in body but in every other way you will.

Joseph Alford writes: From the moment that I decided to go from University to theatre school, I was surprisingly unsurprised to know that L'Ecole Jacques Lecoq in Paris was the only place I wanted to go. The only pieces of theatre I had seen that truly inspired me had emerged from the teaching of this man. It is very rare, particularly in this day and age, to find a true master and teacher – someone who enables his students to see the infinite possibilities that lie before them, and to equip them with the tools to realise the incredible potential of those possibilities.

For me it is surely his words, ‘tout est possible’ that will drive me on along whichever path I choose to take, knowing that we are bound only by our selves, that whatever we do must come from us. Lecoq doesn't just teach theatre, he teaches a philosophy of life, which it is up to us to take or cast aside. I use the present tense as here is surely an example of someone who will go on living in the lives, work and hearts of those whose paths crossed with his. He is a truly great and remarkable man who once accused me of being ‘un touriste dans mon ecole’, and for that I warmly thank him.

Allison Cologna and Catherine Marmier write: Those of us lucky enough to have trained with this brilliant theatre practitioner and teacher at his school in Paris sense the enormity of this great loss to the theatrical world. His influence is wider reaching and more profound than he was ever really given credit for.

In many press reviews and articles concerning Jacques Lecoq he has been described as a clown teacher, a mime teacher, a teacher of improvisation and many other limited representations. All these elements were incorporated into his teaching but they sprung from a deeply considered philosophy. He was equally passionate about the emotional extremes of tragedy and melodrama as he was about the ridiculous world of the clown. He saw them as a means of expression not as a means to an end.

It would be pretentious of us to assume a knowledge of what lay at the heart of his theories on performance, but to hazard a guess, it could be that he saw the actor above all as the creator and not just as an interpreter. He provoked and teased the creative doors of his students open, allowing them to find a theatrical world and language unique to them.

Shortly before leaving the school in 1990, our entire year was gathered together for a farewell chat. Many things were said during this nicely informal meeting. But one thing sticks in the mind above all others: ‘You'll only really understand what you've learnt here five years after leaving,’ M. Lecoq told us. We were all rather baffled by this claim and looked forward to solving the five-year mystery. We then bid our farewells and went our separate ways. People from our years embarked on various projects, whilst we founded Brouhaha and started touring our shows internationally. When five years eventually passed, Brouhaha found themselves on a stage in Morelia, Mexico in front of an extraordinarily lively and ecstatic audience, performing a purely visual show called Fish Soup, made with £70 in an unemployment centre in Hammersmith. Did we fully understand the school? It's probably the closest we'll get. Thank you Jacques Lecoq, and rest in peace.

Bim Mason writes: In 1982 Jacques Lecoq was invited by the Arts Council to teach the British Summer School of Mime. I was very fortunate to be able to attend; after three years of constant rehearsing and touring my work had grown stale. During the fortnight of the course it all became clear the job of the actor was action and within that there were infinite possibilities to explore. From then on every performance of every show could be one of research rather than repetition. The excitement this gave me deepened when I went to Lecoq's school the following year. I was able to rediscover the world afresh; even the simple action of walking became a meditation on the dynamics of movement. ‘Toute Bouge' (Everything Moves), the title of Lecoq's lecture demonstration, is an obvious statement, yet from his point of view all phenomena provided an endless source of material and inspiration.

Observation of real life as the main thrust of drama training is not original but to include all of the natural world was. His Laboratoire d'Etude du Mouvement attempted to objectify the subjective by comparing and analysing the effects that colour and space had on the spectators.

This process was not some academic exercise, an intellectual sophistication, but on the contrary a stripping away of superficialities and externals – ‘the maximum effect with the minimum effort', finding those deeper truths that everyone can relate to. This was blue-sky research, the NASA of the theatre world, in pursuit of the ‘theatre of the future'. He pushed back the boundaries between theatrical styles and discovered hidden links between them, opening up vast tracts of possibilities, giving students a map but, by not prescribing on matters of taste or content, he allowed them plenty of scope for making their own discoveries and setting their own destinations

Unfortunately the depth and breadth of this work was not manifested in the work of new companies of ex-students who understandably tended to use the more easily exportable methods as they strived to establish themselves and this led to a misunderstanding that his teaching was more about effect than substance. However, it is undeniable that Lecoq's influence has transformed the teaching of theatre in Britain and all over the world if not theatre itself. He has shifted the balance of responsibility for creativity back to the actors, a creativity that is born out of the interactions within a group rather than the solitary author or director. The fact that this shift in attitude is hardly noticeable is because of its widespread acceptance.

Among his many other achievements are the revival of masks in Western theatre, the invention of the Buffoon style (very relevant to contemporary culture) and the revitalisation of a declining popular form – clowns. He was certainly a man of vision and truly awesome as a teacher. His legacy will become apparent in the decades to come.

“In life I want students to be alive, and on stage I want them to be artists." – Jacques Lecoq

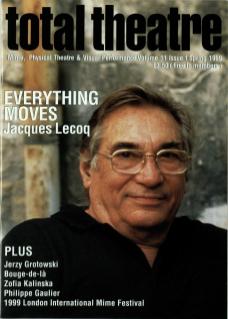

All quotes from Jacques Lecoq are taken from his book Le Corps Poetique, with translation from the French by Jennifer M. Walpole. Special thanks to Madame Fay Lecoq for her assistance in compiling this tribute and to H. Scott Helst for providing the photos.