Beckett's Act Without Words I, written as a score of physical actions, contains the line: 'Does not move.' How can we physically act 'Does not move'? What do we do, if we don't move? But this is specifically written as a separate action, so it must be performed as an action. Watching international director and teacher Phillip Zarrilli performing Act Without Words I, there is a clear moment when he is lying on the floor where he communicates: 'Does not move'. He explains that he achieves this through focusing on the breath, keeping his awareness through his feet, hands, eyes and ears, and the clear thought of the line itself. He needs to fill in the white space of the moment, to embody the thought, feeling and action of the decision to not move. Although there is no outer movement, he appears to express a clear inner choice: 'Does not move'. It is through the connection with the bodymind and the breath, states Zarrilli, that 'thought takes shape as action', even if the action is to remain still.

Zarrilli has been developing a unique psychophysical approach to actor training and performance for over 25 years. He utilises a selection of Asian cultivation practices: yoga, tai chi chuan, and the fast and flowing south Indian martial form of Kalaripayattu. He has trained in, and written extensively about, kalaripayattu and the Indian dance-drama form of kathakali since 1976. It might well be asked, how can a form as dynamic as kalaripayattu be of use to an actor in performing Beckett, where they are often so physically restricted? If there needs to be stillness, of what help is the flow of movement and energy in martial arts? It is this very need for outer stillness, but a stillness filled with 'inner life', that Zarrilli states makes his training so relevant for Beckett. He quotes the late A.C. Scott's phrase relating to tai chi, the need to 'stand still while not standing still’. Even though there may be little movement externally, the bodymind needs to be filled out from the inside to keep the performer engaged with the action, and give life to the moment of performance.

Yoga and martial arts have been used in actor training for many years. Stanislavski adapted exercises from yoga for use with actors in the First Studio at the Moscow Art Theatre from 1912. His use of Eastern practices has influenced many key practitioners since, including Michael Chekhov, Jerzy Grotowski, and Eugenio Barba. Training in yoga and tai chi is now not uncommon in drama schools in Britain and America. However, these forms of training are often used as preparatory exercises to relax and focus the actor, and are practised in isolation to rehearsals. They become a warm-up, something useful for the opening of a session, but not of real relevance to the western actor in the context of rehearsing a play. What makes Zarrilli so significant is that his use of martial arts goes beyond an initial training period, and has direct importance in not only the embodiment of the actor in performance but also, in the case of Beckett, in an enhanced understanding of the dramaturgy of the play, and how this can be actualised.

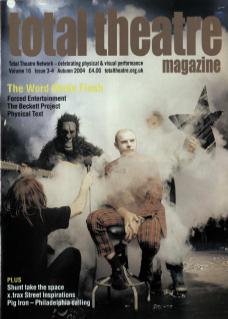

This was demonstrated in 'The Beckett Project in Ireland', which took place in May 2004 in Cork, and consisted of the performance of seven of Beckett's short plays:

Ohio Impromptu, Play, Eh Joe, Not I, Footfalls, Act Without Words I, and Rockaby. They were performed by a company of six actors, including the renowned American actress Patricia Boyette, and directed by Zarrilli. The actors had begun the rehearsal period with one week of intensive training with Zarrilli in the forms he teaches, after which the rehearsals were preceded by one and half hours of training every day. Even though some of the actors had worked with Zarrilli before, it is clearly not possible for them to be able to fully learn the forms in a few weeks. When Zarrilli teaches in a university context, there is a one- or two-year training programme, during which time students can begin to have a deeper understanding and embodiment of the techniques. With a much shorter time in which to work, Zarrilli focuses on the ways in which the cultivation of the bodymind through the forms can be of benefit for the actor. The forms all focus fundamentally on the breath, and a development of awareness, concentration, grounding and a sense of 'interiority' which is actualised in outer movement, thus connecting inner and outer in such a way that can lead to complete embodiment of the performative action in each moment.

Zarrilli explains that when directing or performing, his point of entry into a particular dramaturgy is through 'problem-solving' using psychophysical approaches. This includes the basic principles from the training, such as control of the breath, awareness, grounding and focus, but also finding the specific demands for each play. In Footfalls, the character of May, played in The Beckett Project by Bernadette Cronin, repeatedly turns and walks in a set number of steps. In order to fully embody this action throughout the play, she needs to retain a sensory awareness in the act of walking, and in rehearsal learned to focus her attention on her feet. When not walking, her spoken text is describing her steps, so she needs to keep this awareness in her feet through her voice, creating a resonance of the movement which can help to embody the text.

This application of psychophysical approaches to the voice is particularly important in Beckett. Billie Whitelaw, a long-term collaborator with Beckett, has discussed the importance of using 'no colour' in approaching his texts. Rather than having a psychological notion of the idea of a 'character', the focus instead should be on the musicality and rhythm of the text. This is especially difficult for performers who are used to attempting to be as expressive as possible. However, within Beckett the problem for actors is the necessity of cutting away all unnecessary movement and vocal expression. But this does not mean that the voice is 'empty' or monotone: the task is again how to find the fullness within the 'no colour'. Patricia Boyette needed to find this for herself whilst playing the Voice in Eh Joe. Whitelaw, whom Boyette has consulted several times, suggested that she feel her voice as being like 'Chinese water torture', each phrase being a drip of water in Joe's head. Zarrilli additionally suggested she could sense that each phrase is a sewing needle going under and through the skin. Zarrilli, playing Joe, responded to the sound of Boyette's Voice through a series of psychophysical devices. The text states that Joe wants to ‘squeeze' the voice out of his head, and Zarrilli tries to suggest this 'squeezing' by listening to the voice whilst not blinking. This is physically very difficult, and Zarrilli achieves it by feeling his feet on the floor, and connecting this with his breath, and then putting his awareness into his lower eyelids, which helps stop his eyes from blinking. Since this is physically exhausting, the release of his breath each time the Voice stops speaking is directly communicated to the audience. I found Zarrilli's performance of Joe to be extremely affecting, with the sewing-needle metaphor made very real: each time the Voice began speaking, I felt as if a just-healed scar was being scratched open.

While watching all seven plays, I had this same physical, visceral response to each piece. Boyette, in particular, gave stunning performances of the immensely difficult and taxing Not I and Rockaby. Whitelaw had told her that she needed to find an individual voice for each part, and through using a psychophysical exploration of resonance in different parts of the body, she certainly offered very distinctive vocal qualities in her three performances, each with different shadings of 'no colour'. Overall, even though the actors were not necessarily overtly 'doing' much, the intensity of their inner connection and involvement was very present.

The means used to produce the performance is itself not obvious on stage. The audience need have no knowledge of the inner processes of the actor in actualising each moment, nor of the intense training methods that have led them to cultivating it, in order to feel their presence. This is another important factor in the use of Zarrilli's work, in that the actor can use concrete tools and devices to find complete embodiment in the action of the play, which remain 'invisible' to the audience who only need to see that which is relevant for the dramaturgy. Having seen The Beckett Project in Ireland, I feel that even after a short period of experience of the martial arts training and methods that Zarrilli uses, there is a possibility for finding the resonance, rhythm, musicality and 'no colour' in Beckett's work through a psychophysical exploration of performance that fills each action with inner life, and enables the performer to stand still, while not standing still.

Phillip Zarrilli directs and teaches workshops internationally. He is also Professor of Drama at Exeter University, and offers training at his studio in west Wales. See www.ex.ac.uk/drama/staff/kalari