Dorothy Max Prior reflects on the fabulous selection of puppetry and object theatre shows being presented at London International Mime Festival 2020

Puppetry has come a long way. In these post-War Horse days, you’d be hard pushed to find an adult theatre-goer who considered puppets to be mere child’s play, and the inclusion of puppetry within the broad church of physical and visual theatre practice has become an accepted norm. From Complicite to Kneehigh, Improbable to Emergency Exit Arts, puppets and animated objects can be seen providing a crucial element of the scenography and storytelling of UK companies in our theatres, opera houses, and outdoor arts festivals.

But many might be surprised to learn of the extraordinary range of work presented under the puppetry umbrella. In the 2020 edition of London International Mime Festival (LIMF), which runs from 8 January to 2 February in various venues across the capital, no less than six of the eighteen shows on offer feature puppetry, animation or object theatre – and it is hard to imagine six more different shows!

These shows come from all over the world, showcasing the diversity of contemporary puppetry practice: all puppet life is here. UK based String Theatre use traditional long-string marionette puppetry, with the manipulators out of sight, to tell the treasured tale of The Water Babies; whereas in Tria Fata, French company La Pendue mix and match puppeteering, live music, and physical action, creating a swirling kaleidoscope of imagery in a contemporary take on Greek mythology. In Chimpanzee, American artist Nick Lehane uses bunraku inspired table-top puppetry to tell a heartbreaking story (based on real accounts of human-chimpanzee interaction) of an animal raised in a human family, then imprisoned in a biomedical facility; whilst Opposable Thumb (UK) offers a subversive mix of slapstick, mime, puppetry, existential angst and big shoes in Coulrophobia. At the more esoteric end of puppetry practice is Kiss & Cry Collective from Belgium, whose Cold Blood brings us the story of seven surprising deaths, using intricate hand choreography, beautifully constructed miniature sets, and live-feed video; and Australia’s Fleur Elise Noble gives us ROOMAN, a surreal love story blending puppetry, projection and live performance into something resembling an animated graphic novel.

What this broad range of shows have in common is a belief in the power of visual storytelling. Take Chimpanzee, for example. This extraordinary piece of work was inspired by Roger Fouts’ book Next of Kin: My Conversations with Chimpanzees, and tells the story – wordlessly – of a chimpanzee who escapes the despair of her captive existence in a biomedical facility by piecing together memories of her childhood in a human home.

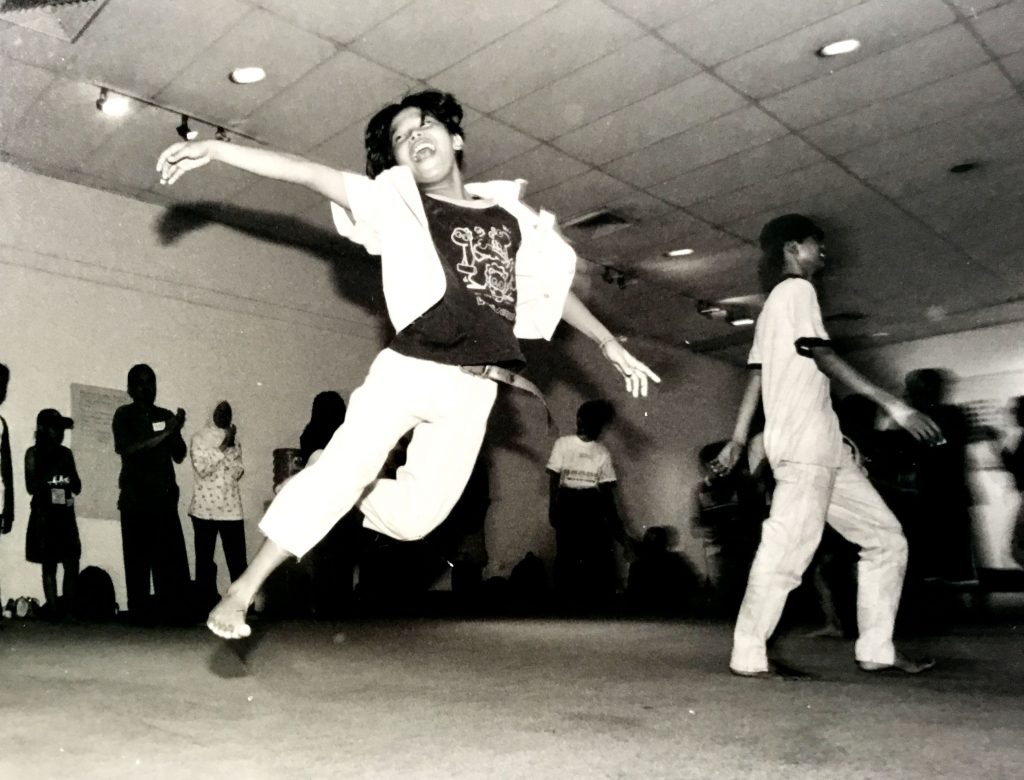

Nick Lehane: Chimpanzee. Photo Richard Termine

The show’s writer/creator Nick Lehane is very clear that it needed to be a word-free piece:

‘It was always my intention to use no vocalised language. It’s often how I prefer to work in puppetry, but it was particularly important for this play. I wanted to make a piece with a non-human animal at the absolute centre, as the unmistakable protagonist, with the show entirely from her perspective… I was interested in how much could be created strictly through a puppet and a soundscape. The power of puppetry is in the empathetic, imaginative leap the audience makes to believe the object is a living, breathing being. I wanted to take full advantage of that powerful pact with the audience in a show that hopes to widen the circle of empathy.’

The show was developed through The Puppet Lab at St Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn New York, and both financially supported and heartily endorsed by the Henson Foundation. Cheryl Henson, daughter of the legendary Muppets creator Jim Henson, has made the promotion of the show a personal mission, ceaselessly campaigning for European festivals to programme the work, following its phenomenal success in North America. ‘The Henson Foundation and Cheryl Henson have supported Chimpanzee at every step of it’s development’ says Nick. ‘None of this would have been possible without their unwavering commitment to this piece.’

Talking of the scenography of the piece, Nick says:

‘The world the chimpanzee lives in is largely sonic and light based, as well as centred around special nostalgic objects. When she’s in the present – in the cage – she interacts with the floor as literal space. In memory, miming techniques are used for her to interact with invisible architecture and move across expansive spaces without leaving the confined table top.’

The crucial sound design is by Kate Marvin, with lighting design by Marika Kent and Ayumu Poe Saegusa. The chimpanzee puppet at the heart of the piece is described by Nick as ‘a pretty simple object. Her insides are wood and cord. Her body is mostly carved white bead-foam, and her outside is papier-mâché. She’s a table top puppet – a style that that was inspired by the Japanese bunraku tradition.’ And as is usually the case with bunraku-inspired work, she is animated by a trio of puppeteers – the human beings on stage are there as operators, not characters.

La Pendue: Tria Fata. Photo Tomas Vimmr

In La Pendue’s Tria Fata there is a very different onstage set-up. The piece – inspired by the myth of the The Three Fates, who spin the thread of life, and decide when it will be cut – is performed by Estelle Charlier and Martin Kaspar Läuchli, a puppeteer and a musician – although it wasn’t quite this simple to start with.

Romuald Collinet, co-founder of the company (with Estelle Charlier), explains:

‘Our starting point was for Estelle and I to work together to build some visual ideas, using puppetry to explore the symbolism of strings; and the themes of life and death. After five years of rehearsal, we had three or four hours of material cut into several versions, using musicians, actors, and puppeteers… So we tried to find a simple version for one puppeteer and one musician. We were less interested in staying true to the myth than in provoking emotions with our ideas; exploring the mystery of life through one character – an old lady on the edge between life and death. It’s food for the collective unconscious – poetry with a popular sauce.’

The food analogies linger, as speaking of the mix of forms used in the piece – which include movement, mask, puppetry of various kinds, and live music –Romuald adds: ‘Think of it as the ingredients for good cooking!’

The collaboration and complicity between puppeteer-performer Estelle Charlier and musician Martin Kaspar Lauchli (who creates the delicious soundscape using clarinet, accordion, drums and voice) is described by Romuald simply as ‘Love!’.

On their website, La Pendue state a desire ‘to defend puppetry as a universal human symbol able to reveal dark zones, to alter social masks, and to guide the spectator toward his inner self’. Romuald elucidates:

‘An actor has limits that the puppet doesn’t have, and a puppet has limits that the actor doesn’t have. But the puppet is empty… It does not sweat, does not sing, does not live, and does not die. The puppet does nothing but be, or not be, without asking the famous question. It is not even a historical jester’s skull. The puppet is nothing. It is only what the public accepts it to be. The puppet is empty of ego and empty of soul… If the puppet is well employed (using aesthetics, technique, words, manipulation, emotion, etc.) then the spectator identifies with it, and fills it with his personal projections and perhaps, we believe, fills it with his soul. Then the puppet becomes an emotional vector of great power.’

For La Pendue, who trained and met at France’s renowned national puppetry school at Charleville Mezieres, there is no question of whether to use puppetry or not: ‘We are first puppeteers, secondly actors. We think puppets. That’s how it is.’

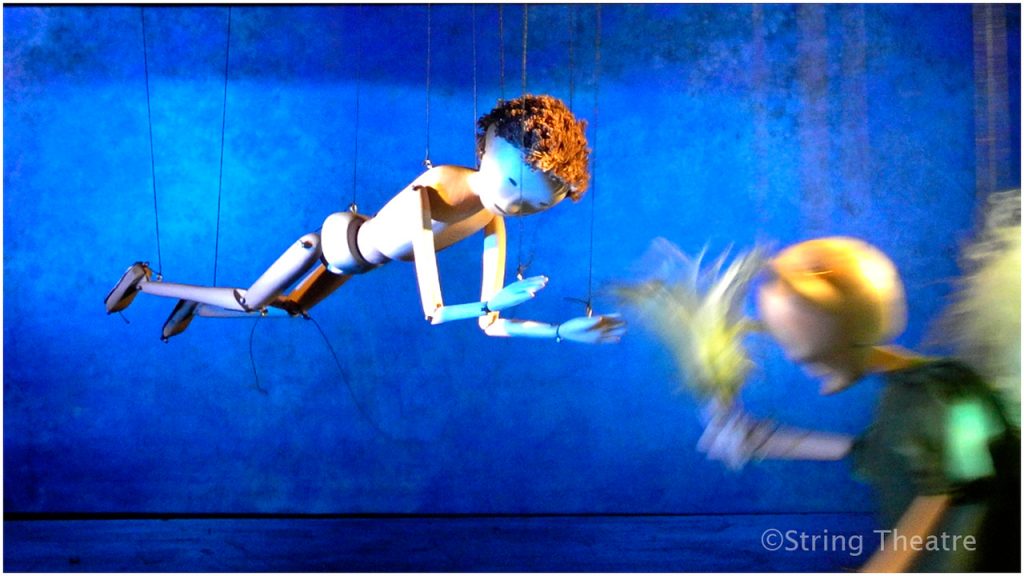

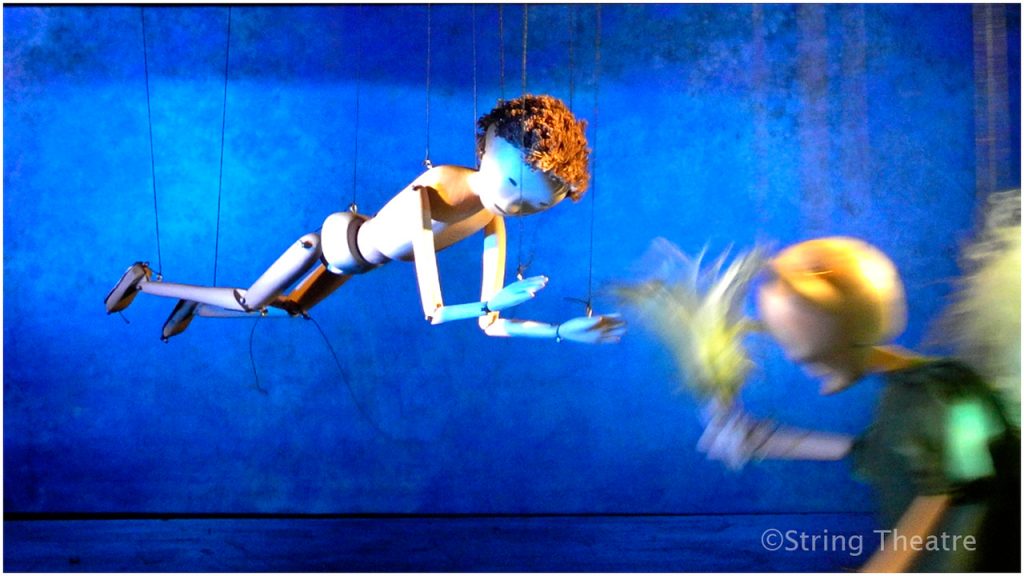

String Theatre: The Water Babies

Also totally steeped in the puppetry world are String Theatre, which was formed by third-generation marionettist Stan Middleton, whose family run London’s famous Puppet Theatre Barge; and Soledad Zarate, from Argentina. Soledad reflects on how the company was formed:

‘I met Stan at the Puppet Theatre Barge, where I trained to become a marionettist in 2007. Stan was working with his grandparents and mother in the first marionette production I got involved in as a trainee, The Ancient Mariner by Coleridge. At the end of the traineeship, I created a short shadow piece based on The Red Balloon, the French silent film of 1956 by Lamorisse and Stan helped me…’

So both Stan and Soledad are used to using pre-existing works – books or films – as a starting point. But why, in particular, Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies?

‘I wasn’t brought up in England, so I came across the book as an adult,’ says Soledad. ‘I’m fascinated by stories set in Victorian times, and when I finished the book I could not think of a better story for the marionette stage. There are elements in the book that can be expressed particularly well with marionettes. After Tom, the little chimney sweep, transforms into a water baby, the possibilities are endless.’

The main form used, as the company’s name suggests, is long-string marionettes – but shadow puppetry also plays a part:

‘When Tom escapes from his cruel master Mr Grimes, there is a fast-paced chase scene amid rooftops and trees. With the use of light, we are able to convey the journey that leads Tom to his water life.’

The Water Babies is a word-free piece in which the music composition and sound design is a vital element. The composer is Jimmy Sheals and the puppeteers worked very closely with him:

‘He attended rehearsals so that he could see the puppets in action and get an understanding of what we wanted to achieve. It was a very easy process of mutual understanding where I feel that the musician greatly contributed to the artistic value of the show.’

String Theatre have so far made four marionette productions and in all of them, the operators are out of view. Soledad explains why:

‘The idea is to create a space where the audiences can be transported and their imaginations sparked. The lack of human presence on stage allows us to create a world where perspective and lighting can be used to represent something in the distance, for example. By losing the human reference, the focus is exclusively on the puppets, which are our only and main characters.’

Opposable Thumb: Coulrophobia. Photo Adam Laity

At the other end of the spectrum, with its in-your-face human performers, is Opposable Thumb’s Coulrophobia (fear of clowns). It’s a subversive clown and object theatre show performed by the company’s founders Dik Downey and Adam Blake, who are directed by John Nicholson (of Peepolykus fame). It is in some ways a classic two-man clown relationship, built on the performers’ own individual characteristics and foibles, says Dik Downey:

‘Adam and I discovered that we were a pretty good team whilst working on The Shop of Little Horrors [for Dik’s previous company, Pickled Image].Our characters accidentally reflected us in life – Adam young and keen, me old and grumpy – but together we seemed to bring out the best in each other. Once we decided that we were going to make a new show, we knew we were going to play on our differing characteristics, exaggerating them to comic extremes. I knew John from seeing Peepolykus shows since the mid 1990s. I really love John’s humour and his style of theatre, and he seemed like a natural fit for Coulrophobia. The devising process consisted of us locked in a room attempting to make him laugh. Adam and I threw ideas at him and he would turn them on their heads. We played lots of status games, satirising traditional circus routines… John’s main task was to take the huge amount of material we came up with and hone it into a cohesive show.’

Dik has worked with puppets for decades, but mixing it up with latex masked characters – so replacing the mask with clown makeup wasn’t a big step. He also says, ‘I wanted to keep puppets within the show, but didn’t want to make a puppet show per se’. At one point, Dik gave the show the tag line ‘crap clowns do puppets’ – although LIMF’s brochure gives the rather more elegant description of ‘two clowns in search of freedom from a bewildering cardboard world.’ So why cardboard, Dik?

‘I love cardboard! My big idea was that we would ask each theatre we performed at to supply us with huge quantities of cardboard boxes and then we would arrive early with tape and a glue gun and build the set and props. Luckily that idea was too ridiculous to be feasible… We actually made the show at Nordland Visual Theatre (NVT) on the Lofoten Islands in the Arctic Circle and they had collected as much cardboard as they could find in such a remote place. I often work with a fantastic puppet maker, Emma Powell, and it was her task to make anything we asked for through the devising process, be it cardboard cowboy hats, a ship or even a cardboard chainsaw. Emma and I then built the set from large boxes for fridge-freezers and I had some boxes custom-made by a cardboard box company in Bristol. The set fits inside itself like Russian dolls. One thing I have discovered is that en-masse, cardboard is bloody heavy!’

Fleur Elise Noble: ROOMAN. Photo Bryony Jackson

Another London International Mime Festival artist with a love of the material world is Fleur Elise Noble, who brings us ROOMAN. Fleur is a true Renaissance woman – a visual artist who loves paper and film equally; a theatre-maker interested in exploring the crossroads where music, dance and physical performance meet. LIMF regulars will be familiar with Fleur’s work through 2-Dimensional Life of Her (presented in 2012). So can we expect more of the same, or something radically different?

‘ROOMAN is of a similar visual language to 2Dimensional Life of Her, however it is a little bit more sophisticated, both technically and performatively. It is bigger, faster, louder, and the set is in a constant state of transformation. I still love 2D Life of Her for its quiet, humble simplicity, but I also very much enjoy the ambition and liveliness of the ROOMAN performance.’

The new show tells the fabulously surreal story of a young woman who only finds relief from her monotonous existence when she meets a kangaroo man in her dreams – and is ultimately faced with the choice, to give up or to wake up… The ROOMAN character was apparently first encountered by Fleur in her own dreams!

It is an extraordinary multi-media (in the original sense of that term) mash-up; a cleverly weaved together tapestry of puppetry, projection, animation, dance and music which combines into something its creator describes as ‘basically, a visual-musical pop-up book extravaganza!’ How on earth did she go about creating such a rich multi-layered piece of work?

‘The projection/animation is all created over a very long period of time – about five years,’ says Fleur. ‘I map it all together in my head, on paper, and then start the process of projecting onto a miniature set. Many of the visual ideas have come to me in dreams, or in flashes of inspiration. Other ideas have come thorough a series of problem solving and happy mistakes. The live action is led by the video mapped content. The three puppeteers are constantly moving around the space bringing the surfaces to life using a complex and fast moving series of cues.’

Music is a crucial element of the production, and Fleur collaborated with Jamaican-Canadian singer and songwriter Seven Chosen (previously known as Sarah Reid) in the making of the piece:

‘Seven and I met in the Philippines – she blew me away with her beautiful music and incredible creative mind. Soon after, we brought her over to Australia to devise some of the music for ROOMAN. She became an integral part of the creative process – dissecting the story and meaning with, in, and through each moment of the work.’

Kiss & Cry Collective: Cold Blood. Photo Julien Lambert

Also using intricate sets, live physical performance and projection comes Kiss & Cry Collective, with their latest piece, Cold Blood. The show features (amongst many other visual delights): Begin the Beguine performed by two tap-dancing hands sporting silver thimbles; a tank of water agitated into a sea of flickering blue ripples by fluttering fingers; and a witty choreography for six hands enacted to Ravel’s Bolero. All of this is performed live on stage, but also seen magnified on screen, as roving cameras use live-feed video to create what is, in essence, a movie filmed and edited in real time, in front of the audience. Nothing is hidden, everything is there to see: the process and the product; the ‘making of’ and the end result.

The show is a collaboration between renowned filmmaker Jaco Van Dormael and choreographer Michèle Anne de Mey, working with writer Thomas Gunzig – the same team that created the company’s eponymous first show, Kiss & Cry (which was also presented at LIMF). Where the first show explored love – and specifically, the five loves of its female narrator (one for each finger of her beautifully expressive hand), Cold Blood takes death as its subject. Not just one death, but seven – seven strange deaths inspiring seven short stories of poignant or absurd last moments which are woven into one complete tapestry. In the company’s work, the interplay of live and mediated image is a perfect metaphor for the processes of memory: the real moment and the recorded moment in dialogue with each other.

In an interview with dance critic Donald Hutera, Gregory Grosjean (who performed in the first show, and is also one of the three dancers in Cold Blood, along with de Mey and Gabriela Iacono) says of the company’s work: ‘We create a whole world with little things, and put big meaning into these little things.’ Michèle Anne de Mey adds, ‘Some of us were coming from movies, or dance, or technology, but from the beginning everybody was together and everybody could explore the areas of the other ones.’ As for those beautifully expressive hands, de Mey plays down the skill: ‘’What we do with our hands is not really special. This is quick to learn because we are dancers who know what it is to be onstage, and the rest of the body is also onstage. But there has to be the music of playing together… Now when we are onstage, everybody is scored really precisely. To be together in the score is to be in accord with everybody.’

Collaboration is the key in this company: collaboration between artforms; collaboration between performers and technicians. Each person involved in the process brings their own skills, but is also open to experimenting with other forms. In fact, we can see that collaboration and cross-artform pollination is at the heart of all the puppetry and object theatre shows discussed here. Each, it its own distinct way, opens the theatrical tool-box to use whatever is needed in the service of the show.

London International Mime Festival has a well deserved reputation for presenting the best contemporary puppetry and object theatre from across the world. The festival’s 2020 edition brings us a superb selection of work that both embraces and usurps the traditions of the form – whatever your taste, there will be a puppetry show for you.

Featured image (top) Fleur Elise Noble: ROOMAN. Photo Bryony Jackson

London International Mime Festival 2020 runs 8 January to 2 February. For full details of all referenced shows, and to book tickets, see mimelondon.com