It is a Friday morning, and I'm in a cafe in Sheffield – the first time in my week with the CircElation project that I have been by myself. Since my arrival last Sunday, days and nights have been filled with workshops, discussions, video showings, talks from guest speakers. The scheduled sessions have been supplemented by animated late-night talks with my temporary flatmates – tutors Gail Kelly and Kathryn Hunter – on anything from the dramaturgy of circus to the role of the writer in physical and visual performance.

Sitting in the cafe, I glance at the full notebook that contains the observations, thoughts and responses to the week. From one of the opening sessions, there is a comment from a participant that her aim is to find the 'honest reason' for wanting to integrate circus and theatre. Others express a desire to explore and play, to 'break the logic and to be touched'. People want to learn how to incorporate skills into concepts, and some hope to meet people they could work with in the future, to 'break the isolation of the circus performer united only with their trick’.

Now, at the tail end of the week, there is an afternoon of presentations by those who felt that they wanted to show some of their working processes to the others. We are holding these presentations at a series of venues throughout the city. The first destination is the Burton Street community centre in Hillsborough, where location scenes for The Full Monty were shot. Inside the centre, Gail greets us with 'Welcome to our process’ and explains that this part of the presentation will consist of a witnessed warm-up, a series of duets worked on by trainee directors and performers, and a group piece.

The starting point for the work is the phrase 'caught between the moment and the form', most poignantly expressed in a piece called Jess Learns to Fly, which grasps the essence of the clown's desire for love and glory juxtaposed with the reality of life's pain and limitations. The group piece takes place in a room with many doors and windows, fully exploited in a performance that uses sound and vision to create a compelling narrative. Slamming doors, crashing coils of heavy rope, footsteps, fists – the rope and doors become living things, engaging with the performers, thwarting them, confronting their desires and fears.

We move on to another venue for the next part of the afternoon – a presentation from a group which has worked with site-specific director Ron Bunzl. The Compass Theatre, in contrast to the school hall feel of the community centre, is an old lady of the theatre. Balustrades, wooden staircases and mirrors create an atmosphere of Victorian music hall decadence. It feels as if the ghosts of old performers haunt every nook and cranny of the building, a notion exploited fully by the group, who have decided to present a ‘proper circus show'.

Every cliché in the vocabulary of circus and variety is reinvented, every metaphor is explored: the broken-hearted clown is scored by the pretty trapeze artist; the jolly impresario in loud suit wins the heart of the lovely lady singer in evening gown; the merry clown plays the trumpet and the trickster grins and gurns. Like any circus or variety show, we are given a series of tricks and turns to marvel at – but tangled into a subversion of the form. The result is a dark and surreal cabaret in which, for example, a confessing priest crashing from a balustrade and a glamorous housewife washing up in her party frock become linked in a suggestion of guilt and absolution.

For the final part of the presentations we move onto Forced Entertainment's Workstation studio. Here we see choreographer Phillip McKenzie's group, who have created a piece that combines movement theatre with object manipulation and video projection of aerial work recorded the previous day at Greentop Community Circus. The strength of the ensemble work is such that it is hard to believe that the group has been together for only a week. The previous Sunday's introductory gathering now feels a long time away.

That gathering, at the very start of the project, had understandably brought up many different hopes, fears and anxieties about the coming week. There was, of course, an air of expectation and a desire to engage with the new possibilities offered, but also concerns that approaching things in a different way would be a challenge. One of the big worries was that not all of the workshop spaces were riggable – a blow to some of the aerialists present. The project's artistic director Deborah Pope had spent a lot of the session reassuring those concerned that it would be possible to rig in some spaces, but she also expressed her feeling that people should be willing to let go of their 'safety blankets' – their known skills – in order to find other ways of working.

This turned out to be an oft-repeated mantra throughout the week. Tutor Gail Kelly, an Australian director with years of experience with many different companies from Circus Oz to Club Swing, was insistent in her opening session that the work must start with an engagement with the ground and an awareness of the space as a three-dimensional frame. Only then could the crucial relationship between ground and air be explored.

For choreographer Phillip McKenzie, creating a physical landscape was at the heart of the exploration. His group worked on ways of navigating a space – walking, weaving, flocking, dispersing. They were urged to compose as an ensemble using the whole space, to explore the possibilities of speed and stillness, to take the offers given in the improvisations, to use each other as part of that landscape. The group was a mixture of people familiar with contemporary dance practices and those with other backgrounds, producing a fascinating physical dynamic.

"Allow the stillness to tell you what to do.”

The hardest lesson for everyone was to learn that less is more – to allow the stillness to tell you what to do. For both circus artists and dancers, motion is at the heart of their practice. Yet without the contrasting stillness, the motion is lost in a sea of movement. An analogy could be drawn to music; silence and sound need each other to create music – movement and stillness need each other to create physical performance.

A third group of participants worked with Kathryn Hunter of Theatre de Complicite, exploring ways of storytelling in physical performance. Her group worked on an exhilarating mix of exercises and devising tools – physical and vocal call and response; merging movement motifs with object manipulation; exploring states of tension; using the chorus in collective storytelling. 'Serving the group' was a notion that many participants struggled with – particularly if a character attribute was added to the individuals who made up a chorus. What had worked well when delivered in neutral mode was suddenly a struggle to maintain.

For many performers wanting to move into work that bridges the forms of circus and theatre, the problem of integrating character into the physical circus skill is something that presents an enormous challenge. Some participants had spoken of their experiences in circus-theatre shows, expressing a concern that the work often veered between the two forms rather than being something that fused them both. One way to avoid the tacking-on of narrative to circus tricks would be to choose, as Kathryn put it, to 'develop the story from the spatial attitudes'. Like Gail and Phillip, she also urged the workshop participants to allow the space to tell the story. On the subject of constructing a character, she offered a series of questions for would-be devisers to work with: Where have I come from? Where am going? What do I want? What are my obstacles? What are my tactics? By the end of the week, many members of the group felt far more confident with the integration of different sorts of performance skills.

Ron Bunzl, a site-specific director from the Netherlands, also explored character in his workshop sessions – but in a rather different way. He sent his group out on to the streets to find a real-life character to observe and absorb. Participants were urged to avoid the obvious and avoid caricature; to really take in the physical information on offer from the person observed – how do they move, react to other people and interact with objects? On returning to the theatre, the group presented their characters – individually then collectively. The use of entrance and exit was explored, as well as learning to respond to every offered possibility: the whole available space, the other people in the space and the objects within that space.

Another exploration was the ‘party trick', Ron giving the directive for the participants to present something of themselves to the audience, aiming to give a sense of enormous expectation to a simple act. The 'acts' that followed were an eclectic mix of the surreally banal and the plain bizarre. A struck match, a bra magically removed from under a jumper, a gargled song – whatever the trick it had to be delivered as if it was the most unique and extraordinary happening in the world. Each performer was urged to make more of it, to persuade the audience not to suspend disbelief but to really believe. By really engaging with the physicality of the object they were working with, each performer could celebrate the reality of the thing they were doing. This, Ron felt, is at the essence of circus – the belief in what is real conveyed from performer to audience.

This notion of the reality of circus, in contrast to some forms of theatre that celebrate the illusory, was something that emerged in many ways in the evening discussions, which included a Total Theatre Network critical practice debate as part of the week's events. (See report on page 19.) In that discussion, Reg Bolton spoke of the spectrum of belief: from total suspension of disbelief through to total belief.

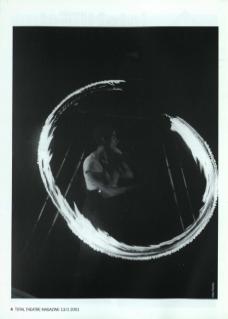

In another of the evening discussions, Bim Mason from Circomedia spoke of circus as 'something essential and true'. Later in the week, Rose English reflected this thought when she referred to ‘the Spirit of La Verdad (the truth)'. Her talk started with the claim that circus was seductive, cerebral and synaptic. Like one of the week's other guests, former ringmaster turned manager Chris Barltrop, she had an enduring love for the traditional circus act. The fact that people spend a lifetime learning skills that take a nano-moment to perform was proof to her that circus skills, indeed circus itself, is on a 'cosmological sphere’ – the perfect metaphor for life itself. Nothing lasts, everything changes, the deepest things are short-lived.

For many people, including participant Pete Turner, authenticity is at the heart of circus. The challenge is to retain that authenticity, that engagement with the heart of humanity whilst moving the work on to new collaborations and investigations. It is a challenge that will continue to be addressed in the ongoing CircElation project. Perhaps we could take as our inspiration the text used by Gail Kelly at the start of her week's work: ‘We now take for granted that reality is not what it seems and that at any moment a trapdoor may open without warning and drop us into our unconscious.'

CircElation is a professional training and development project organised by BhathenaJancovich.