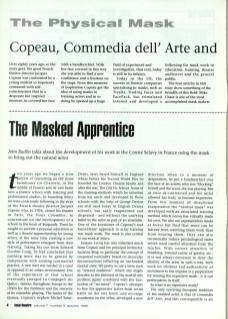

Two years ago we began a slow process of converting an old stone farmhouse (in Charente, in the middle of France) and its vast barns into a theatre school with training and performance studios. In founding Sélavy we were consciously following in the steps of the French theatre director Jacques Copeau who, in 1924, closed his theatre in Paris, the Vieux Colombier, to concentrate on the development of a school in the heart of Burgundy. There he sought to provide a personal education as well as a theatre apprenticeship for young actors, at the same time creating a new style of performance emergent from their training. Taking his cue from Edward Gordon Craig, he had concluded that nothing more was to be gained by compromise with existing commercial practice. A new start was needed in a rural as opposed to an urban environment. Out of the experiment of that school eventually emerged La Compagnie des Quinze – famous throughout Europe in the 1930s for the freshness and the sincerity of its ensemble playing. The leader of the Quinze, Copeau's nephew Michel Saint-Denis, later based himself in England where before the Second World War he founded the London Theatre Studio and after the war, The Old Vic School. Some of the training methods which he inherited from his uncle and developed in these schools with the help of George Devine are still used today in English Drama schools, but sadly fragmented and dispersed – and without the unifying belief in the actor as part of an ensemble. One of the keystones of Copeau's and Saint-Denis' approach to actor training was mask work. The mask is also central to our work at Sélavy.

Jacques Lecoq has also inherited much from Copeau and his principal instructor, Suzanne Bing; in particular the concept of corporeal neutrality based on muscular decontractions reflecting an unclouded mental state. We prefer to use a term such as ‘relaxed readiness’, which one might describe as the alertness of the martial arts position jigotai combined with the Zen notion of ‘no-mind’. Copeau's attempts to free his apprentice actors from social habit on the one hand, and on-stage woodenness on the other, developed a new direction when in a moment of desperation, he put a handkerchief over the face of an actress who was ‘blocking’ herself and the scene she was playing. She at once decontracted and her mind allowed her body to become expressive. From this moment of directional exasperation the 'neutral mask' was developed with an associated training method which Lecoq has virtually made his own. We also use expressionless masks at Sélavy but find that more can be learned from watching them work than from wearing them. They can also occasionally induce psychological states which need careful attention from the teacher. With correct attention to breathing, lowered centre of gravity, etc, it is not always necessary to deny the identity of the actor in such a way. Such work on stillness and authenticity of movement to the impulse is a preparation for wearing the expressive mask – it is not performative in itself.

So what is an expressive mask?

The only surviving European tradition of the masked actor is that of Commedia dell' Arte, and this consequently is an important discipline within our training at Sélavy.

The half-masks of the fixed personae of Commedia are made of leather and the actor has to learn to adapt the muscles of the lower part of the face to form shapes which complement the traditional, immutable shapes above. Again, therefore, we are investigating an acting process which is contradictory to the personal emotional approach of the Stanislavski system. This is not to say that Commedia cannot achieve extreme emotional states – but only through the mastery of the form and shared technique. And that technique begins and ends with the mask. However, in Peter Brook's terminology, Commedia is definitely a ‘rough’ form and its Masks (as its fixed characters should be properly called) cannot achieve the ‘holy’. The European mask-form which did, Greek Tragedy, has not been preserved.

Masked performance styles invented to bridge this gap tend to feel arch to the European spectator used to searching the actor’s face for emotive signals. Footsbarn is one of the few contemporary companies to have developed a masked performance style that does not seem artificial and is capable of dealing with Shakespearean Tragedy as well as Comedy. Their roots are also in Copeau and in the half-masks of Commedia. One of the quests in the Sélavy School, as with those of Copeau, Saint-Denis and Lecoq, is for a European equivalent of the medieval Japanese Noh: a full mask form which although highly artificial, can convey theatrical meaning in an authentic rather than a contrived way.

In the mirror room before the performance the actor contemplates the mask. In a sense it also contemplates him. Then, through the ritual of putting on the mask, the actor also puts his own face down. This communion of face and mask is then carried to the audience who similarly are given time, through the medium of the actor and his technique, to discover its essence or ‘flower’ as it is called.

In the Autumn term at Sélavy we will be concentrating on medieval forms, seeking through them an expressive dynamic consistent with the rural environment in which we are working. Renaissance and post-Renaissance forms tend to stress the urban and the urbane, whereas, for example, the portals, corbels and gargoyles of our local Romanesque churches were made by the master-craftsmen who had an uncomplicated approach to their means of expression. Our masks will be based on their forms, which include the bizarre, the grotesque, the hideous and the beatific. The next quest will be to transmogrify stone into movement, stasis into live performance.

Centre Sélavy was founded in 1994 by John Rudlin (drama teacher, director and author), Amanda Speed (actor, drama teacher and mask-maker), and Alison Kennedy (actor, community animateur and teacher of French). Centre Sélavy, Grosbout, 16240, La Foret de Tesse, France.