The team who made last year’s Buddhism: Is It Just For Losers? (whose title was one of the funniest parts) have hit comedy gold this time, with a forty-five minute shake-down of performance that leads you right up the proverbial garden path and straight into the man-shed.

It skewers all theatrical tropes and theories about what acting is, who is doing it, how to put truth on stage and what an audience will or will not believe. The ‘plot’ is about how theatre is made and the show constantly shifts both its perspective and our perception. A variation then, of ‘let’s put the show on right here!’ done with sorry masculine flourish and silly props: tiny hammers, a plastic strong-bow, some phoney recording devices and an overlarge box.

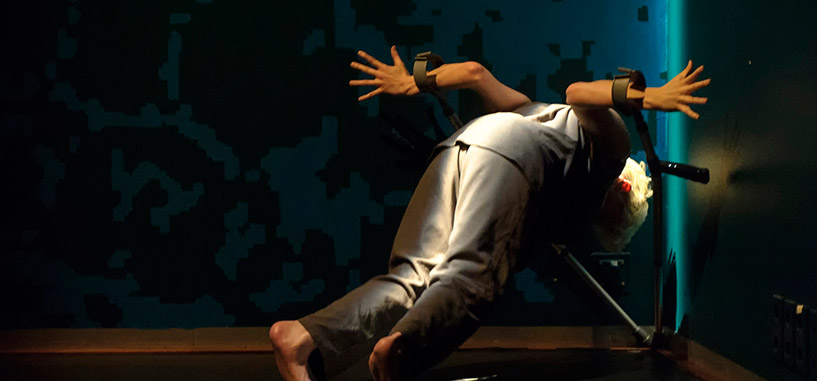

Although The Room in the Elephant lacks the visual aesthetic of Buddhism – in which the costumes and puppets were fabulous – putting the emphasis on the devising process and plot (or rather the lack of it) frees the actors up. They just have to record what they are doing ‘in the moment’ so they can do it again for real, less well. When the projected script goes blank on the screen, they are lost for words, and when Joe Mulcrone gets really angry – is he really angry or acting angry? Can his acting ever be that good? They hammer a nail into the wall, against the terms of their contract with the theatre. They are aghast to discover that their leaflets carry the show’s old title Fingers, Fists and Feelings.

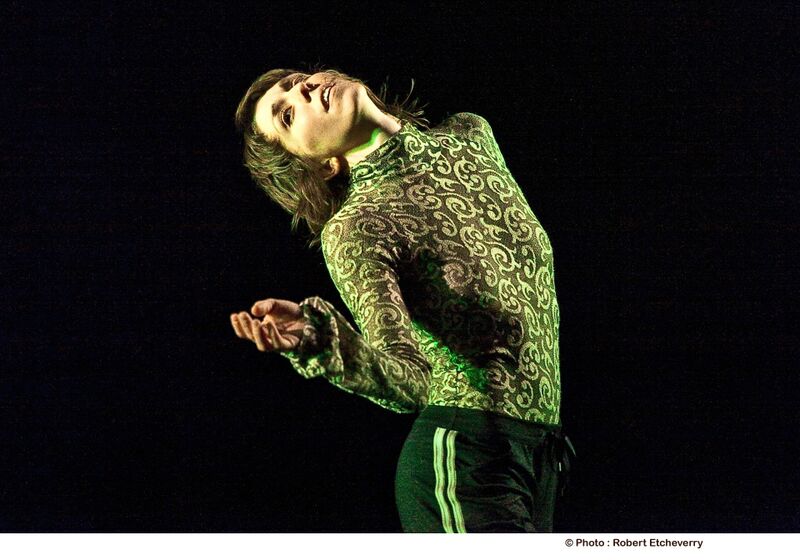

The show is credited to Inconvenient Spoof (Matt Rudkin) with Cat and Mouse Theatre (we presume the other two). There is an interesting dynamic between the three performers. Matt Rudkin was tutor to Meredith Colchester and Joe Mulcrone on the now sadly-defunct Theatre with Visual Arts course at University of Brighton, and they have made a few shows together, seeded through Matt’s regular Happy Clap Trap variety nights. Now they are on a more equal footing (or at least, this is what they are playing out onstage): creatively and financially it’s a three-way split. So Matt’s role as theatrical auteur, demanding ‘There is to be no acting, write it down, learn it and you’ll come across as wooden and shit’ is countered by Meredith’s clowning and Joe’s insistence on story and character.

Alongside the examination of meta-theatre we get shed-building, real-life enactments (Joe broke his leg two weeks ago) several visual gags, a live-art video, cod-philosophy about the sexual attraction of birds, some distracting (intended?) corpsing and a moment of discomforting manly banter.

If all this seems too self-referential and knowing for your taste, sit tight, Room In The Elephant keeps on giving and is full of surprises. The ending is total hoot. Of course the company won’t approve of my critique, as Matt made clear in the show, ‘Did you ask her for her feedback? I fucking hate that.’